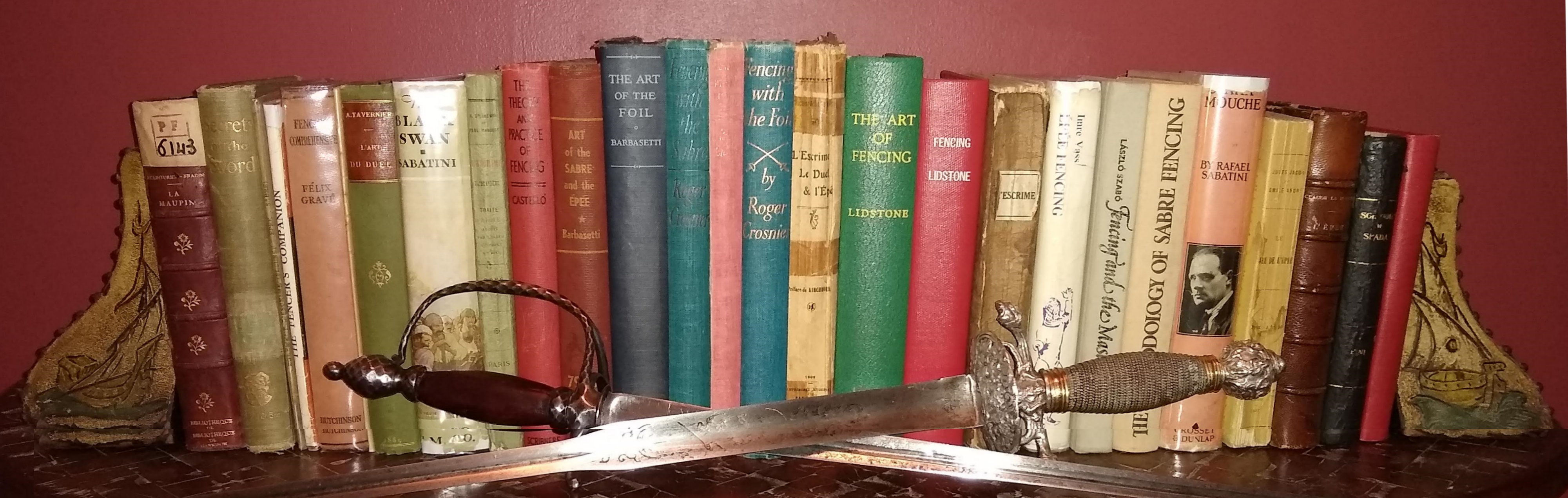

The content in this post is more background on than digression from the general subjects of this blog–swordplay and swashbucklers–, for what is either without fencing technique? The following fencing books are my recommendations for fencers across the spectrum, from early modern historical to “classical” to modern “Olympic” competitive. It includes sections on the modern Olympic weapons, classical fencing, rapier, smallsword, various cut & thrust, theory, Japanese texts, and more.

The list below, although quite long, is not exhaustive—there are many good fencing books not listed (and some more bad than good as well). Some are not listed simply because I have not yet read them. The history list in particular is abridged due to sheer volume, but less so than in past years, and I have not yet begun to include much in the way of mid-19th century works or of books on swords as opposed to swordplay. Fencing books can be very useful, but are no substitute for proper instruction and diligent practice, as I learned from my fencing masters, Dr. Francis Zold and Dr. Eugene Hamori. See the end of the list for suggestions on acquiring the books listed here, or for that matter, many books in general.

The first fencing book I ever read, in 1975 or 1976, was Bob Anderson’s All About Fencing, along with a beginning text by Nancy Curry or Muriel Bower, I can’t recall which, probably the former. These were followed by, once I started fencing in 1977 under Dr. Zold at USC, either Curry or Bower’s book (the latter I think, given Bower’s association with USC), then Charles Selberg’s Foil (and when it was published, his Revised Foil), Michel Alaux’s Modern Fencing, Marvin Nelson’s Winning Fencing, and, in 1980, Imre Vass’s Epee Fencing, soon followed by Szabo’s Fencing and the Master. From that point my interest in fencing texts exploded.

My earliest years of fencing education, however, were dominated by fencing lessons, verbal instruction, and oral histories, not fencing books. Notably, my epee instruction was derived in large part from Vass via Dr. Hamori’s own knowledge of the weapon and in consultation with his friend József Sakovits who was one of the world’s greatest epeeists and later Hungarian national coach. The general method of instruction used by my masters was derived directly from Szabo, his master Italo Santelli, and other notable Hungarian masters such as Gyorgi Piller–yet never for four years were the works of Vass or Szabo recommended to me. They were, in essence, above my ability at the time.

As Italo Santelli put it, fencing is something you do, not something you write (and therefore read) about! Thus were my early years filled with learning to fence not by reading but by fencing, fencing, and more fencing. That said, the study of fencing texts does have an important place in learning to fence: it broadens one’s knowledge of the subject. Fencing books provide a map to the world of swordplay. They can also point out errors in technique, training, and tactics (although a fencing master is always better for this), and can reorient one’s perspective in certain cases.

Associated fencing quotations can be found here.

Essays on Fencing & Life

So rare are these essays that I’ve found only one to list so far, although occasionally the subject is touched upon in prefaces to fencing books. Arguably, Bazancourt’s Secrets of the Sword and Burton’s The Sentiment of the Sword occasionally connect fencing to life in general, and Gravé’s Fencing Comprehensive has a sense of this as well. All three are noted below.

L’Escrimeuse by Emma Lambotte, 1937. A delightful essay on fencing, on being a woman fencer, on fencing’s connection to and reflection of life, and on the characters of various fencing nationalities, among many other brief subjects. Mme. Lambotte was a noted Belgian poet and the muse and patron of painter James Ensor.

Modern Epee

Why have I placed Modern Epee—that is, epee as fenced from the 1930s to the present in its various forms—first among books on technique? Because it’s the best starting point for most budding fencers today, even if their ultimate goal is classical or historical fencing. It is by far the most popular modern competitive weapon (it looks like swordplay, its judging is simple, it much more resembles sword-fighting with sharps than either modern foil or saber, it is very “democratic” in that the weaker fencer always stands a chance, as some have put it), and—if taught appropriately via a classical foundation as it should be—is an excellent foundation for historical and classical fencing. Modern competitive foil and saber have become largely useless for this, both as fenced and as taught, for they’ve given up the classical notion derived from combat that attacks in invitation–with the point non-threatening and the arm not extended or extending–would be suicidal with real weapons.

It should be noted that some modern epeeists consider not only classical epee technique (point d’arrêt technique, especially non-electrical, and true dueling technique), but also “modern classical” (electrical pre-Harmenberg, so to speak) technique to be obsolete. This narrow view has no basis in fact except to some degree in the case of some elite (world class, that is) epeeists. Purely classical and modern classical epeeists can, and often do, fence as far as a solid A, or national, level, and classical technique is the foundation of elite epee technique. In fact, elite women’s epee retains a significant amount of so-called classical technique, and the compiler of this list is well-acquainted with a Greek-American epeeist some 70-plus years old whose classical, very old school straight arm dueling technique can still give even young elite epeeists fits.

Note, however, that the definition of classical fencing has changed over time and continues to change today. More than a century ago foil was considered the classical school and epee the modern, and French duellists of a century ago were classified according to three schools: foil, foil-epee, and epee! In fact, one need only read Achille Edom’s 1910 book on epee fencing (see below) to realize that much of what is considered new in epee is in fact more than a century old. In other words, epeeists should not consider older epee texts, nor any epee style of the past century or more, as unworthy of practical study, modern fads, to which epee is highly susceptible, notwithstanding.

