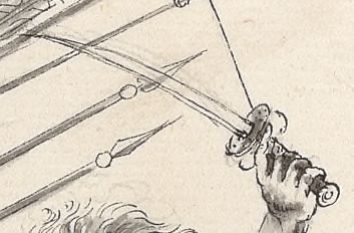

Eyewitness image of a flibustier with captured Spaniards in chains. From the French chart Carte particulière de la rivière de la Plata by Paul Cornuau, probably 1684 based on a nearly identical chart he drew of the River Plate dated 1684. (French National Library.)

EXQUEMELIN’S HEROES & THEIR CUTLASSES

Although the fusil boucanier–the long-barreled “buccaneer gun” of which more blog posts are forthcoming–was the primary weapon of the buccaneer and flibustier, the cutlass was an invariable part of their armament, which also included one or two pistols and a cartouche box (sometimes two) that often held as many as thirty cartridges each. Grenades, firepots, and boarding axes were additional specialty weapons. English/black bills were fairly common aboard English men-of-war of the era (and halberds aboard the French) as well. Some seamen (and we assume some buccaneers) carried broadswords or backswords instead of cutlasses, and English seamen were known as adepts with cudgels and handspikes (see Samuel Pepys re: the latter). In a separate post I’ll discuss broadswords, backswords, cudgels, and handspikes.

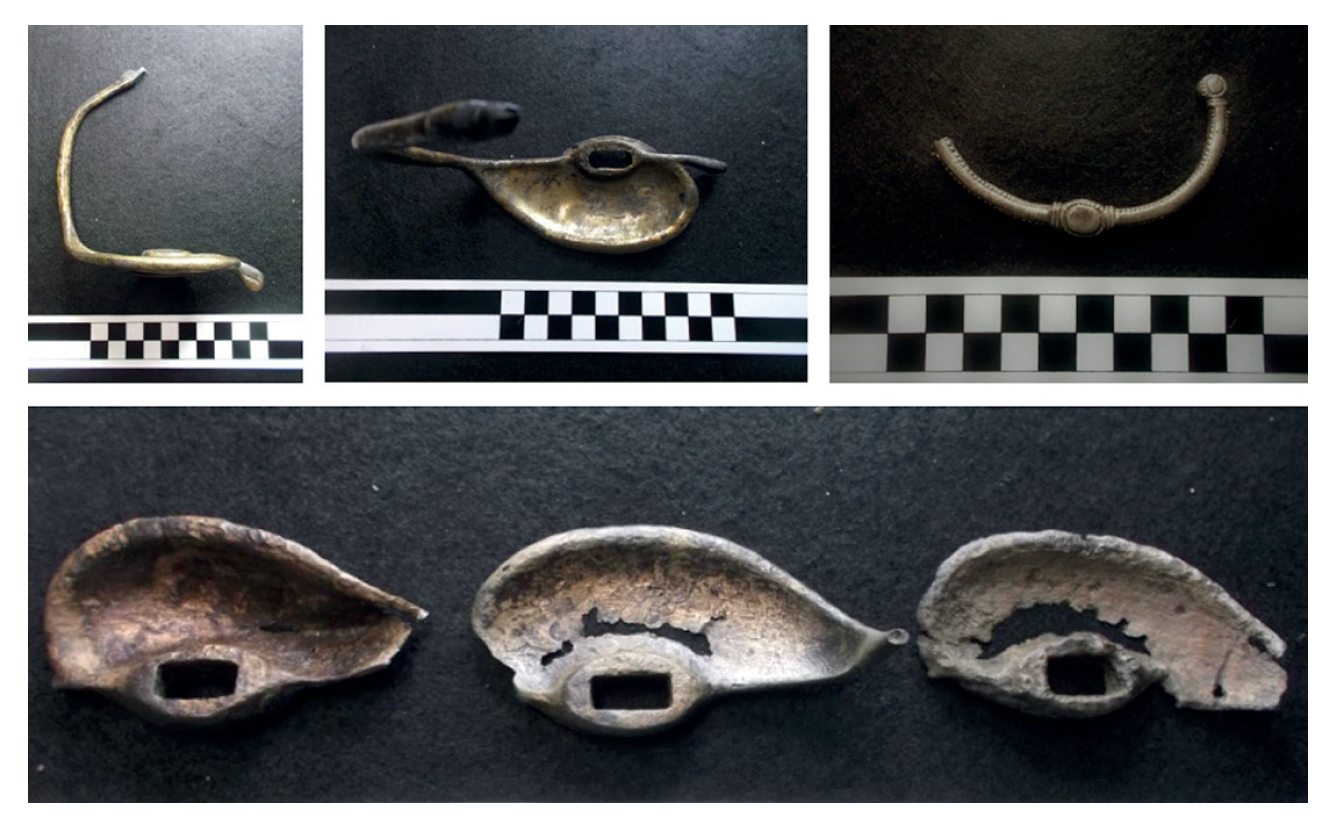

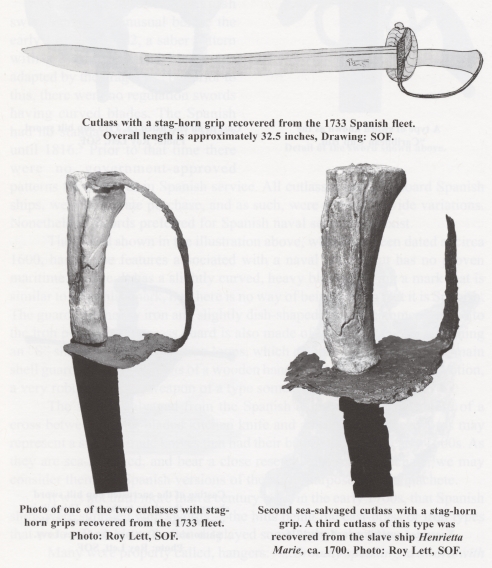

Yet in spite of all the romance of buccaneers and their swords–cutlasses usually in reality, but often rapiers in cinema–we don’t know as much about the swords themselves as we would like. Much of what we think we know is based on conjecture, and this conjecture is based on what little we know about cutlasses and hangers of the late 17th century. Unfortunately, the archaeological evidence is for all practical purposes non-existent in regard to demonstrable buccaneer swords 1655 to 1688.

Cinema, the source of much of the popular image of the pirate cutlass, almost always gets these swords wrong. Typically they are anachronistic, often imitations of nineteenth century “soup bowl” hilts (and occasionally authentic 19th century cutlasses) drawn from prop stocks. Money is always a concern in film-making, and it is much cheaper to use existing swords than to make historically accurate ones in large quantities, or, too often, even in small quantities. Good historical consulting and the willingness to follow it is, of course, mandatory, but some filmmakers take the view of “Who cares? Hardly anyone will notice, what matters is that the swords look cool or ‘Rock and Roll’ or otherwise meet audience expectations, and anyway, we don’t have the budget for accurate ones, the actors and computer graphics have consumed it all.” On occasion, though, we do see fairly accurate swords in cinema–just not very often.