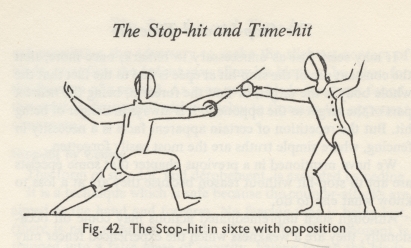

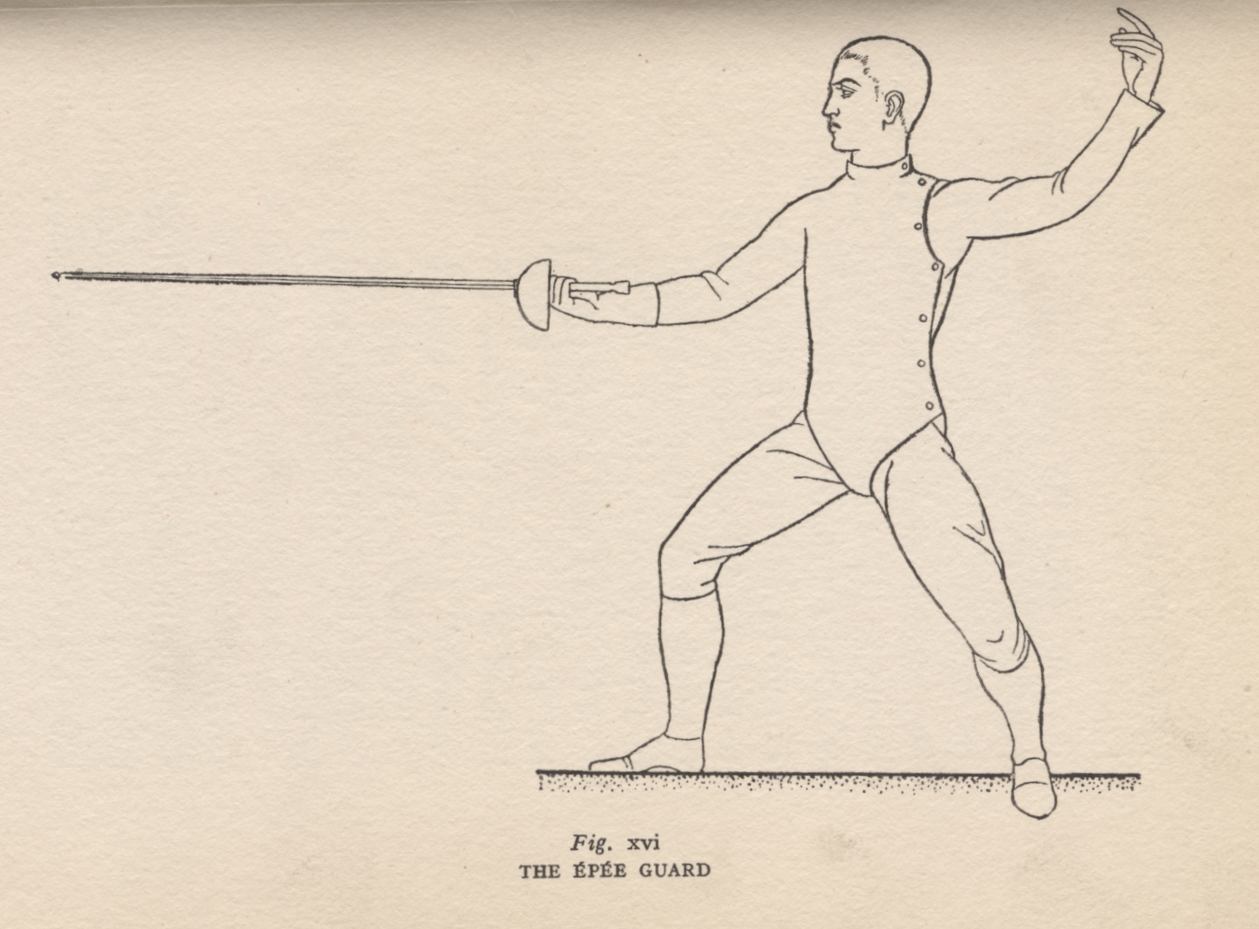

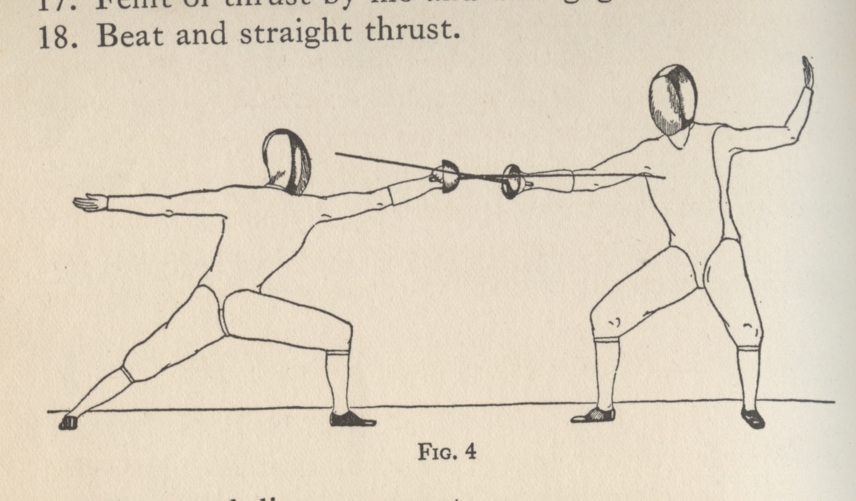

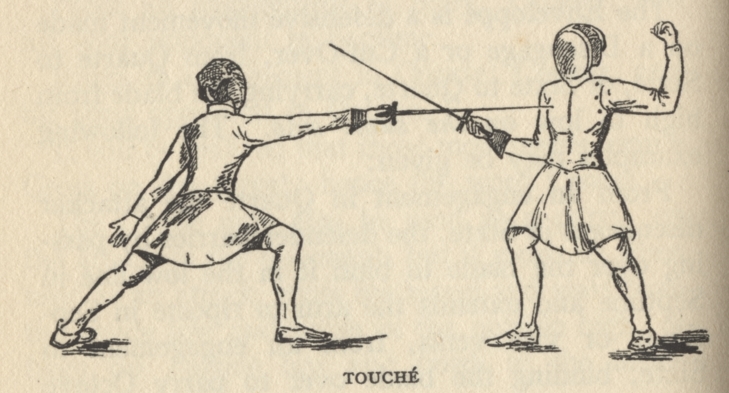

From Crosnier, no explanation necessary.

Fencing with the Epee by Roger Crosnier, 1958. A thorough description of modern classical epee technique, still very useful today. Prof. Crosnier’s book on foil fencing (see the Foil section) should be read hand-in-hand with his epee text.

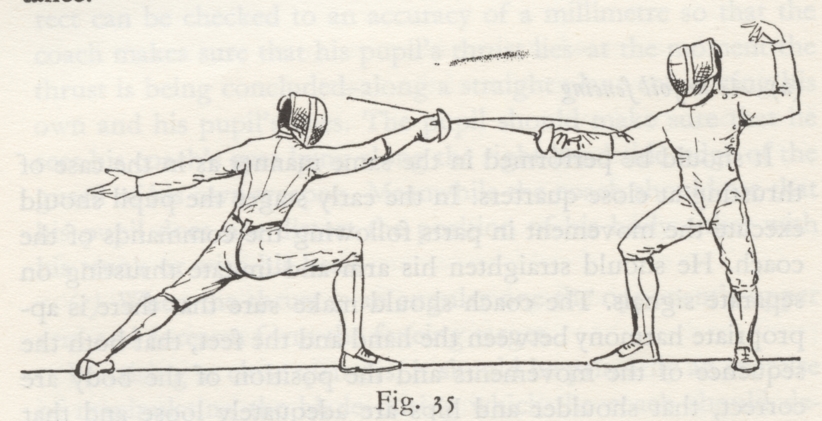

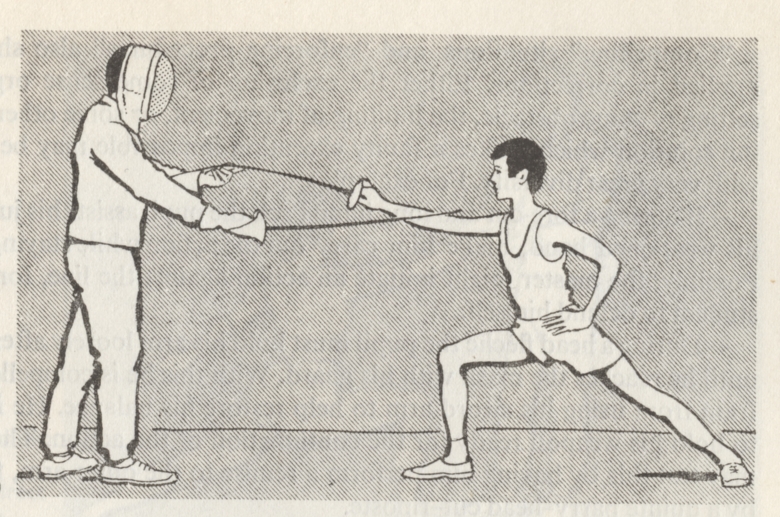

An attack to the arm in the manner of foil, in quarte with opposition. (Does anyone teach foil thrusts in opposition anymore, other than perhaps in sixte? They should.) From Vass.

Epee Fencing: A Complete System by Imre Vass, 1965 in Hungarian, 1976 1st English edition, revised English editions 1998, 2011. The most thorough epee text ever written. That said, highly recommended for epee coaches at all levels, recommended only with caution for intermediate to advanced fencers (at least three to five years or more significant experience)—but not for beginners. There is much useful, often profound, material, but some sections can be skipped entirely by some fencers, and others require sufficient epee fencing experience in order to profit from them. The revised editions were edited by fencer and publisher Stephan Khinoy, and amplify and supplement the original text in places.

The latest edition suggests the need for such classical training today, in spite of the so-called “new paradigm” (see Harmenberg below, his book is also published by Khinoy). I agree; in fact, my fencing master’s thesis (soon finished I hope, albeit delayed by fiction and non-fiction projects, and overwhelmingly by a pre-kindergartner and his younger sister) is based on the same premise. Even for those relatively few fencers (as compared to the entire body of epeeists) who wish to and are able to emulate Harmenberg’s sport methods, a solid base of “modern classical” epee training is still necessary. For most epeeists, even superior amateurs, modern classical technique is all they’ll ever need.