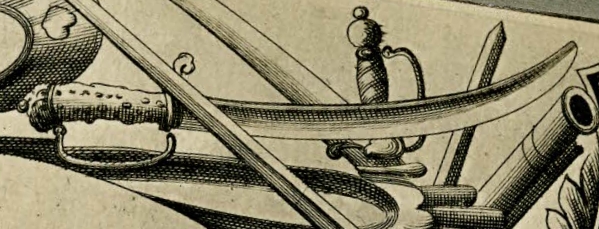

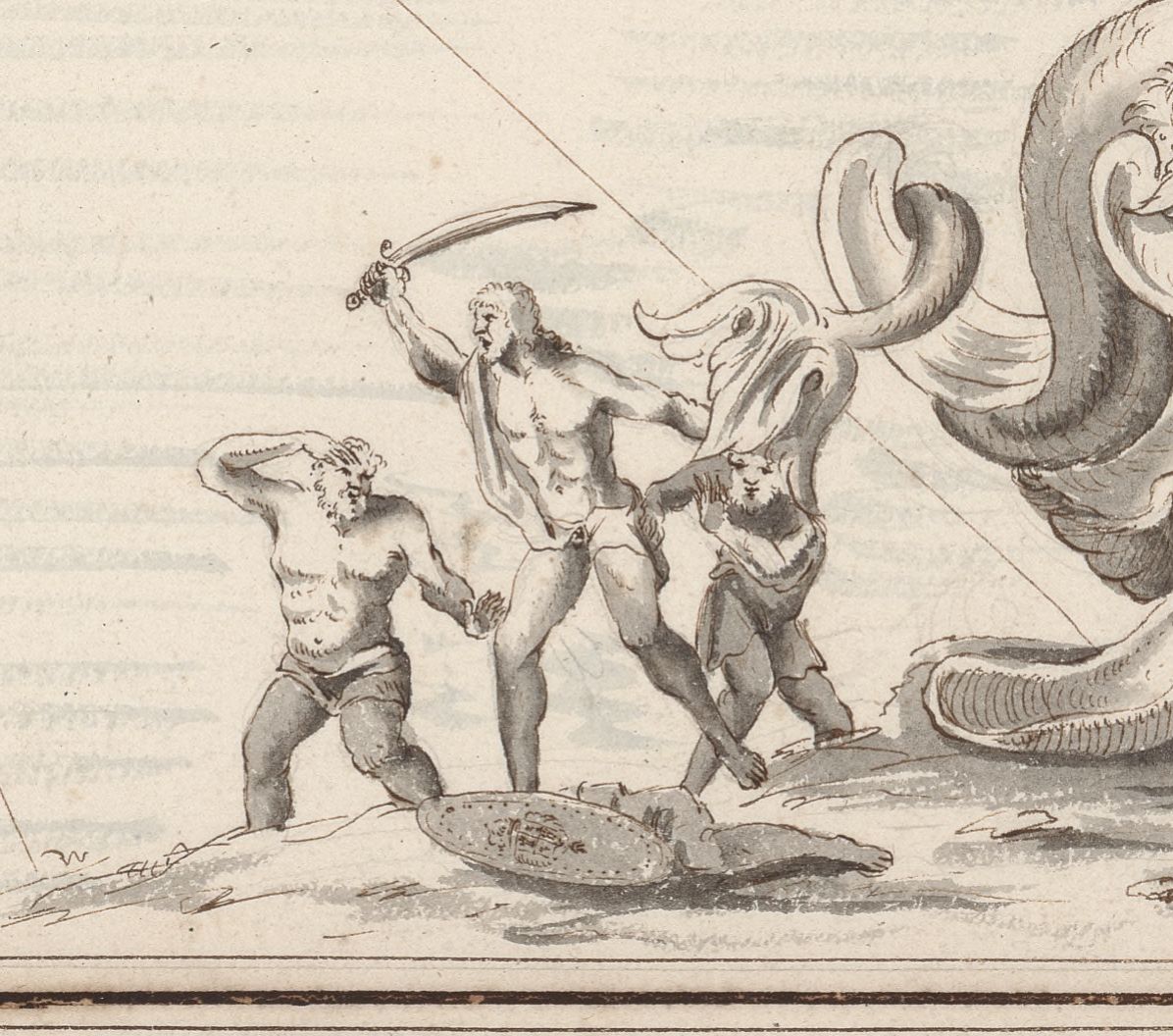

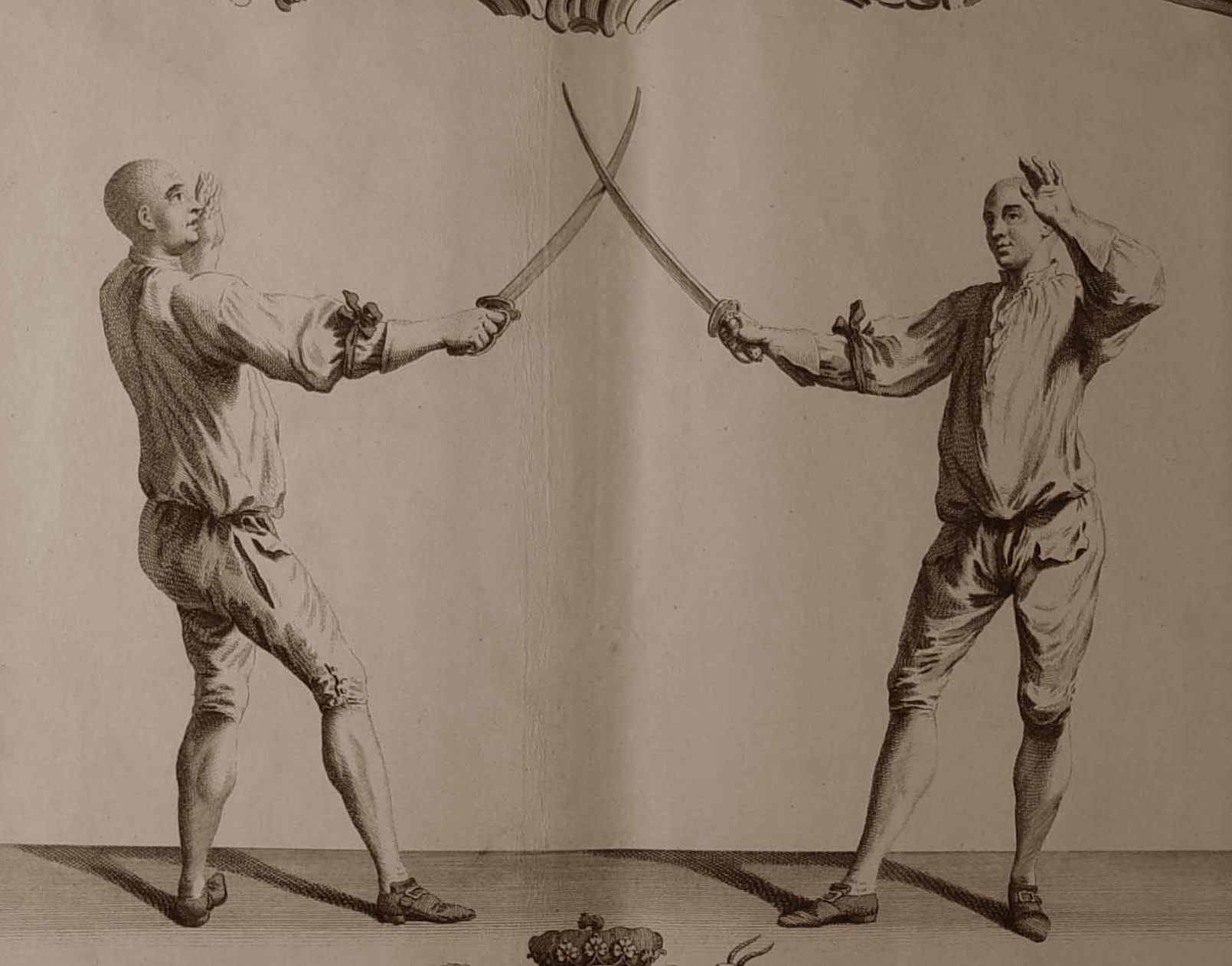

Our typical idea of a “true” pirate cutlass is taken from the illustrations, such as that above, in Alexandre Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America. First published in Amsterdam in 1678 in Dutch, the illustrations have been copied to other editions, typically with little or no alteration. Herman Padtbrugge, draftsman and engraver, may have been the illustrator according to the British Museum. It is unknown how much influence Exquemelin had on him, or on whomever was the illustrator. In other words, it is unknown how accurate the physical representations the buccaneers are, nor how accurate their arms and accoutrements. The cutlasses depicted in Exquemelin may simply reflect the illustrator’s Dutch nationality and familiarity with Dutch arms. Notably, the large seashell-like shells of the hilt do have an obvious maritime flavor, and are the perfect arme blanche with which to equip a buccaneer in an illustration.

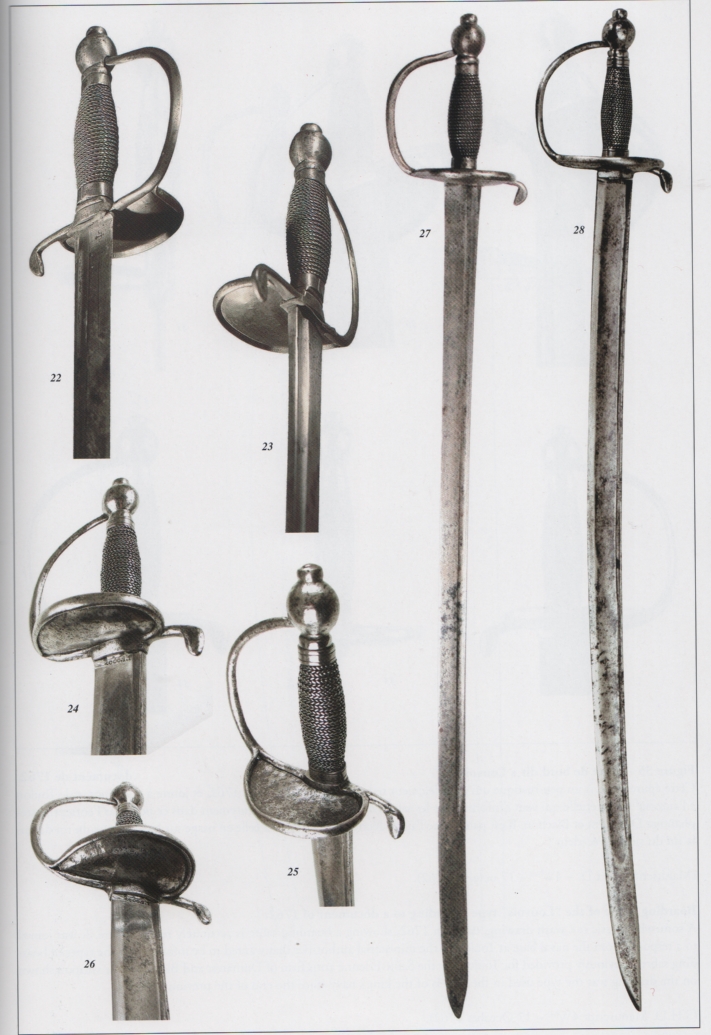

Even so, the cutlasses are accurate representations of classical late seventeenth century Dutch or German weapons with large iron shell-hilts, manufactured well into the mid-18th century with basically no design changes. Basically, these cutlasses are German-style dusacks with simplified hilts. Similar shell hilts were manufactured by other European nations, albeit typically with somewhat smaller shells. The English, for example, produced some cutlasses or hangers with somewhat smaller but similar shells during the 1660s. The Dutch and German shells are usually quite large and often scalloped, the pommels often heavy for balance, the blades mildly to strongly curved, often with clip points. (Notably, cutlasses or hangers seen in paintings of Dutch naval captains and admirals have only small shells.)

Typically these large shell-hilts may have had a single shell on the outside, with or without a thumb ring on the inside, although usually with one; or a large outside shell and smaller inside shell, both most commonly facing toward the pommel. A thumb ring may be present or absent in the case of two shells. These heavy-hilted cutlasses may have two short quillons with no knuckle bow, or a conventional short or medium upper quillon along with a lower quillon converted to a knuckle bow as in the image below. Pommel style and grip style and material–wood, bone, antler, brass, shagreen (“fish skin,” ray skin), wire over wood, or even iron–vary widely. Blade balance varies just as widely, with some heavy-bladed cutlasses balanced more like cleavers than fencing swords. This is not a criticism: cleaving strokes with a cutlass are quite effective at close range.

The cutlass wielded by Rock the Brazilian above appears, on close examination, to have a single outside scalloped shell, two quillons (although it’s possible the lower quillon might actually be a knuckle bow, but I doubt it is), a heavy pommel, and a thumb ring.

L’Ollonois above holds a typical Dutch or German scalloped shell-hilt cutlass of the late 17th century. Its shell is medium to large, the quillons small and curved, the pommel round and heavy, the blade moderately curved and with a clip point useful for thrusting. It appears it may have a thumb ring or an inner shell, probably the former.

EYEWITNESS IMAGES OF BUCCANEER & FLIBUSTIER CUTLASSES

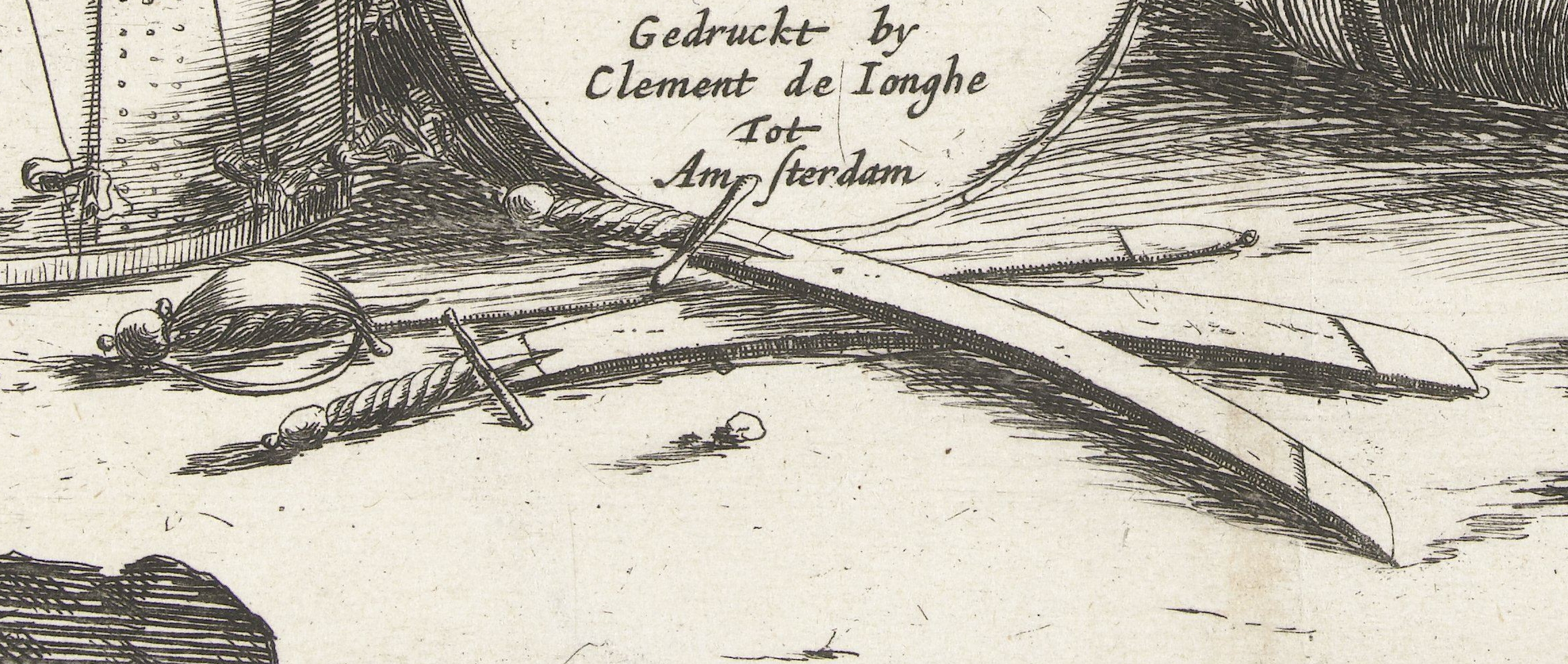

What we do not know is how common these swords were among buccaneers and flibustiers. Doubtless there at some among them, given how common these cutlasses were. However, the most direct evidence we have of the sort of cutlasses used by these adventurers comes from several drawings of flibustiers in the 1680s by Paul Cornuau, a cartographer sent to survey French Caribbean ports, in particular those of Saint-Domingue (French Hispaniola, modern Haiti). Typically he included local figures flanking his cartouches, and most of these figures are flibustiers and boucaniers. Notably, these are eyewitness illustrations! (See also the The Authentic Image of the Real Buccaneers of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini (Updated) and The Authentic Image of the Boucanier pages for other eyewitness images.)

In the image at the very top of the page, the flibustier holds a cutlass with a small hilt of indeterminate shape, without a knuckle bow, and with a strongly curved clip point blade. There is no baldric: he wears a sword belt of the sort common at the time, with a pair of hangers with loops (one of them is not shown) hanging from the belt itself. None of these period images of flibustiers show baldrics, although they were a common way of carrying a smallsword into the 1680s for civilian use, and prior to this by infantry and other military branches. However, most infantry began abandoning them in this decade, if not earlier, and they remained in use afterward primarily by mounted troops and Scottish Highlanders.

In the image above, we can tell little of the cutlass belonging to the flibustier on the left except that it has a clip point and that it may be of brass, based on its probably monster, beast, dog, or bird pommel, although some iron pommels have a similar profile, and some iron hilts have similar brass pommels. It appears to lack a knuckle bow. Its scabbard is worn from the belt. The flibustier on the right holds a cutlass with a moderately curved blade and clip point. Its hilt has two shells, both small and scalloped. Its pommel may also be of some sort of beast or bird, although we cannot be certain, and there is no knuckle bow. Again, the scabbard is worn from the belt. A similar illustration of a flibustier (on the Authentic Image post, of a flibustier at Île-à-Vache, 1686, from a chart by P. Cornuau) shows only a scabbard with an obvious clip point. It, too, is worn from the belt.

In the image above we have more detail of the hilt. It is clearly of the monster, beast, dog, or bird pommel type, almost always brass. There is a bit of shell showing, but what sort we can’t tell other than that it is scalloped, although if brass we know it is comparatively small. Again, there is no knuckle bow. Notably, the scabbard, which also has a chape (metal protection for the tip of the scabbard), does not necessarily reveal the blade form: it may be with or without a clip point.

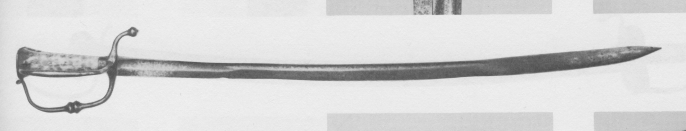

So, what would these cutlasses depicted by Cornuau actually have looked like? And what is their origin? For the latter answer, the cutlasses could be of Dutch, English, or possibly French origin. There are numerous English cutlasses and hangers of this form still extant, and of the Dutch as well; the Dutch are often credited as the likely creators of this form. There is less information, though, and few examples, of French cutlasses from this period, although the French may have produced similar arms. There are numerous examples from English and Dutch naval portraits. Most of these swords appear be gilded brass hilts. Although some flibustiers and buccaneers may have carried cutlasses with gilded hilts, most were probably simple brass or iron.

PERIOD EXAMPLES

Starting with brass-hilt cutlasses similar to most of those in the Cornuau illustrations, we see a variety of shells and pommels above, although most grips appear to brass, or possibly wire, twisted in a sharply ascending manner. Pommels include a bird of prey, lions, and one or two indeterminate forms similar to that shown in the illustration above of the flibustier armed and equipped to march against a town or city.

If we consider that this form of cutlass is likely Dutch in origin, it behooves us to look closely at one. The image above is of the hilt of the cutlass of famous Dutch admiral Michel de Ruyter. Note that it too lacks a knuckle bow.

Below are several hilts with a variety of knuckle bows. The 4th from the left looks somewhat like a transitional rapier or smallsword hilt, but it appears it may lack the usual arms of the hilt, plus the sword hangs low from the belt and at a steep angle, making it possible that it is a hanger or cutlass. The last image has a knuckle bow of chain, as if a hunting hanger, which it might well be. Again, we see dog or monster pommels, and also lion pommels.

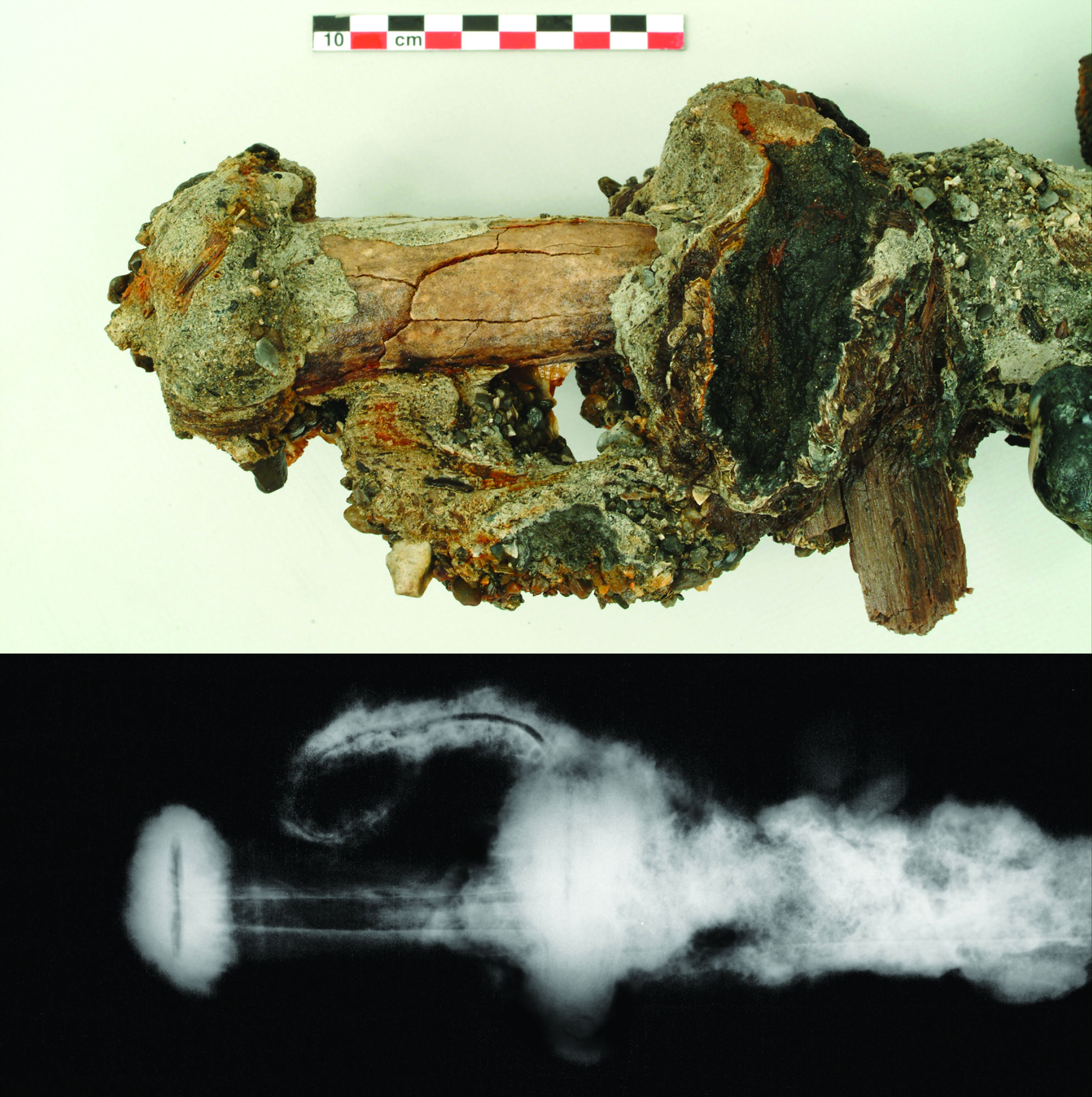

The hilt shown above may be that of a hanger or cutlass, or other cutting or cut-and-thrust sword such as a broadsword or backsword. The shells, while identical to those of a period smallsword, are, with the form of the knuckle bow, very similar to those found on some late 17th century brass-hilted English naval cutlasses. However, it is impossible to know what sort of blade was mounted in the hilt. The Elizabeth and Mary was ferrying New England militia, who were armed with a variety of non-standard arms.

Note the similarity of the sword of Sir Christopher Myngs–possibly a transitional sword with a “rapier” style blade, or a light cut-and-thrust broadsword–to that of the shipwreck hilt.

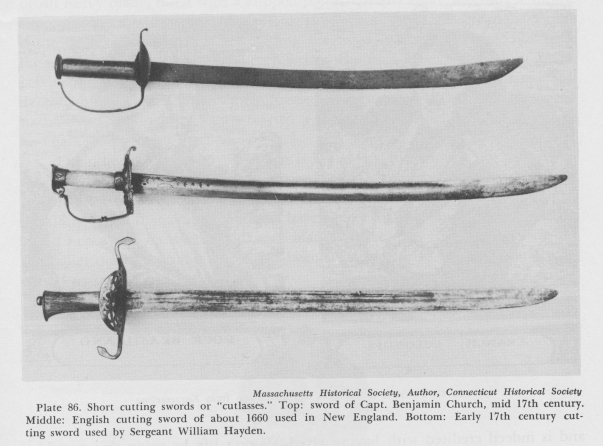

Thankfully, there remain a fair number of extant examples of hangers and cutlasses other than the few shipwreck artifacts, although maritime or naval provenance is often difficult to prove. A few examples are shown below. Note that two of them have iron shells and/or knuckle guards, with brass pommels. Some buccaneer cutlasses could have been of this form.

In addition to online sources, several good illustrations of brass-hilt cutlasses, which were typically more ornate than iron-hilted, can be found in William Gilkerson’s Boarders Away, With Steel (Lincoln, RI: Andrew Mowbray, 1991). Images of cutlasses from Harvey JS Withers’s collection for sale and sold can not only be found online, but in his book, The Sword in Britain, volume one. There are other available sources as well, including several additional reference in this blog.

Below is a detail from an illustration of the famous Jean Bart–a Flemish corsaire in French service–showing him with a cutlass. (Several other period images show him armed with a smallsword, but at least in the image below he is on the deck of a ship.) The cutlass has what appears to be a bird pommel, a small outside un-scalloped shell (or possibly a disk shell), an upper quillon, and a clip point. The hilt is probably brass, and, given its owner, might be gilded.

The illustration of Bart’s cutlass may represent a common cutlass carried by French naval and privateer officers, or it may represent Bart’s Flemish nationality. It appears to be a fairly accurate representation of a Dutch or English cutlass or hanger as discussed previously, although, if we look at the pistol in the belt, we may draw some reservations about its accuracy. The pistol, carried as many were, tucked behind the sash or belt on the right side to protect the lock and make for an easy left-handed (non-sword hand) draw, has errors: both the belt-hook and lock are shown on the left side of the weapon, for example, and the lock is inaccurately drawn. The lock should be on the right side, and the cock and battery are unrealistic. It is possible, but highly unlikely, that the pistol represents a double-barreled pistol with double locks.