Again, caution is advised when studying the book; it’s best to have a solid understanding of fundamental epee technique and theory before reading it. In fact, it helps to understand the Italian school in order to understand Vass’s theoretical framework: Luigi Barbasetti’s book on foil (see below) is a good start. Vass trained international medalists József Sákovics and Béla Rerrich, both of whom went on to become leading epee masters and national coaches, the former in Hungary, the latter in Sweden, with numerous international champions to their credit. He also trained four-time Olympic gold medalist in epee Győző Kulcsár, who later as a fencing master trained two-time Olympic gold medalist in epee Timea Nagy. József Sákovics, considered by many to be the first “modern” epee fencer, died in 2009, Béla Rerrich in 2005, and Győző Kulcsár in 2018.

La Spada: Metodo del Maestro Caposcuola Giuseppe Mangiarotti by Edoardo Mangiarotti, the Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano, Scuola Centrale Dello Sport, and Federazione Italiana Scherma, 1971. Epee as taught by the famous Guiseppe Mangiarotti: a thorough exposition of his method. Beginner-friendly, too, at least if you read Italian or have a working knowledge of fencing technique and language along with a background in Romance languages other than Italian. Includes excellent illustrations of blade positions, better perhaps than in any other epee text. (Side note: the book even includes illustrations from the works of Vass and Szabo. Kingston and Cheris in this section also have excellent illustrations of blade positions.)

Prof. Mangiarotti, who studied under Italo Santelli as well as under other masters Italian and French, was an Olympic fencer, seventeen-time Italian national epee champion, father of famous champion Edoardo Mangiarotti as well as of noted fencers Dario and Mario Mangiarotti, and founder of a famous epee school in Milan, still in existence, that blended the French and Italian schools and produced champions for decades. Edoardo won 13 Olympic medals and 26 World Championship medals, and was known for his fluid, very Italian footwork as well as for his strategy of attacking hard and fast early on to get touches, then playing a defensive game. Highly recommended: it is my second-favorite “modern” epee fencing book. See also Mangiarotti and Cerchiari in the “Combined Modern Epee, Foil, and Saber Texts” below. For the French school, see Alaux and Cléry in the same section.

Epee Combat Manual by Terence Kingston, 2001, 2004. Highly recommended beginning to intermediate text. Should be required reading for new epeeists. Pair with How to Fence Epee by Schrepfer (below). Unfortunately, Kingston’s book is unavailable in the US anymore, and his web store ships only to the UK and EU (or I suppose he still ships to the EU after Brexit–a lot of small businesses are having issues doing so).

Fencing: Steps to Success by Elaine Cheris, 2002. Actually an epee and foil text, but the epee stands out more to me, and is very useful to both recreational and competitive fencers. Includes training drills as well as excellent illustrations of technique, including from the fencer’s point of view. The book is a good companion to Kingston’s book above. Cheris is one of the great US fencers in both epee and foil.

Epee 2.0: The Birth of the New Paradigm by Johan Harmenberg, 2007. For advanced epeeists and coaches only. There is a second edition–Epee 2.5 I think–that I have not yet read, therefore some or all of the criticisms below might be valid for the new edition. Importantly, the book is suited, in Harmenberg’s own words, only to truly advanced fencers, although this has not stopped many insufficiently experienced epeeists, and even their coaches, from foolishly assuming they can emulate its technique and tactics—and in doing so, impale themselves by repeatedly running onto their adversary’s point from distance much too close. This is often quite funny to watch, especially in the case of exceptionally tall epeeists, with their naturally slower tempo, who throw away their height advantage.

Although there is very useful material in the book, some of Harmenberg’s recommendations are controversial and not all masters agree with the described training regimen, except, again, perhaps in the case of elite epeeists. Further, Harmenberg at times appears to take more credit than he deserves, albeit innocently, given that other epeeists were also knocking at the door of his new style, and had been for some time. Harmenberg, however, was arguably the first elite epeeist to succeed with it at the Olympic and World Championship levels. That is, the first to use “outstripping” attacks—beating the double touch timing by a hair—to the body as a primary technique and tactic, although others, the Soviets notably, had already been using the fleche in renewed attacks to great effect in an outstripping rather than conventional tempo. (Vass calls these sorts of touches “combat” techniques; a better term might be “sport” techniques.) It was also common to see some epeeists below the international level in the 60s and early 70s use technique similar to Harmenberg’s, but they were unable to succeed with it against elite modern classical, aka conventional, epeeists at the international level.

Additionally, some of his criticisms, even though thoroughly honest, of the modern classical technique are not entirely valid. For example, his objection to epeeists who use, and their masters who teach, attacks with a fully extended arm prior to the lunge is somewhat misplaced: although some fencers and masters did adhere to the technique (and some, unbelievably, still do), the lunge with near-simultaneous extension (likewise, “progressive attacks”) was commonplace three or more centuries prior, and also in use again by many masters and fencers beginning a few decades prior to Harmenberg’s era, and some lineages of masters had never taught otherwise. (“Historical” fencers, please don’t bother to argue with me on this smallsword history, simply open up and read the first two dozen period smallsword manuals you lay your hands on.)

Even so, many early epee masters did teach that the attack via lunge, almost always to the arm, must be made with the arm fully extended first, although others argued correctly that simultaneous or near-simultaneous extension and lunge was faster, as Harmenberg likewise deduced (as did masters in past centuries). Indeed, if you intend to hit the body with an attack, you’d better not extend first then lunge! If you do, you’ll lose a tempo, warn your adversary, and probably get successfully parried or counter-attacked. Early epee masters generally avoided recommending attacks to the body due to the increased risk of double touches—and the increased risk of jail time for murder or manslaughter. (Roughly seventy percent of modern epee touches are made to the body thanks to the flat tip of the epee which is less effective to the arm when compared to the old jacket-tearing points d’arret which were highly analogous to the sharp point of a dueling epee.)

The argument remains as to whether Harmenberg’s described techniques and tactics are truly revolutionary, or merely one of the final steps in the evolution of sport epee, in that the “paradigm” takes complete advantage of the 20th to 25th of a second tempo provided by the electrical apparatus, and entirely disregards any consideration of classical tempo so necessary were swords real — sharp, that is, and intended to put holes in an adversary.

Put plainly, the book is Harmenberg’s exposition of how HE fences. Tellingly, whenever I ask elite European fencers and masters about the book, they shrug their shoulders. If they do happen to know who Harmenberg is, their answer is something on the order of, “Well, if it worked for him, good, but there are many other ways to fence epee…” That said, far too many epee teachers in the US have adopted his theory, all too often too early for their students and quite imperfectly, although lately I see this fad–and there are many fads in fencing–fading.

The book is based on the Swedish epeeist’s experiences leading up to his 1977 world championship and 1980 Olympic gold. In other words, however profound the book may be to sport fencing, its author’s ideas were not new in 2007—only their publication was.

Epee Fencing by Steve Paul et al, published by Leon Paul, 2011. A very useful text for the modern competitor. Positive criticisms: thorough and well-illustrated. Negative criticisms: 100% emphasis on epee as pure sport (as opposed to epee as dueling swordplay or martial art modified for sport) and a magazine-style layout (or in imitation of a badly-designed webpage?), including a thin magazine-like cover that will not hold up to much wear.

How to Fence Epee: The Fantastic 4 Method by Clément Schrepfer, 2015. Translated from the original French edition, Faire de l’épée: La méthode des 4 fantastiques, by Brendan Robertson. Not a manual of technique per se, but suggestions on how to use it. A very useful book, with only little to find disagreement with, and mostly in terms of style or tradition and not practicality. Highly recommended, especially for beginning to intermediate epeeists. An excellent companion volume to the Epee Combat Manual by Kingston (above) or Learn Fencing — Épée below.

Learn Fencing — Épée by Peter Russel, 2015. A generally good introduction to modern epee for beginners. Quibbles: the black background and resolution of some of the photos makes for difficult viewing and therefore comprehension at times, and the description of beats is inadequate, essentially relegating the beat to a reconnaissance action with the foible. This may be an artifact of the ignorance of the beat many modern fencers have (I blame their coaches for following the fad of not teaching a complete technique). Numerous times over the past fifteen years I’ve been told by visiting fencers that they’ve never encountered a beat as strong as mine and suggest I must have extraordinary forearm strength. Nonsense! It’s all technique! My wife, smaller and less strong than I am, has a beat as powerful. As Vass (noted above) put it, the beat (use the middle of the blade, not the foible except for reconnaissance) can be used to open the target, delay the adversary’s response, provoke a reaction, and loosen the adversary’s grip, thus further delaying the response. Enough ranting. 🙂 (Last quibble: poor copyediting on the cover, in which Épée is spelled Épeé, but books shouldn’t be judged by their covers.)

See also the “Combined Modern Epee, Foil, and Saber Texts” section, especially Alaux, Barth/Beck, Cléry, de Beaumont, Deladrier, Lidstone, Lukovich, Mangiarotti/Cerchiari, and Vince, as well as the “Epee de Combat” section in general, and Castello and Gravé in the “Classical Fencing” section.

The Epee de Combat or Dueling Sword:

Epee for Actual Combat, In Other Words (and Almost Immediately for Sport as Well)

All of these works are of use to the modern epeeist, and all demonstrate that there is, overall, little new in modern epee fencing. Even the pistol grip was growing in popularity in France by 1908, although its use in dueling was prohibited and it would be the Italians who found in it the perfect replacement for their rapier grip. Only the tactics and techniques of “out-stripping” (of trying to hit a 25th to a 20th of a second before one gets hit), and of the unrealistic abomination of flicking (and arguably, of foot touches), are new. In fact, by 1900, if not earlier, epee was often judged not according to the realities of sharp swords, but according to a perceptible difference in timing when both fencers hit–in other words, who hit first, much akin to the modern electrical apparatus (unfortunately).

Double touches, including “outstripping” touches of which modern epeeists are so fond (hitting just enough prior to the adversary’s hit that it will be considered a single touch, when with real swords both fencers would be hit) have long been the bane of the salle or sport fencer, even long before the advent of electrical scoring and its too short timing–there have always been fencers trying only to get the first hit, however they may, as if playing tag. There is an unfortunate natural tendency to turn fencing into a game of mere “who hits first” tag. As for the flick, it is new only to epee: it was used by a fair number of foilists in the 19th century and almost certainly in the two immediately prior centuries as well. Flicks and foot touches are too dangerous to attempt with an epee de combat: they would cause little damage while leaving the user vulnerable to more damaging, even fatal, thrusts, not to mention that the blade of a real dueling epee is too stiff to permit the flick. Some old dueling epee masters even proscribed the “thrown thrust” common in epee, because, like the flick would if it could be used with a dueling sword (it can’t because the dueling blade is too stiff), it wounded only the skin, not the muscle beneath; the latter wound was more likely to end the contest.

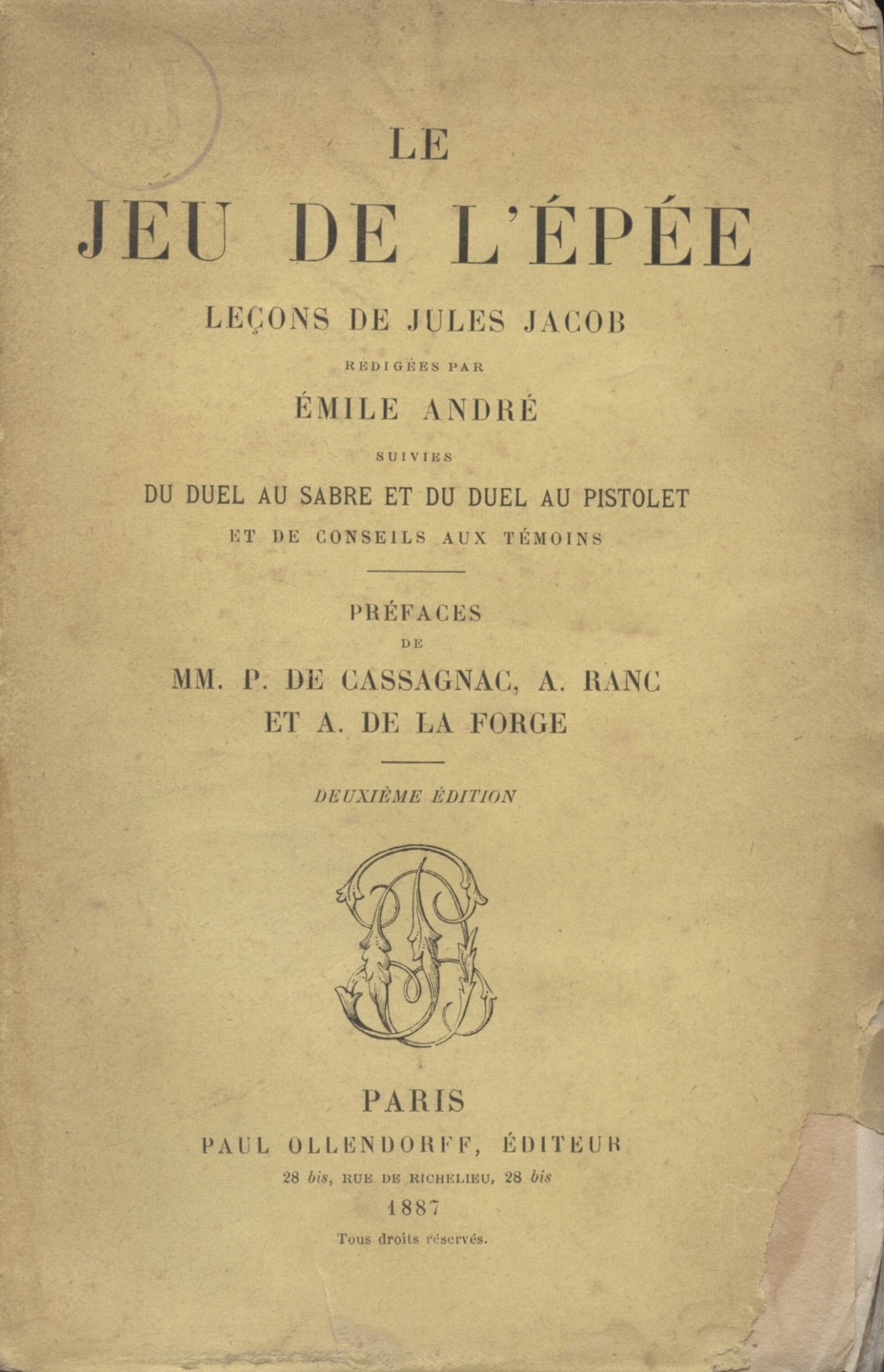

Le jeu de l’épée by Jules Jacob, as reported by Émile André, 1887. Lessons of the fencing master who essentially created modern epee in the 1870s. By the third quarter of the19th century the foil had become a “weapon” of pure sport, although it had been heading in this direction since the late 17th century. M. Jacob adapted smallsword technique to create a form of swordplay suitable to surviving a duel with the 19th century épée de combat, or mere epee, as its modern descendant is called. The technique emphasized longer distance and hits to the arm—and thereby also reduced convictions for manslaughter and murder. It some came to be known as the “modern school,” as opposed to the “traditional school”–foil fencing, that is.

The book outraged many foil purists, who subsequently went into sophistic denial when his epee technique proved far superior to foil technique in a duel: Jacob’s less technically proficient epeeists were deadly against even highly skilled foilists, who maintained that the only difference between the technique of the salle and of the duel was the accompanying mental attitude. (If true, attitude was clearly deficient among the fleurettistes who fought duels with Jacob’s épéistes.) The book plainly points out the difference between the jeu de salle (sport fencing) and the jeu de terrain (swordplay of the duel), and reminds us that many of the best duelists were usually not “forts tireurs”—good sport fencers, that is. The same would doubtless be true today. Highly recommended. There is, I believe, an English translation now available.