OTHER CUTLASS HILT FORMS & SOURCES

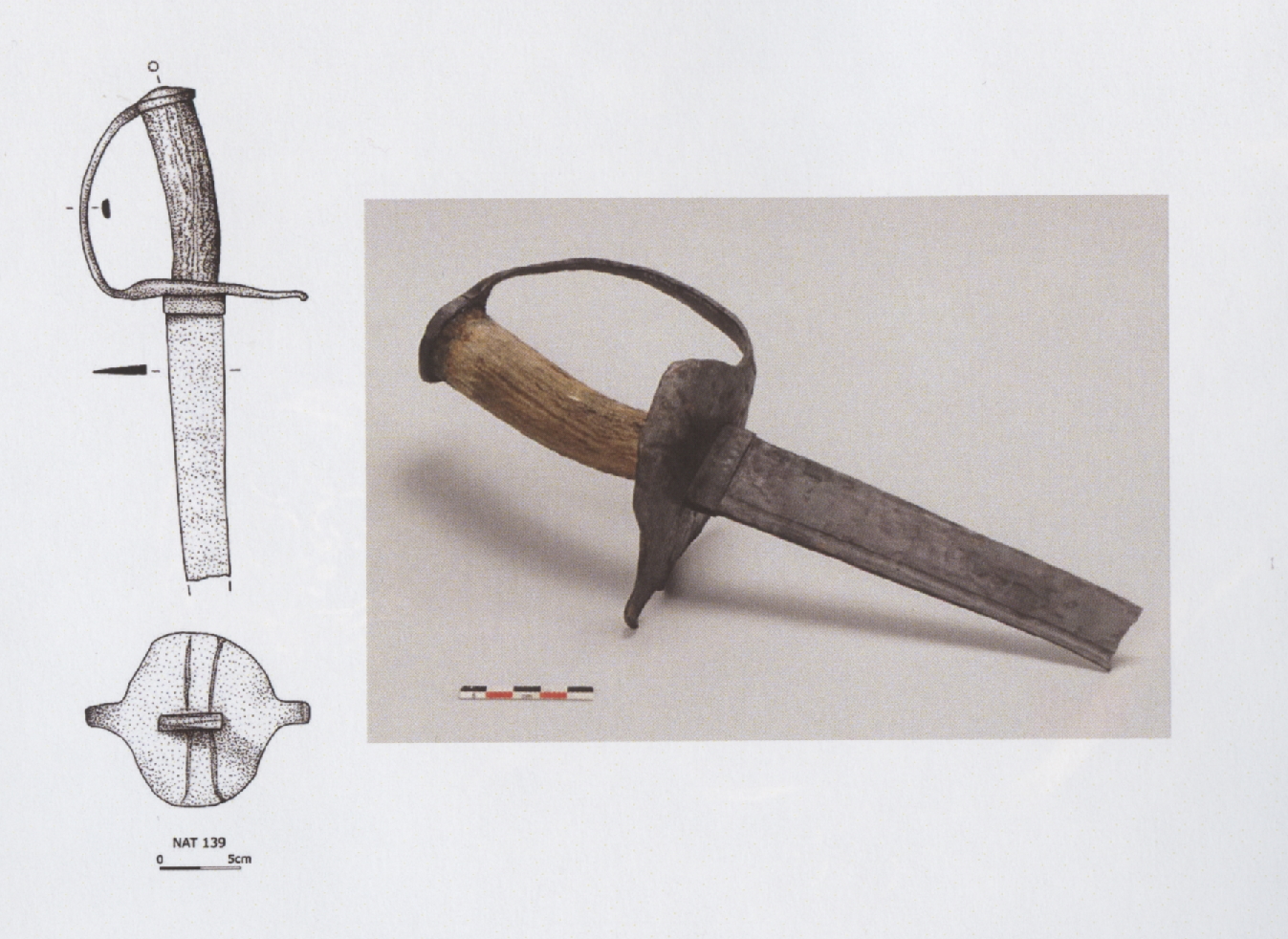

Other forms were doubtless used, including the Dutch/German discussed above, as well as the very common smaller iron shell-hilt cutlasses as in the example below. Both William Gilkerson in Boarders Away, With Steel (Lincoln, RI: Andrew Mowbray, 1991) and Michel Petard in Le Sabre d’Abordage (Nantes: Editions du Canonnier, 2006) include a fair number of illustrations of common iron-hilted 17th and early 18th century cutlasses. These cutlasses range from a simple outside shell with no thumb ring, to inside and outside shells (the inside typically smaller) with or without thumb rings. On occasion the inside shell faces forward, especially if small. Invariably either an upper and lower quillon exist, or an upper quillon and knuckle bow. Grip material varies as with the Dutch cutlass first described, although wood and bone are the most common materials.

Another common enough form with a pair of bows, one for the knuckles, the other for the back of the hand, is shown below. This form is occasionally seen combined with small shells on brass hilts as well, as in an example above.

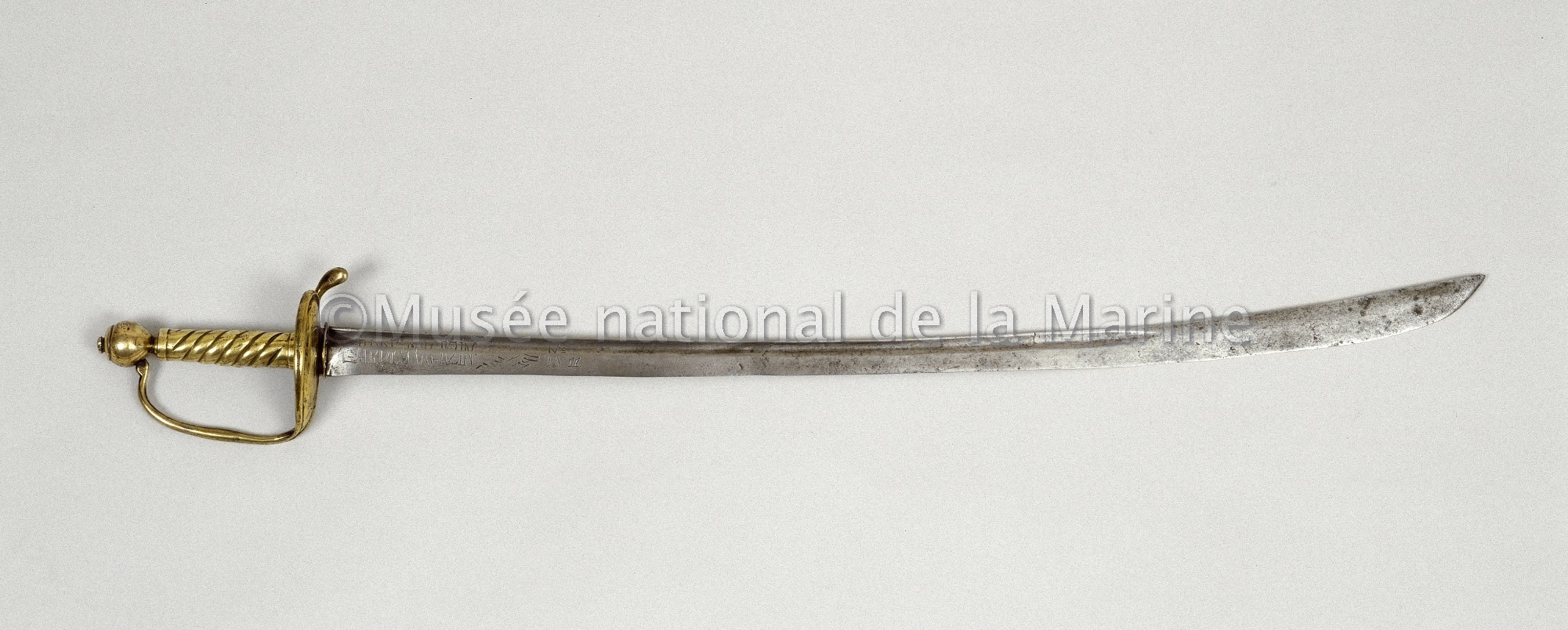

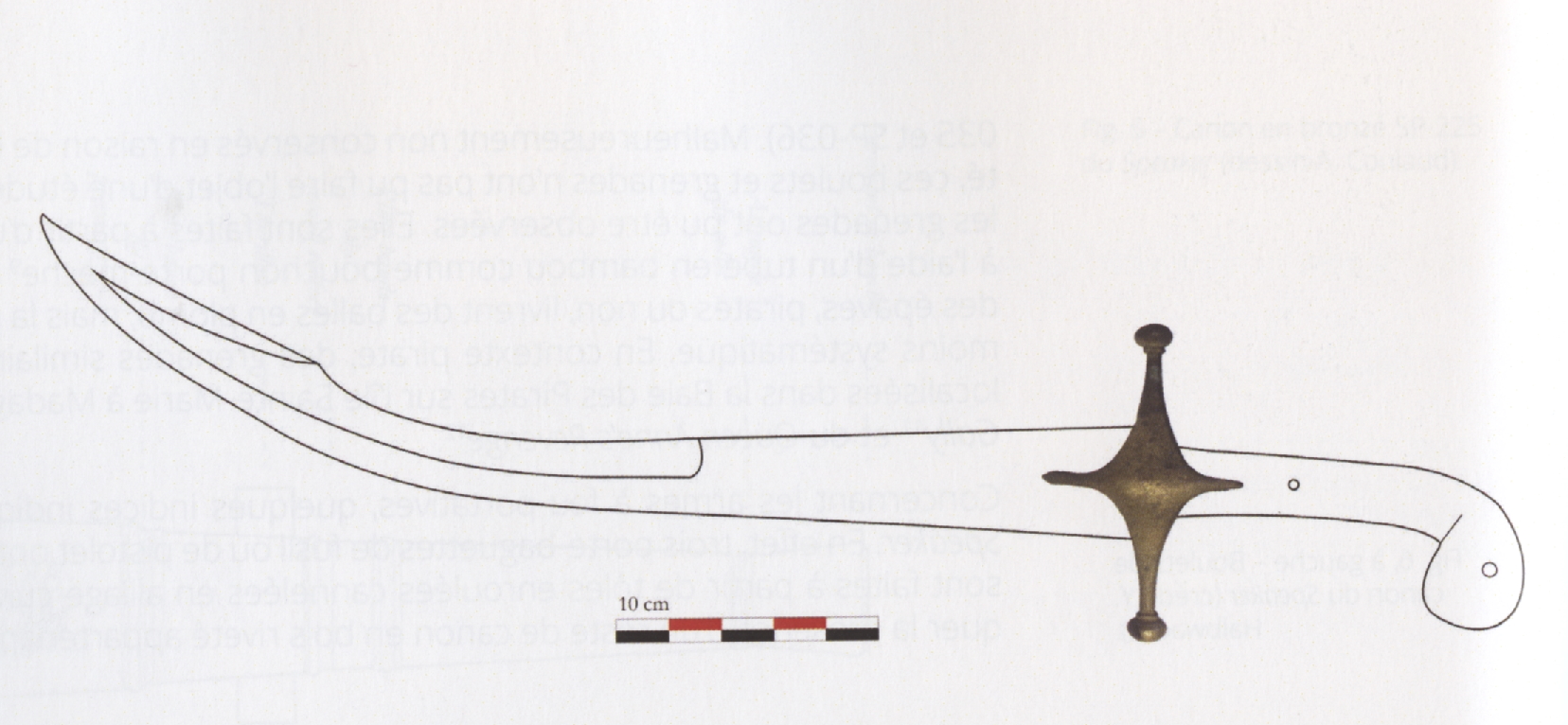

Of the late seventeenth century cutlass identified as French, Michel Petard in his excellent Le Sabre d’Abordage describes only one form, shown below. It is iron-hilted and has a single simple outside shell, a small quillon, a knuckle bow carried to an un-ornamented pommel. Almost certainly there were brass-hilted versions of this sword; the French grenadier sword of roughly the same date is identical, except in brass. It’s quite possible, even likely, that some flibustiers carried swords like these, both iron- and brass-hilt versions, but they do not appear to match those in Cornuau’s illustrations.