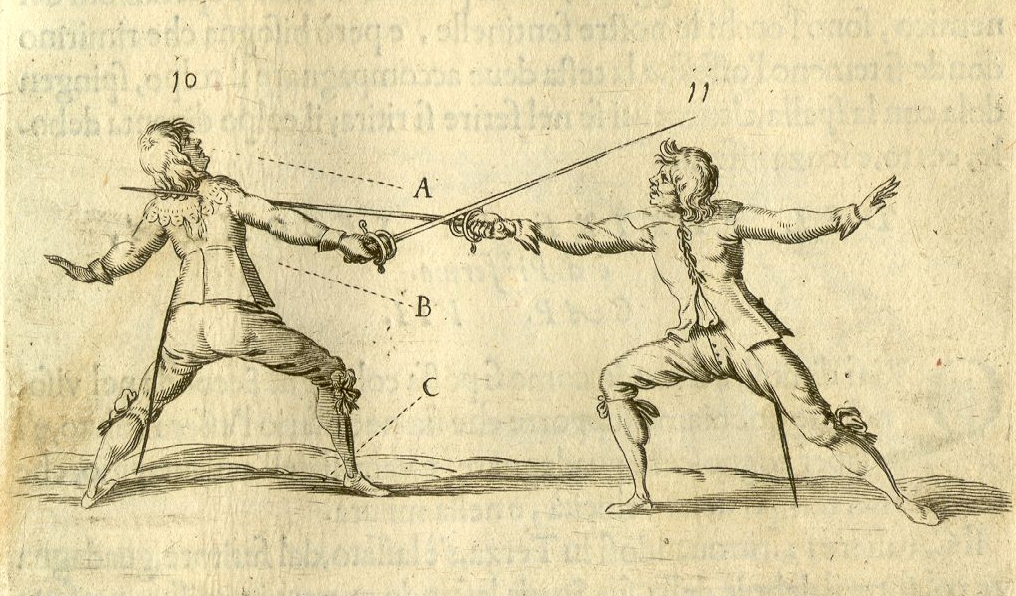

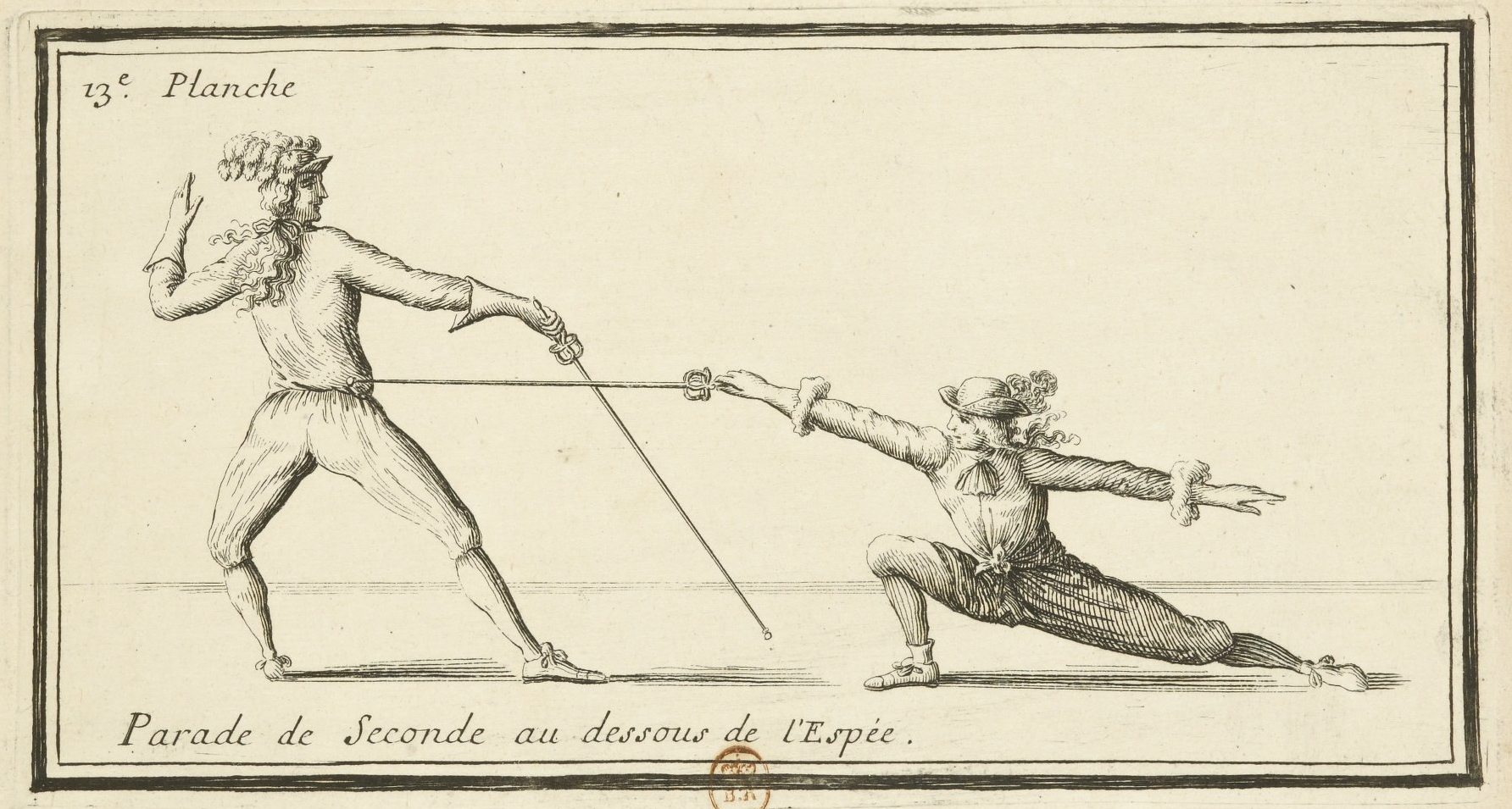

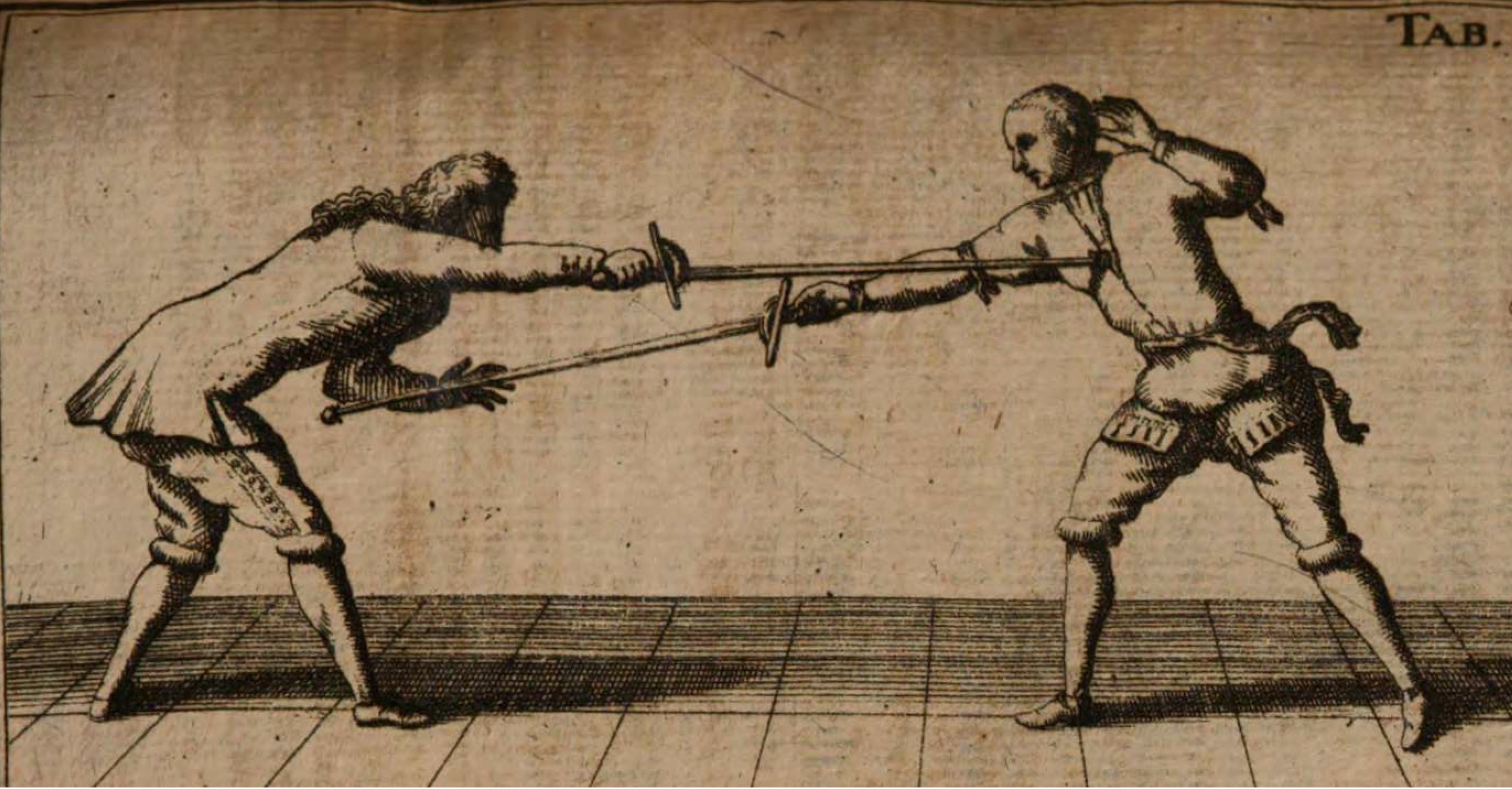

From La Marche. Note the en garde with unarmed hand pressed against the hip, unusual even when the book was published, but La Marche had his reasons.

L’Épée by Claude La Marche [Georges-Marie Felizet], illustrated by Marius Roy, 1884, reprinted 1898 or 1899; also The Dueling Sword, an English translation edited and translated by Brian House, 2010. Very thorough, and in its translation was for a long time the only early French epee and epee dueling manual available in English. Real swordplay, in other words, and useful even to epeeists today. To a degree the book is a somewhat foil-based response to the purely epee-based technique of M. Jacob (see above). M. La Marche differs from M. Jacob on some points, particularly on the value of attacks to the body, of which M. La Marche is in favor, as were smallswords-men (and smallswords-women).

The modern trend in epee, at least at the elite levels, and among instructors who train less skilled fencers as if they were elite fencers, emphasizes attacks to the body. Where to emphasize attacks—arm or body—has been an ongoing re-argument ever since the flat electric tip was introduced to replace the much superior “pineapple” tip in the early 1960s, rendering arm shots more difficult. The epee fencing argument over arm versus body derives from late nineteenth century dueling practice—arms hits could easily settle honor in the modern age in which killing a man in a duel would surely send the perpetrator to prison, and the longer distance that facilitated them was simply safer. For reasons that would take up too much space here in discussion, the body was also the primary target in the smallsword era—but the dangers of this distance were mitigated by the use of the unarmed hand to parry and oppose as necessary, and by the extensive use of opposition and prises de fer. Similar varying perspectives are seen in sport epee today. Notably, and often forgotten by some fencing teachers, roughly thirty percent of epee touches today are to the arm, not the body, even with the emphasis on the body as the better target for the flat modern epee point. A highly recommended book, and useful even to modern competitive epee fencers.