French paintings of admirals and other officers are typically of no help in identifying French cutlasses or hangers. Most of these portraits are highly stylized and show officers in full armor. When swords are shown at all they are typically smallswords (epees de rencontre).

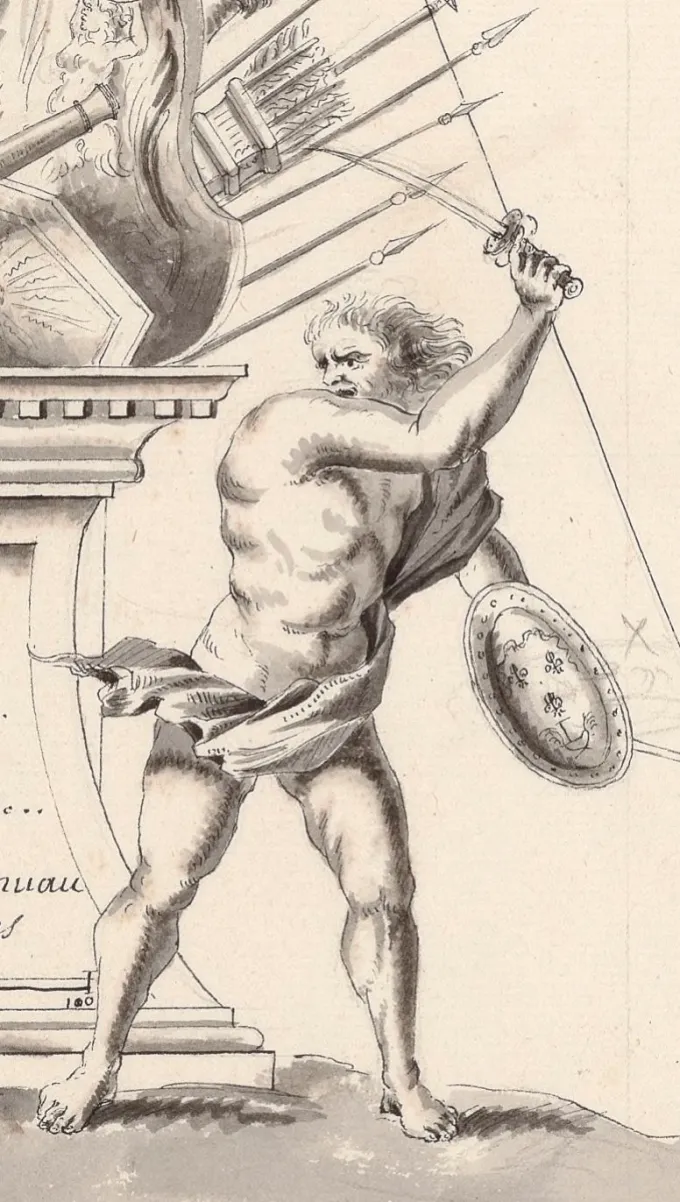

In Cornuau’s allegorical image above, perhaps of France as Neptune or Mars, the swordsman wields a cutlass of indeterminate shell construction (possibly a simple flat disk, as in the case of some 17th and 18th century hangers and cutlasses, see image below, or a crudely drawn double shell hilt), a cap pommel, and mildly curved blade with a sharp, non-clip point and a single fuller along the back of the blade. Again, it is unknown whether this cutlass is intended to portray a flibustier weapon. Similar examples from the 17th and 18th centuries are known, including a Spanish cutlass. In general, these cutlasses consist of a simple roundish shell with a small upper quillon and a knuckle bow, or of a simple roundish shell with a small upper and lower quillon forged from the same piece of iron.

The sword above is identified by the Mariner’s Museum as a 17th century Spanish naval hanger (cutlass, that is). The shell, quillon, and knuckle guard are iron, as are the plates on either side of the handle. The hilt is without doubt that of an espada ancha (wide or common sword) of New Spain from the 17th or 18th century, commonly used by rancheros and mounted troops as both a weapon and tool similar to a machete. Although most had straight blades, the curved blade of this one does not necessarily mark is as maritime, although surely some of these swords were found aboard Spanish vessels in the Caribbean, particularly those sailing from Mexican ports such as Veracruz. A lack of blade markings is common. Chamberlain and Brinkerhoff in Spanish Military Weapons in Colonial America, 1700-1821 note that swords like this are commonly seen from the late 18th to early 19th centuries. In other words, the date may be incorrect.

Another reportedly (by an auction house) 17th century Spanish cutlass above. Iron-hilted, 22″ blade. The design is similar to the previous: knuckle guard, small upper quillion, small shell or outer guard. It too appears to be an espada ancha; I’d like to know how the auction house dated it. Its date too may be incorrect.

From the first quarter of the 18th century, the Spanish cutlass hilts above were authorized in 1717. The French influence is obvious.

The allegorical image above by Cornuau, shows a man–again perhaps France depicted as Neptune or Mars–wielding a falchion or falchion-like cutlass with a simple hilt, round pommel, and curved blade with clip point. At the man’s feet lies a corpse cloven in half through the torso. It is unknown whether this cutlass is intended to portray a flibustier weapon. That said, there were similar mid- to late 17th century cutlasses and hangers, the one below for example.

Another form that may have been seen among buccaneers is that of the Eastern European short scimitar or saber, or even long as depicted below.

CUTLASS DESIGN AND USE

A few notes on the design and use of the cutlass are in order. Note that a thumb ring serves a very useful purpose in a sword with an unbalanced hilt, that is, one in which the outside shell is significantly larger than the inner, or in which the inside shell is entirely absent: it permits a stronger grip, preventing the blade from turning as a cut is made. If one’s grip is not firm when cutting with an unbalanced hilt, the blade may turn slightly and cut poorly or not at all. In cutlasses with a single large outside shell, any looseness in the grip will cause the cutlass to turn in the hand toward the heavier side.

Ideally, for a cutting blade to cut properly, a “draw” or drawing action must be made if the blade is straight or mostly straight. Some backsword and broadsword texts make obvious note of this, that the blade must be drawn toward its wielder in order to cut. (It may also be pushed away, in the 18th century this was known as a “sawing” cut.) However, the diagonal cuts from high outside to low inside, and high inside to low outside, have a natural “drawing” motion as the arm is brought toward the body. To make a powerful drawing cut is fairly easy: simply draw the elbow toward the body as the cut is made. A lightly laid on cut with a straight edge, one made with small arm movement, will require a deliberate drawing motion.

Sweeping cuts are the most common sort of drawing cuts, but they are dangerous in practice unless one is mounted (and moving quickly) on a horse, or has a shield, targe, or other defense in the unarmed hand. Sweeping cuts are easily “slipped”–avoided–and as such leave the attacker vulnerable to a counter stroke in tempo. They are also subject to counter-attacks in opposition. Tighter cuts may also be made with a natural draw, and this sort of cutting action is generally preferable when fighting without a shield or targe, as is the case in boarding actions. Note that wide sweeping cuts are more likely to injure one’s companions in a boarding action, and to get caught up in rigging and fittings.

In particular, a straight-bladed cutlass or other sword requires a drawing action in order to cut well. A curved blade has a natural cutting action, and the more curve there is the less drawing action must be added–the severe curve suffices. However, the greater the curve the less suitable for thrusting a sword is. A direct thrust made with such a sword (see the two heavily-curved examples of Tromp’s swords, for example) will result not in the tip penetrating the adversary, but with the first inch or two of the edge hitting. It is very difficult to push the edge of a sword deeply into tissue, and most wounds caused this way are superficial. Note that the clip point found on many cutlasses is designed to make a curved blade more effective at thrusting.

I am going to devote only a few words to the popular misconception that a heavily-curved sword, such as a scimitar, can be used to thrust effectively. Its true thrusts must be hooked, and the typical example one finds in discussions by self-appointed “experts” is that of a hooked (aka angular) thrust made after one’s adversary has parried quart (four, inside). In theory, the attacker can roll his hand into tierce (pronated), and slip around the parry with a hook thrust. This will only work if the attacker also has a shield or targe in his (or her) unarmed hand, or is wearing a breastplate: otherwise there is nothing to prevent the adversary’s riposte. In other words, try this with a curved cutlass, and while you may be able to make a thrust (which may or may not penetrate ribs) as an arrest or stop hit against a riposte, you will almost certainly also be on the receiving end of a powerful cut. In other words, try this at your peril in the 17th century.

I can think of only one exception to this advice: Andrew Lonergan (The Fencer’s Guide, 1777) notes that the Hussar saber, with its curved blade, has a natural cavé or angulation against quart, tierce, or prime parries (or any other parries, in fact). Notably, he’s referring to action on horseback with horses typically moving at speed–the rider, executing the natural angulation with the saber, can escape the riposte as he rides by, while simultaneously cutting or thrusting with cavé, which at speed will push not the point but the edge through neck or arm. This is much more difficult to do with a simple thrust or thrust with lunge, and, as noted lacks the protection of riding past. “The bent of their swords will afford them an unavoidable Quarte-over-the-arm, or a Cavè [sic: the wrong accent is used on cavé in the original text].” N.B. a thrust, or rather, a thrusting cut can be made with the edge at the tip, but requires great force (i.e. from horseback at a canter or gallop) and is, as Lonnergan notes, primarily effective against the soft tissue and joints of the arms and neck.

One of the most effective cuts with the cutlass is a powerful drawing cut, vertically high to low, the hand drawn down and backwards, from close quarters distance, or even when grappling if the blade is free. It is a highly effective cut: I have cut through twelve inches of brisket with it.

All this said, cleaving–non-drawing–blows can cut through skin and muscle, and even break bones. One need only to test this with a common kitchen cleaver to see the efficacy of such blows, although they are generally inferior to those made with a natural drawing action. Also, a cleaving blow, even with a dull blade, can still break bones. Getting hit on the head with a heavy cutlass would be akin to getting hit with a steel rod.

The grossly exaggerated Thomas Malthus edition of Alexandre Exquemelin’s The History of the Bucaniers (1684) notes the following of the cutlass in buccaneer hands:

“Never did the Spaniards feel better carvers of Mans-flesh; they would take off a Mans Arm at the shoulders, as ye cut off the Wing of a Capon; split a Spanish Mazard [head or skull] as exactly as a Butcher cleaves a Calf’s Head, and dissect the Thorax with more dexterity than a Hangman when he goes to take out the Heart of a Traitor.”

But this may not be much of an exaggeration. Of an English seamen put in irons aboard a Portuguese carrack circa 1669 out of fear he might help lead a mutiny, passenger Father Denis de Carli wrote:

“He was so strong, that they said he had cleft a man with his cutlass, and therefore it was feared he might do some mischief in the ship, being in that condition [drunk for three days on two bottles of brandy].”

Cutlass balance determines how well the cutlass may be wielded in terms of traditional fencing actions, and which forms of cuts work best. A heavily-balanced cutlass, with much of its weight forward around the point of percussion (that is, near the end of the blade), makes for very effective cleaving and close cutting actions, and will cut well with even crude swings. However, it is less effective for skilled fencing. A well-balanced cutlass–less point or tip heavy–is a more effective fencing sword, in that it permits quicker actions such as cut-overs, but requires a bit more training or finesse to cut well. In other words, give a cleaver to an unskilled seaman, but a better-balanced cutlass to one with reasonable skill at swordplay. All this said, a skilled “complete” swordsman or swordswoman can fence pretty damn well with anything.

Switching to a discussion of how the cutlass is held, the cutlass grip, like that of period broadswords and backswords, is a “globular” one–the thumb is not placed on the back of the grip or handle. Placing the thumb on the back of the handle, assuming there is even room (typically there is not), given the weight a cutlass and its impact against its target, may result in a sprained thumb, possibly a broken one, and at the very least the thumb being knocked from the grip, thus losing control of the weapon. The “thumb on the back of the handle” grip is suitable for lighter weapons only.

Shells are quite useful–mandatory, in my opinion–to protect the hand. A single outside shell, especially in conjunction with an upper quillon and a knuckle bow, provides merely adequate protection to the hand. The inside hand and forearm remain vulnerable to an attack or counter-attack (best made in opposition). The addition of an inner shell, typically smaller, goes far to maintain adequate protection to the hand. As already noted, inner shells were usually smaller, given that the inner part of the hand (the fingers, basically) is smaller than the outer, typically 1/3 to 2/5’s of the entire fist. Again, though, differently-sized shells, especially if the difference is significant, will unbalance the weapon, making a thumb ring useful for gripping well and preventing the edge from turning and thereby not cutting.

But perhaps the cutlass’s greatest virtue, and what would have made some of its technique unique as compared to the broadsword and saber (from which late 18th through early 20th century cutlass technique was drawn), was its utility at “handy-grips.” I’ve covered this subject elsewhere, but besides the close cleaving or drawing cut described above, pommeling would have been common, and “commanding” (seizing the adversary’s hilt or blade) and grappling would have been common as well. F. C. Grove in the introduction to Fencing (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1893) wrote: “One of us once saw a sailor of extraordinary strength seize a cutlass close to the hilt, where the edge is blunt, and break it short off.” This was an extraordinary example of a surely commonplace tactic.

There are few descriptions of the cutlass in action, but of those that exist, they are quite illustrative. Of a fight between English slavers and Africans on the Guinea Coast in 1726, William Smith wrote:

“[F]or they press’d so upon us that we were Knee deep in the Water, and one of them full of Revenge, and regardless of his Life, got out into the Water behind me, resolving to cleave my Skull with a Turkish Scimitar, which Ridley perceiving, leap’d out of the Canoe, and just came time enough to give him a BackStroke, which took the Fellow’s Wrist as Was coming down upon my Head, and cut his Hand off almost. Ridley with the violent Force of the Blow at once snap’d his Cutlass and disarm’d the Negroe, whose Scimitar falling into the Water, Ridley laid hold’of, and us’d instead of his Cutlass.”

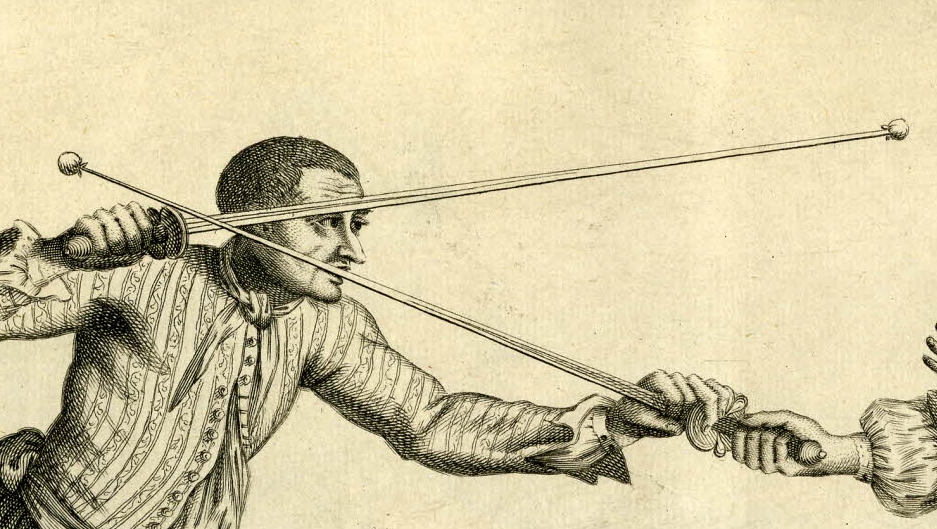

There are unfortunately no cutlass texts dating to the age of the buccaneer, and few fencing texts discuss even related weapons until the 18th century. The only 17th century exception I can think of offhand is Francesco Antonio Marcelli’s treatise on the rapier (Regole Della Scherma, 1686), in which he devotes a few pages to saber versus rapier, noting quite correctly that the saber, and therefore also falchion, cutlass, &c., is a killing weapon even at very close range. See below. In The Golden Age of Piracy I discuss to a fair degree what we know from period accounts about how the cutlass may have been used.

I’ve discussed training in the cutlass elsewhere, including a few notes in my Fencing Books For Swordsmen & Swordswomen post. In Sea Rover’s Practice I note that there was clearly some instruction at sea, although it may have often been ad hoc as was often the case ashore. Late seventeenth century French privateer captain Duguay-Trouin hired a fencing prévôt (assistant to a fencing master) to help school his crew in swordplay (and later found himself in a rencontre, swords drawn, with the man in the street), and mid-eighteenth century English privateer captain “Commodore” Walker had training sessions aboard his ship, the officers practicing with foils, the seamen with singlesticks.

The only pirate captain we know of who was said to have held swordplay practice aboard ship is John Taylor in the Indian Ocean in the early 18th century, according to prisoner Jacob de Bucquoy (Zestien Jaarige Reize Naa de Indiën, Gedaan Door Jacob de Bucquoy, 1757, page 69). Taylor’s pirate crew reportedly held practices, as Commodore Walker would later do, with foils and single-sticks. I am a bit leery of this report, however. Although it certainly may be true, it is tied to a criticism of Dutch East Indiamen captains and crews, with de Bucquoy suggesting that the pirates were more disciplined and trained in a manner that the East Indiaman crews were not. Most historical accounts show a great deal of indiscipline among pirate crews.

However, it is impossible to maintain proficiency in arms without practice, thus it is likely that pirates practiced swordplay. The question is to what degree, and whether the practice was formal or informal. Further, there is the question of whether or not pirate captains deliberately outfitted their vessels with foils and single-sticks or “cudgels” as they were commonly known. Doubtless Duguay-Trouin and Commodore Walker did, but, assuming the Taylor account is correct, Taylor’s were probably from captured stocks. That said, singlesticks are easily crafted (but not so foils). Please note that real weapons were not used for fencing practice! This would soon enough destroy their tips and edges, not to mention that it would be very dangerous even with protection. Fiction and film have, for ease of plot not to mention laziness or ignorance, given many the false idea that swordplay was practiced with real swords. A single-stick or cudgel, by the way, differs from a real sword “only that the Cudgel is nothing but a Stick; and that a little Wicker Basket, which covers the Handle of the Stick, like the Guard of a Spanish Sword, serves the Combatant, instead of defensive Arms.” (Misson’s Memoirs and Observations in His Travels Over England, 1719.)