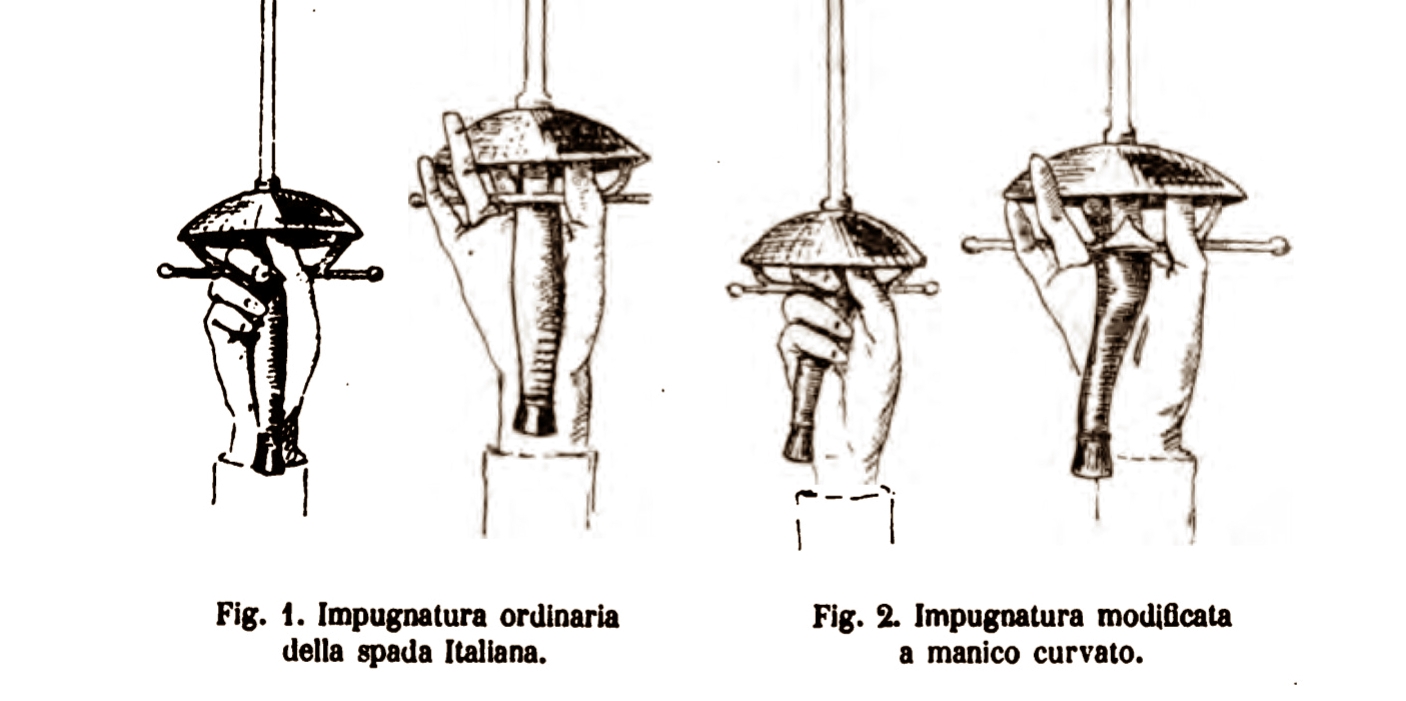

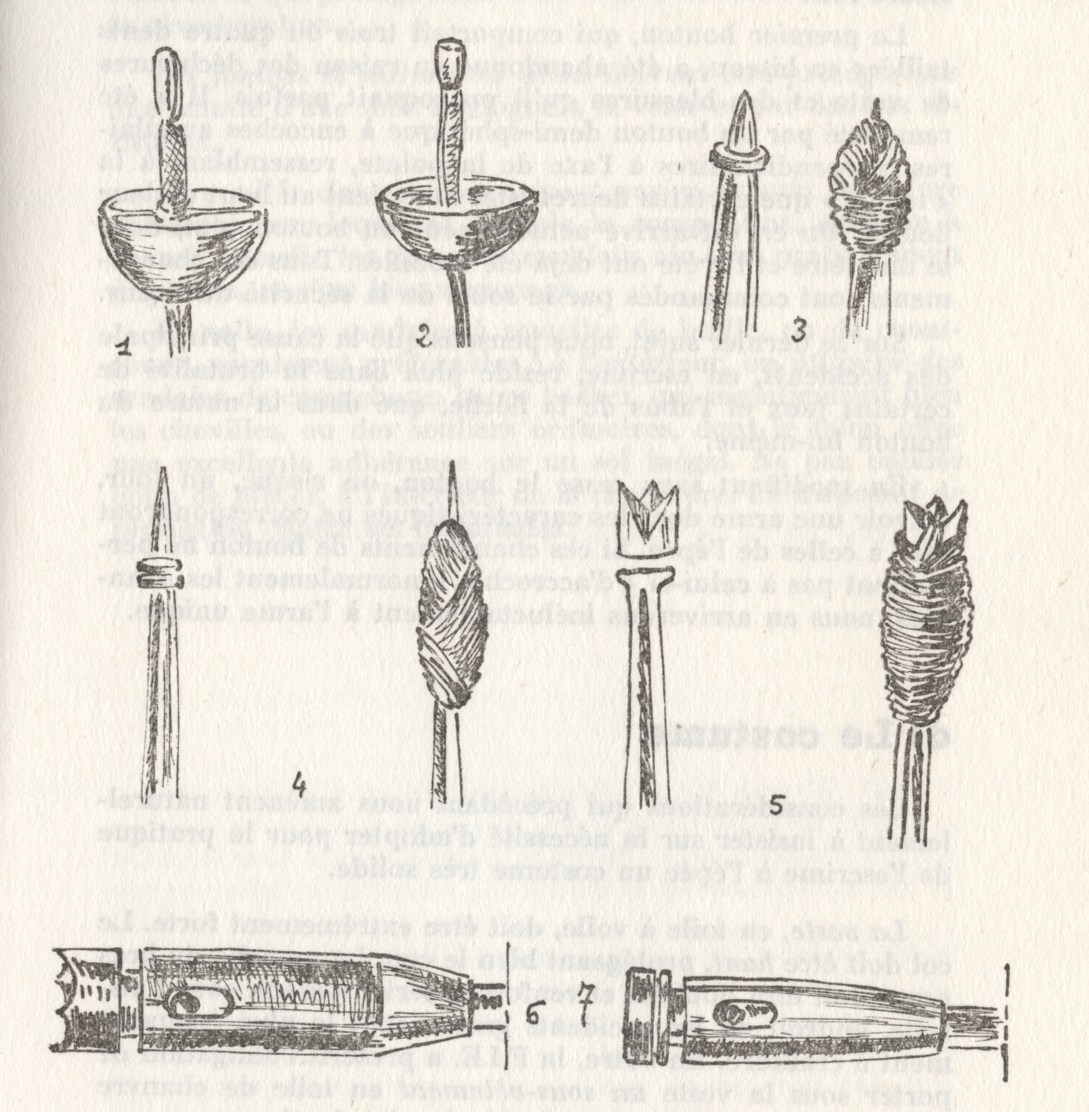

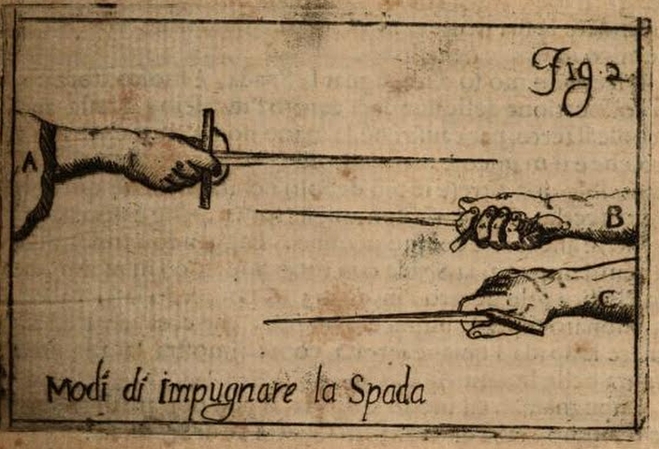

Italian grips and how to hold them, Rossi 1885.

Manuale Teorico-Pratico per la Scherma di Spada e Sciabola by Giordano Rossi, 1885. A manual of the Italian dueling sword and dueling saber, very practical, very classically Italian although it does include some “modern” usages, including a choice of Italian spada with a curved grip, akin to a later French grip, with a significant set to the blade, although it doesn’t seem that this style of Italian grip won many fencers over–but did it perhaps influence the French to increase the curve of their grip? I haven’t seen any French foils or epees circa the 1880s with such a severe curve. The book demonstrates a technique quite useful to epee, and in fact the influence of the Italian school would become a significant part of modern epee.

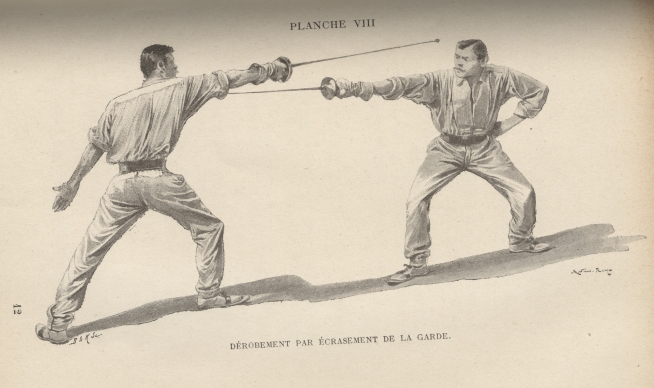

L’Art du Duel by Adolphe Eugene Tavernier, 1885. Advice on dueling. Suggests tactics and techniques for the epee duel, including how to deal with the inexperienced adversary, the average one and, of course, the expert swordsman. Of interest to the student of fencing history and the duelist, and one of the few books to deal with the subject of tactics against fencers of various levels of competence.

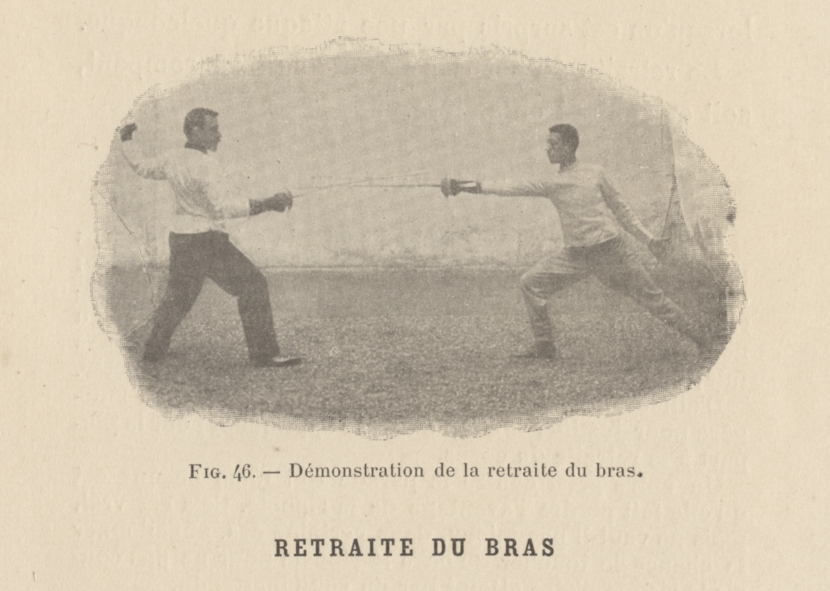

Withdrawing the arm, still used–overused by some, to the point of being considered an en garde position by some masters and their students–today. Useful for preventing hits to the arm and forcing the adversary to attack the body instead, assuming of course the adversary is so impatient as to give in to the tactic. It could also be a dangerous tactic, given the dangers of a successful thrust to the torso. From Spinnewyn.

L’Escrime a l’épée by Anthime Spinnewyn and Paul Manoury, 1898. Excellent work on the epee de combat, with much practical advice on epee fencing, training, and teaching applicable even today. Among the many worthwhile admonitions is that the recovery from the lunge is just as important as the lunge itself–both must be as fast as possible, especially if the epees are pointed.

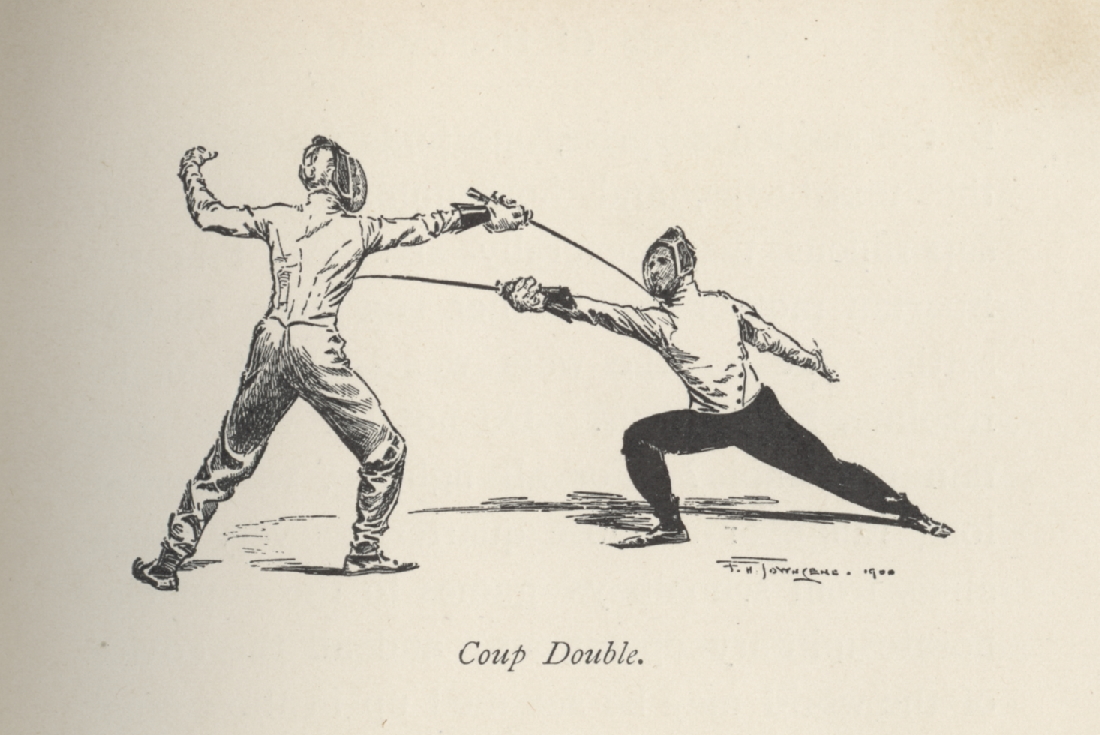

The “coup double” (double touch) as depicted by F. H. Townsend in Secrets of the Sword by the Baron de Bazancourt, 1900 (English translation by C. F. Clay of the original 1862 French edition).

Les secrets de l’épée by Baron César de Bazancourt, 1862, published in English as Secrets of the Sword in 1900, reprint 1998. Practical advice on hitting and not getting hit from the mid-19th century. Much of the advice sounds quite modern. Likewise highly recommended.

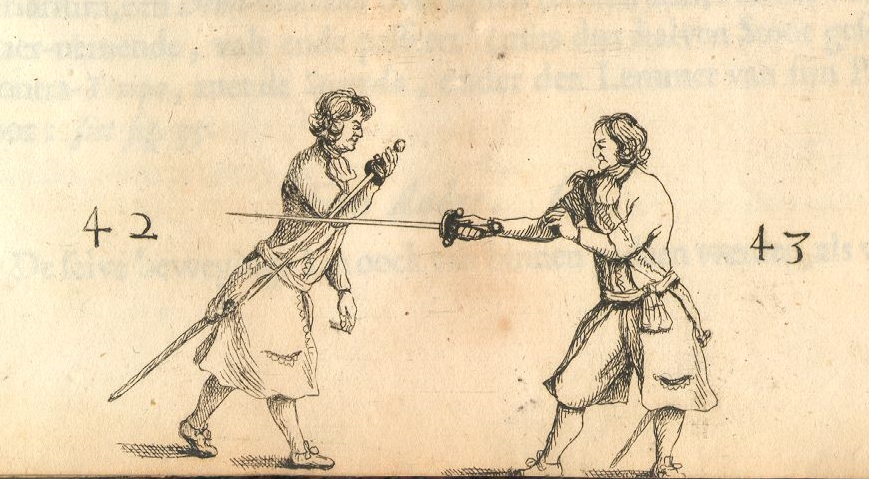

Seconde parry against a direct thrust. The seconde parry, as with all low line parries in epee, may be effectively used in the high lines as well. From Edom.

L’escrime, le duel & l’épée by Achille Edom, 1908. A remarkably prescient and practical work, one of my favorites, and one that demonstrates plainly that there is little new in epee fencing today. In particular, M. Edom, a Frenchman, recommends the more physical Italian style over the French, prefers the Greco offset guard and the pistol grip, and bemoans the rise of sport technique such as wide angulations to the wrist—thrusts that with dueling epees (with sharp points, that is) would not stop a fully developed attack to the body, leaving the attacker with a wound to the wrist, and the attacked with a possibly fatal wound to the chest, neck, or head.

The origin of these angulations was due much in part to the single point type of point d’arrét used by many at the time: a small ring was soldered to a real pointed blade a centimeter or so from the tip, then wrapped with heavy thread to act as a barrier to full penetration. Unfortunately, this heavy wrapping prevented hits at the shallow angles a real point was capable of, thus a new emphasis on unrealistic wide angulations. The three point “dry” and four point electrical, and later “pineapple” electrical points d’arrét greatly corrected this, but the subsequent modern flat point (brought into use in the early 1960s in order to quit tearing up the new nylon jackets perhaps?) inspired the popularity of severe angulations once more. In fact, almost any stop thrust to the arm would not arrest a fully developed attack, although you might have the satisfaction, as your adversary’s attacking blade penetrates your chest, of pinning his (or her) arm to his (or her) chest as he (or she) runs up your blade. Highly recommended.