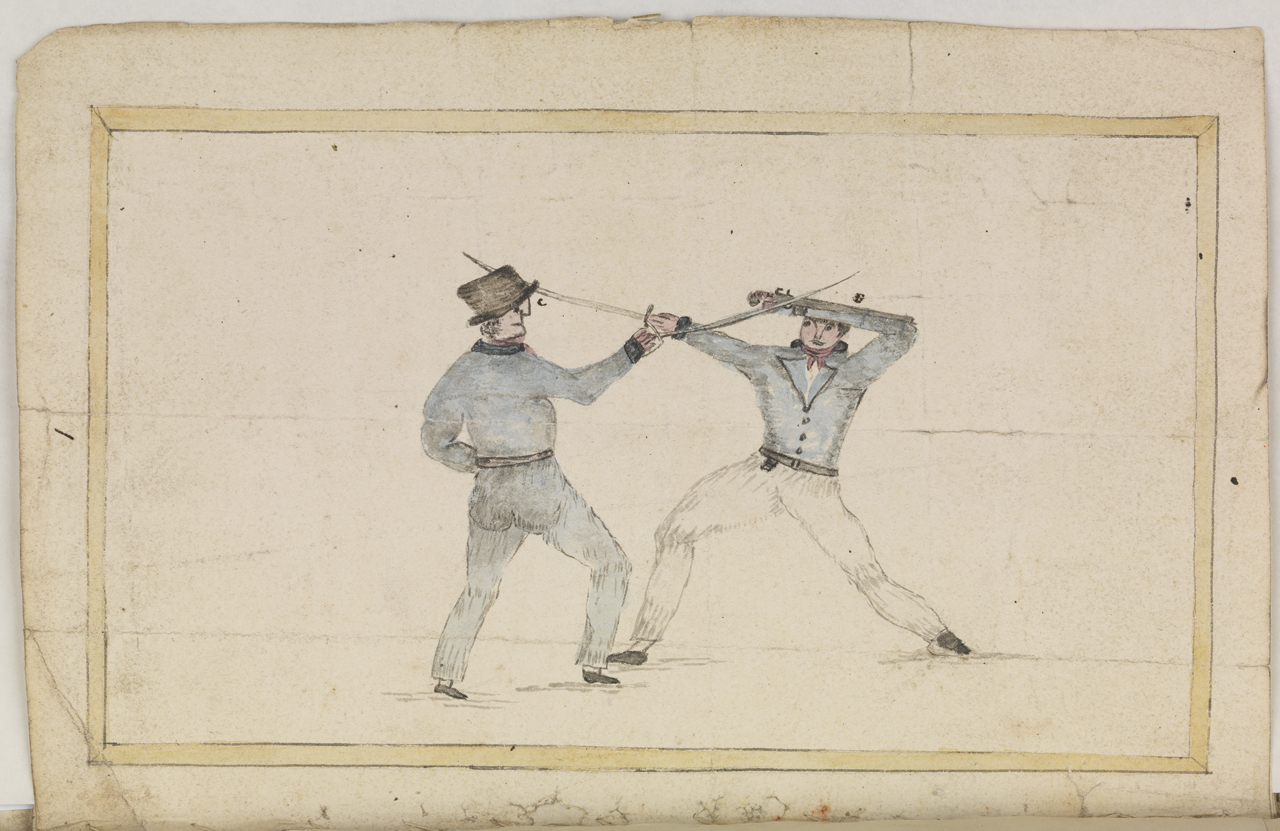

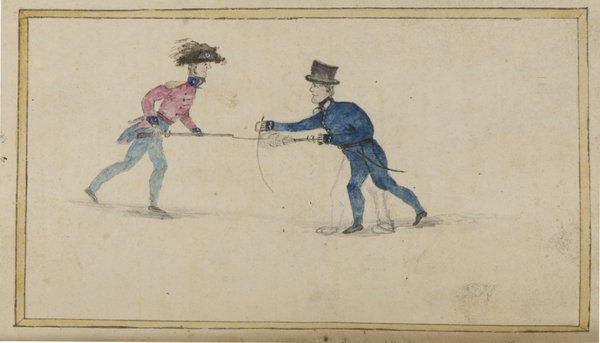

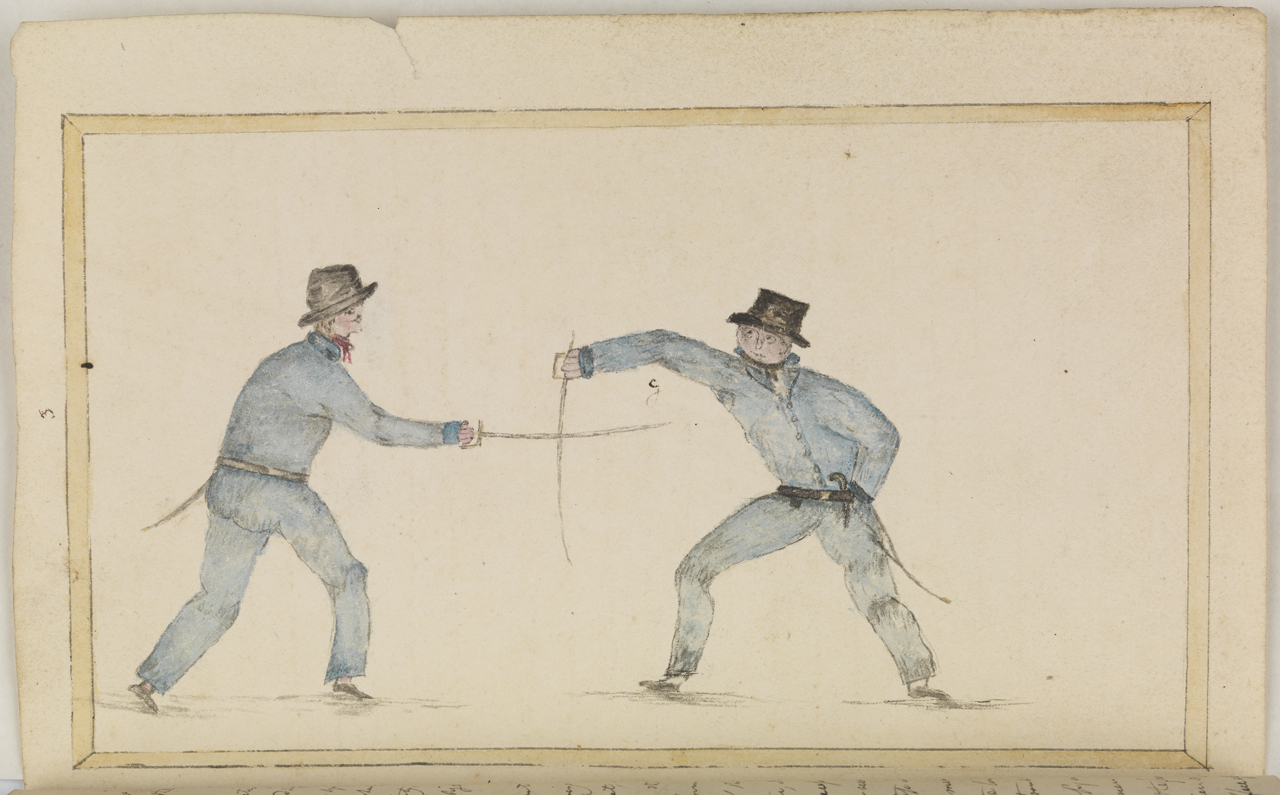

Possibly one of the more practical texts, and even then incomplete, is that of Lieutenant Pringle Green in manuscript in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. He discusses boarding actions and associated combat, with some ideas of his own. Although more than a century later than our period, there is likely a fair similarity between the two eras. See the images below.

Lieutenant Green’s text makes a few important notes. First, the seaman armed with a cutlass must know more than just protect left (inside, quarte), protect right (outside, tierce), protect head (St. George, modern saber quinte), and cut & thrust. High seconde and prime–“falloon” or hanging guards–are useful for parrying, and are mandatory to parry a musket, as he illustrates, as also half-pikes (Girard illustrated this with the smallsword in the mid-eighteenth century). The low seconde and prime parries are just as important. Second, the pistol can be used to parry when reversed along the forearm. In fact, even when holding the pistol by the grip a parry can be made, and also a forehand blow with the barrel. However, it is well to remember that Pringle Green’s text is not an exposition of hand-to-hand naval combat in actual practice, but his ideas on how it might be done better. Caveat emptor.

I’ll also point out here a rather irksome issue on occasion, that some students of historical swordplay still attempt to argue that parries with cutting swords were made with the flat rather than the edge. This is nonsense. There are some forms of swordplay, Filipino escrima and some Caribbean and Central American machete practice for example, that parry with the flat. Notably, these weapons do not have guards, and if parries are not used sparingly, and made carefully, fingers will be lost (which is almost certainly why serious sparring and actual combat with these weapons is often either in “absence of blade” and emphasizes tempo actions, or involves grappling and other manipulations in order to control the adversary’s blade). However, the forms of cutting swordplay with Western battlefield weapons–saber, broadsword, backsword, hanger, cutlass–all show the use the of the edge for parrying in texts, illustrations, and other accounts. The objection is that a parry will damage the cutting edge. And so it will. But typically the forte is used for parrying, which is seldom sharp, and even if it is, is seldom used for cutting. Moreover, those who argue for the flat rather than the edge, in spite of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, forget one thing: each time the adversary parries your blade, it will be nicked. A blade is going to get damaged in combat. In fact, there are plenty of historical accounts of swordsmen proudly noting their “saw-toothed” blades as proof of just how desperate the combat was. It is also much easier to control a heavier weapon in the parry when parrying with the edge, and more powerful parries may be made this way.

THE TERMS HANGER VERSUS CUTLASS

In regard to the myth that ‘hanger’ was the sole term used to refer to the common cutting sword at sea–to the cutlass, in other words–in the 17th century, and that ‘cutlass’ was only an eighteenth century term, I’ve excerpted the following from a Mariner’s Mirror article I wrote a few years ago (“Eyewitness Images of Buccaneers and Their Vessels,” vol. 98, no. 3, August 2012). I added it to the original draft after a pre-publication editorial reader for the journal suggested I may have used the term cutlass in error. I had to prove I was correct.

From my article: “Still debated today are the issues of whether hanger or cutlass is the more appropriate English name for the short cutting sword or swords used by late seventeenth century mariners, and whether the words refer to the same or different weapons. Hanger and cutlass (also cutlash, cutlace) are each found in English language maritime texts of the mid to late seventeenth century. In some cases there appears to be a subtle distinction made between them; in others they are used interchangeably.

“The English 1684 Malthus edition of Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America refers only to ‘cutlace’ or, more generically, sword as the buccaneer’s arme blanche. There is also at least one reference in the Calendar of State Papers, Colonial, dating to the 1680s, associating the term cutlass with Caribbean pirates.[1] The 1684 Crooke and 1699 Newborough editions of Exquemelin refer to both hanger and cutlass, and use the terms interchangeably in reference to the sword of the notorious buccaneer Jean David Nau, better known as l’Ollonais. (Hanger once, cutlass twice, as well as a note that his men were armed with cutlasses.)

“It is possible that the description of l’Ollonais’s use of his sword to mutilate and murder prisoners may have given first rise to the reputation of the cutlass as the arm of the romanticized ‘cutthroat pirate’, a reputation enhanced by Charles Johnson’s pirate history forty years later, and then by Robert Louis Stevenson and other nineteenth century novelists. Even so, the cutlass already had a sanguine reputation, doubtless inspired in part by its descriptive, alliterative name: ‘by the bloudy cut-throat cuttleaxe of swaggering Mars’ wrote Thomas Coryate in 1611. By the eighteenth century, cutlass was the predominant English term for the seaman’s short-bladed cutting sword.”[2]

In the British colonies in America, the term cutlass was often used rather than hanger in lists of militia and trade arms as well: Caribs “well armed with new French fuzees, waistbelts and cutlasses” (August 3, 1689); “100 cutlasses” (Maryland, February 4, 1706); “100 cutlaces with broad deep blades” (Maryland, June 23, 1708); “2,000 cutlasses” (South Carolina, July 8, 1715). That said, some colonies used the term hanger instead in the same period. (All citations from the Calendar of State Papers, Colonial, America and West Indies.)

The earliest Caribbean reference to cutlasses I’ve found to date is in “The Voyages of Captain William Jackson (1642-1645),” a first-hand account describing Jackson’s most famous plundering voyage from one end of the Caribbean to the other: “The Armes delivered out to each company were, Muskitts, Carbines, Fire-locks, Halfe-pikes, Swords, Cutlases, & ye like offentius weapons…” Notably the term “hangers” is not used. English naval inventories of the 17th century tend to list “hangers” and “swords” as the two sorts of swords carried aboard, sometimes listing both, sometimes only one, confusing the issue. (And no, for the occasional “expert” who wants to argue, the term hanger in naval inventories at this time refers to short cutting swords, not sword hangers.) Worse, I’ve seen “swords and cutlasses” listed among the arms of various merchantmen. Almost certainly swords other than cutlasses and, among some officers, smallswords, were commonly carried aboard ship. Certainly they were aboard Spanish men-of-war, which had a large proportion of soldiers aboard: perhaps the earliest “Bilbao hilt” cutting sword, popular in the 18th century, dates to the 1660s and was found aboard a Spanish wreck. [See Sydney B. Brinckerhoff, Spanish Military Weapons in Colonial America, 1700-1821, regarding the Bilbao hilt. Jackson’s journal was published in Camden Miscellany vol. 13, 3rd series vol. 34, 1924; the quote refers roughly to September-October 1642.]

There are plenty of other seventeenth century references to the cutlass as the predominant maritime sword or term for maritime cutting sword, as opposed to the hanger: a July 1667 report of a Dutch descent on the English coast describes the attackers carrying muskets and with cutlasses drawn; there are at least two references in the papers of Charles II to Biscayners and Dunkirkers (privateers) assaulting English merchant captains with cutlasses; the 1682 inventory of the English merchantman St. Christopher of South Carolina included “ten swords & Cutlases;” mariner Robert Everard noted a cutlass among the arms of a dying French pirate who had boarded his ship, the Bauden, in 1686 (another witness referred to it as a scimitar, a generic term for a sword with a curved blade); the 1690s broadside ballad “A Satyr on the Sea-Officers” included the line, “With Monmouth cap, and cutlace by my side…,” clearly denoting its naval use; and witnesses to the fight between the Dorrill and the pirate ship Mocha in 1697 noted that the pirates were armed with “cutlashes”; and an authority-abusing Scottish captain, part of the Scottish expedition to Darien, was described thusly: “Capt. Drummond sent his men with drawn cutlasses on board a ship, Adventure, John Howell, master, and bade deponent, who was piloting her, to anchor her under the guns of his ship.” In the Deposition of William Fletcher, May 2, 1700, the said ship master described being his beating by pirates “with the flat of the Curtle-axes.” See also the endnotes below for other seventeenth century cutlass references associated with pirates and sea rovers.

It is quite possible that the distinction between cutlass and hanger was originally determined by the blades: a broad bladed weapon with a short blade length used by soldiers and seamen was originally defined as a “curtle-axe” (Shakespeare even uses the word) or cutlass, while one with a narrower blade was a hanger. Cutting blades heavy “at the tip” are excellent for cleaving cuts even at close distance: anyone who’s used a cutlass with such a blade for cutting practice will recognize this immediately, as will anyone who’s used a Filipino bolo knife. I’m speculating, of course, but the cutlass may have found preference at sea due to its greater ability at close quarters. Clearly, swords by both names were used, but the name cutlass stuck perhaps due to its greater efficacy.

This theory of cutlass versus hanger is supported by the French definition of coutelas from the 1694 edition of Le Dictionnaire de l’Académie française: “Coutelas. s. m. Sorte d’ espée courte & large, qui ne tranche que d’ un costé. Coutelas bien tranchant. coutelas de Damas. un coup de coutelas. il luy a fendu la teste de son coutelas, avec son coutelas.” That is, a kind of sword with a short wide blade, which cuts only one side. A 1708 Maryland arms list notes “100 cutlaces with broad deep blades” (cited above), suggesting that the term had become associated more broadly with short cutting swords in general.

Further, to those who still insist that “hanger” was the more common word, note that the 1678 English translation of Louis de Gaya’s treatise of arms does not translate “coûteau de chasse” as “hunting hanger” but as “hunting cutlass.”

It bears repeating that longer swords were often carried in addition to cutlasses, given that we find accounts of “cutlasses and swords” and “hangers and swords” in ship inventories (although the occasional ignorant Internet pedant, more often than not a re-enactor) will attempt to assert that the term hangers refers only to sword-belts.

An associated trivium is in order: the French term hassegaye (from Old French azagaie, Arabic az-zaġāyah, etc.) derives from an old word meaning “short spear,” and in the nineteenth century meant a short boarding pike. However, in the late seventeenth century it’s described as the word for the cutlass a ship’s captain wielded in action by holding it aloft, usually to inspire the crew as well as to intimidate the enemy. By waving it, the captain was demanding surrender, that is, ordering enemy colors and topsails “amain”–lowered, that is. “C’est un coutelas que le Capitaine tient en la main au bras retroussé pendent le combat.”

In any case, I leave you with a quote from a witness to de Ruyter’s raid on Barbados in 1665: “I did see him [de Ruyter] on the poope, with a cane in one hand, and a cuttle axe in the other, and as he stayed [tacked] I did see most part of his quarter carried away.” The cutlass may even have been the one whose hilt is depicted above. [From “A True Relacion of the Fight at the Barbados Between the Fort and Shipping There…,” in Colonising Expeditions to the West Indies and Guiana, 1623–1667,” edited by V. T Harlow (London: Hakluty Society, 1925). The “cane” was almost certainly de Ruyter’s long admiral’s baton.

MORE INFORMATION

For more information on the use of the cutlass at sea and ashore 1655 to 1725, in particular on its effectiveness as well as on its use in dueling, see The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth About Pirate Myths, chapter 8. (My publisher won’t appreciate my repeating the information here; by agreement I am not supposed to.) Both The Sea Rover’s Practice and The Buccaneer’s Realm also include information on the cutlass and other swords; the latter has an entire chapter devoted to associated late 17th century swords and swordplay. In sum, there’s a bit more information. For example, Bras de Fer missing his Spanish adversary and cutting through his hat instead, then tripping over a root as he attempted to renew his attack; the possibility of techniques similar to those used with the dusack (e.g. grazing and yielding actions in a single tempo); &c.

That said, I will add a note to dueling here even though far more information is in The Golden Age of Piracy (including the only confirmed description of a duel fought between buccaneer captains). Although it’s unlikely that duels were regularly, or even occasionally, fought aboard ships, for reasons and evidence discussed in The Golden Age of Piracy, it doesn’t mean there weren’t occasional affrays with swords aboard ship. Peter Drake, an Irish officer, one of the so-called “Wild Geese” who left Ireland after the defeat of James II, describes how in 1701, as he joined a Dutch regiment in Dublin and waited aboard a Dutch ship to sail to the Netherlands, “Among the recruits we had two prize-fighters, who, getting drunk, fell to quarrelling; the company declaring, each for the one whose cause he espoused, an uproar ensued, and several strokes were exchanged.” But this was a brawl more than anything else, and among soldiers, not seamen. Note that prize-fighters fought primarily with various swords, as well as with quarterstaff, and occasionally with fists. (Peter Drake, The Memoirs of Peter Drake [Dublin: S. Powell for the Author, 1755]. Stanford University reprinted the memoirs in 1960, edited by Paul Jordan-Smith.)

SUGGESTIONS ON PURCHASING REPLICA BUCCANEER CUTLASSES

If for whatever reason — historical research, reenactment, swashbuckling flair for your wall, modern piracy — you want a reasonably historically accurate cutlass replica, you’re sadly and mostly-but-not-entirely out of luck. There are only a handful of sword-makers who forge what can be termed historically accurate functional cutlasses, and they’re typically priced at US$500 to $1000 or more. Few typically have stock on hand; most are commissioned orders that may take months or years for delivery. Loyalist Arms stocks a small variety of cutlasses suitable to the era. Likewise, At the Royal Sword periodically stocks a few mostly historically-accurate cutlass and hanger replicas suitable to the buccaneer and early 18th century pirate eras. Cold Steel has a hunting hanger and a “pirate” cutlass (the latter is a recent release and somewhat difficult to find as of December 2022) that are suitable, if not as accurate as might be desired. In particular, the “pirate” cutlass is more of a dusack; removing the side rings would make it more appropriate to the buccaneer era. Even so, it is something of an homage to the shell hilt cutlasses of reality and Hollywood, a “sea beast” of a cutlass, yet with beautiful balance, as might have been carried — we imagine — by Alexandre Bras de Fer, “Rocky” the Brazilian, or the infamous l’Ollonois. It and the hunting hanger with small shell are quite functional and nice pieces for the price. Note that most cutlass replicas on the market are historically inaccurate, anachronistic, or pure fantasy (some have elements of all three); many are wall-hanger junk that could not be used for actual combat.

NOTES

[1] CSPC, 1681-1685, no. 1509. January 19, 1684. “A Relation of the capture of Providence by the Spaniards. On Saturday, 19th January, about 3 o’clock, Juan de Larco with two hundred and fifty Spaniards came down the harbour and landed at Captain Clarke’s, half a mile to east of Charlestown. Captain Clarke being out of doors near the waterside, some men in ambush shot him through the thigh and cut his arms with a cutlass, and then they marched away with all haste to the town, firing into some houses as they went…”

Another instance described in CSPC, 1677-1680, no. 1624. December 30, 1680, deposition of Robert Oxe.”The Spaniards killed two men and cruelly treated the deponent, hanging him up at the fore braces several times, beating him with their cutlasses, and striking him in the face after an inhuman cruel manner.” The Spanish pirate hunters were commanded by Captain Don Felipe de la Barrera y Villegas. Under his command were Juan Corso and Pedro de Castro, two captains noted for their reprisal cruelty against English and French seamen.

[2] Thomas Coryate, ‘Laugh and be Fat’ in Coryat’s Crudities (reprint London, 1776), vol. 3:n.p. Regarding foreign terms for cutlass, the original Dutch edition of Exquemelin’s work (1678) uses sabel (saber), as does David van der Sterre’s 1691 biography of Caribbean sea rover Jan Erasmus Reyning, but a 1675 English-Dutch dictionary notes kort geweer as the Dutch term for cutlass. Exquemelin’s Spanish edition (1681) uses ‘alfange’ (alfanje), whose root is the Andalusian Arabic alẖánǧar or alẖánǧal, from the Arabic ẖanǧar, a dagger or short sword, which some scholars have suggested is the origin of the English word hanger. The OED (2nd ed.) doubts this and derives it instead from the Dutch hangher. Although the Spanish connection to the Low Countries, and thus a connection to the Dutch term, appears suggestive, the English use of hanger predates Spanish rule. Alfanje is typically translated as cutlass, hanger, or scimitar. Exquemelin’s French editions (1686, 1688, 1699) refer to both coutelas and sabre, noting that flibustiers were armed in one instance with a good coutelas, in another a coutelas or sabre. Labat, describing the early flibustiers, notes each having a well-tempered coutelas among their arms. Most etymologists consider cutlass to be derived from coutelas. Saber, sabre, and the Dutch sabel derive from the German sabel, with authorities noting the term’s Slavic origin.

Regarding the various spellings of cutlass in the mid-seventeenth to early eighteenth centuries: cutlass, cutlace, cutlash, curtlass, curtelass, courtlass, courtelass, and curtle-axe are all common.

Copyright Benerson Little 2016-2018. Originally published December 31, 2016, last updated June 6, 2023.

[…] Besides the study of backsword, broadsword, and saber texts, I recommend those of the dusack as well. Practice with a knowledgeable partner is also required, as is cutting practice in order to get a good feel for the weapon. The very few texts below are merely representative of saber technique of the later period: it is by no means a complete list. I have described late 17th century cutlass technique, or at least what we know of it, in The Sea Rover’s Practice, The Buccaneer’s Realm, and The Golden Age of Piracy, especially in the last book. Additionally, those interested may want to review my blog post, Buccaneer Cutlasses: What We Know. […]

LikeLike

My spouse and I stumbled over here coming from a different website and thought I may as well check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to checking out your web page for a second time.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

I actually practice fencing with falchion-bladed cutlasses. One type of sword I like is the 17th century walloon hilt saber, which I plan to get one of for fencing practice. I believe that it was a design that may have been less common of naval or pirate use, but would have been effective nonetheless.

LikeLike

That’s actually an area I’ve been looking into–shipboard swords other than cutlasses (or “hangers”). There are records of “swords and hangers” and “swords and cutlasses” circa 1660 to 1700 among shipboard armaments, suggesting that at least some swords weren’t cutlasses. The Walloon hilt or style is a likely candidate. There are occasional mentions of backswords and broadswords aboard ship, although in the minority. Although a cutlass with its shorter blade is ideal, there are records of longer armes blanches aboard ship: not only half-pikes (and aboard larger men of war, 3/4 and sometimes full pikes as well) and muskets with plug bayonets, but also a fair number of English bills (brown bills, black bills) and, aboard French men of war, partisans. Why not a few longer swords as well? Occasionally someone will try to argue that “hangers” in “swords and hangers” means frogs or scabbards and belts, but the term hanger was commonly used in the English navy to indicate a short cutting sword at the time, plus the numbers don’t add up (too few swords if hanger means a sword belt), plus it doesn’t account for instances of “Swords and cutlasses.” At any rate, I agree: a Walloon saber/backsword/broadsword, or a shearing sword (probably Walloon-hilted or similar?) would be a good choice even aboard ship, although a cutlass remains the ideal sword overall.

LikeLike

[…] or stab and thrust, which Lewis Carroll turned into the snicker-snak of the vorpal sword. (See Buccaneer Cutlasses: What We Know for more information on cutlasses, including a bit on […]

LikeLike

Good afternoon, I am the Editor of the Heritage Arms Magazine Barrels and Blades and would like your permission to reprint this article in our magazine. My email is heritage.arms.society@gmail.com Below are member links to our last three issues:

2022

Jan https://drive.google.com/file/d/1d0ljUd2nzg9JhNuSTxyVtxNPtxe3Xlv7/view?usp=sharing

2021

Dec https://drive.google.com/file/d/1aHf6IRje2QYpCxM_S4hyvgNldyh2Sugr/view?usp=sharing

Nov https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Fuw0CJt9XxRp3YlQwF5DSgiwgmMBEYIZ/view?usp=sharing

Kind Regards Cathey Brimage

LikeLike

I’ll email you shortly. 🙂

LikeLike