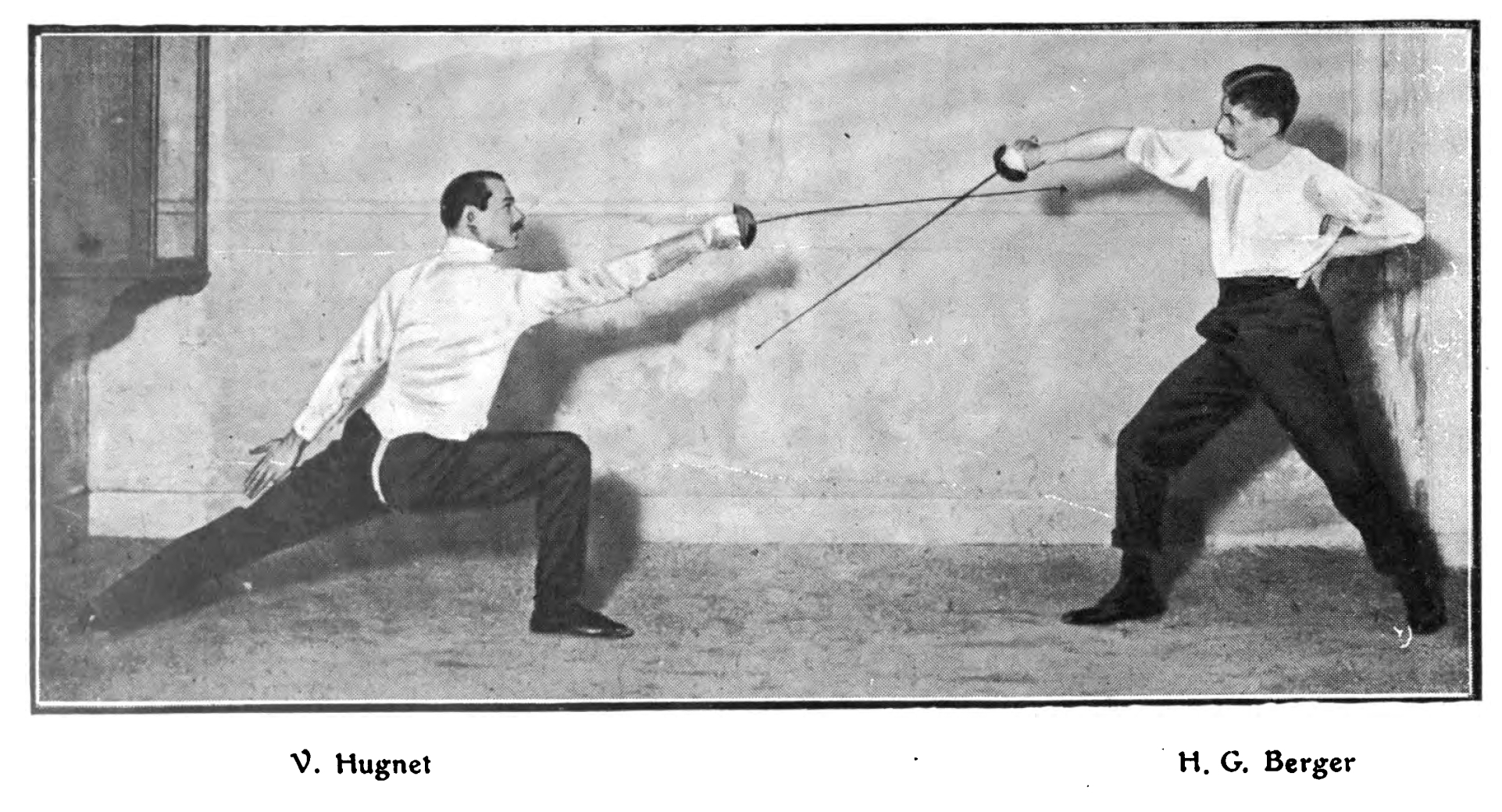

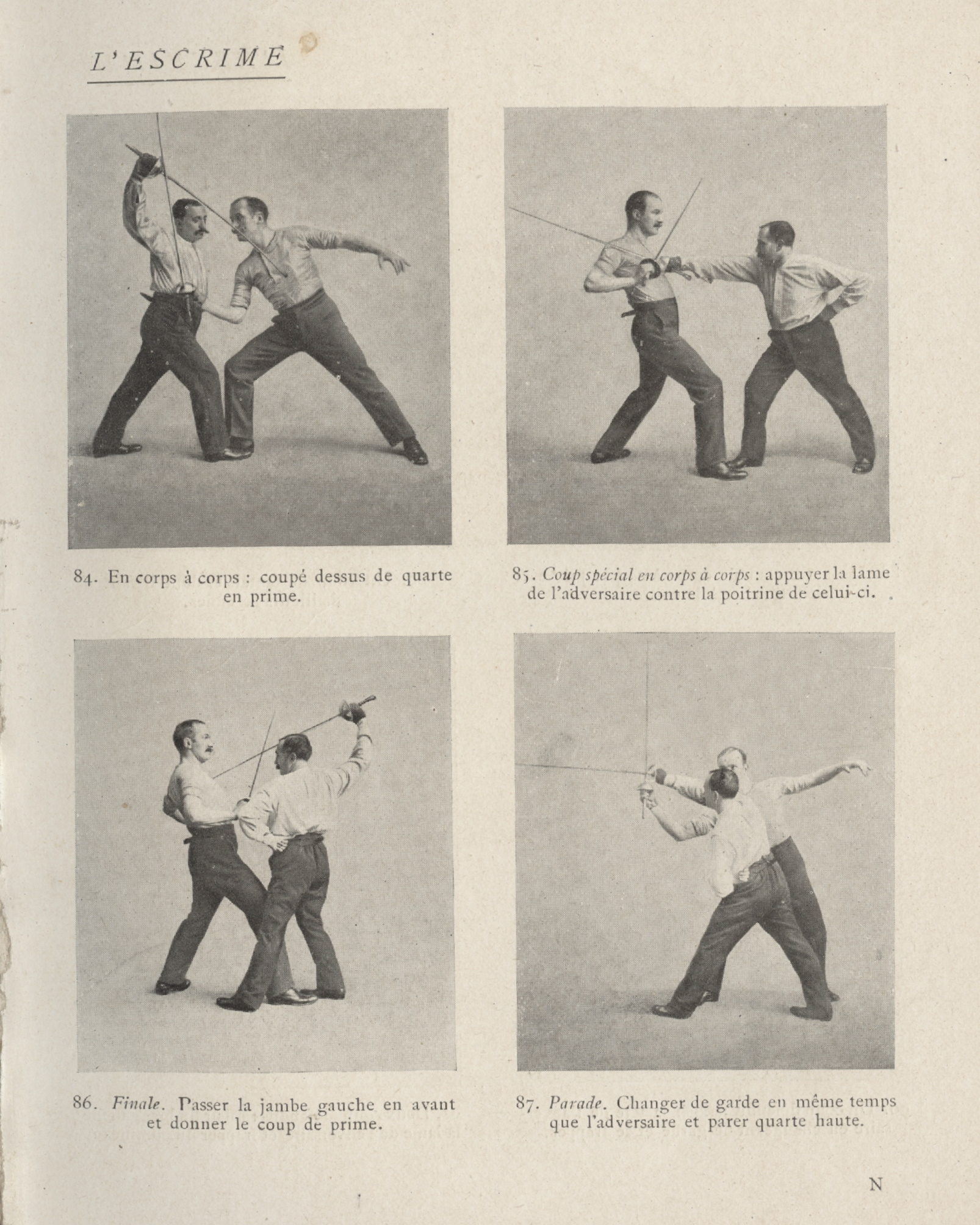

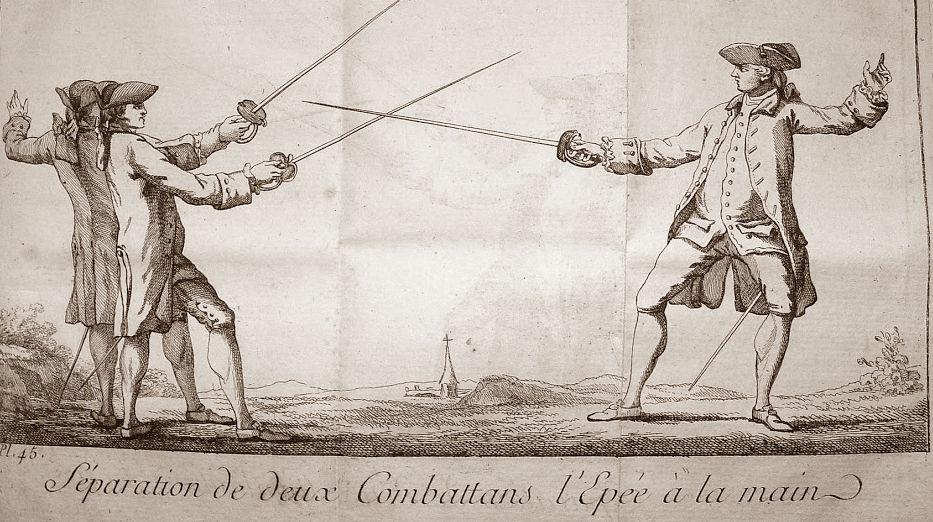

Close combat, as depicted by J. Joseph Renaud. In practice, the directeur de combat would halt the duel prior to such potentially deadly antics. Even so, the circumstance could arise and the duelist must be prepared. Side note: for decades the term for fencing referee in the US was directeur de combat, taken from dueling. It was changed within my fencing lifetime to referee in order to, literally and nonsensically, “make fencing easier for the audience to understand.”

L’Escrime by J. Joseph-Renaud, 1911. One of the best of a number of outstanding epee books published during the Golden Age of epee and of books on the subject, by far. The author does by far a superior job explaining the faults in French foil for dueling, comparing French foil to Italian (thus explaining why Italians successfully trained with their foil for the duel with the spada or epee de combat but the same could not be said of the French), and explaining a wide variety of epee technique, both that which is correct and that which is faulty but commonly seen. Thoroughly illustrated with photographs, the volume is of great use to the modern epeeist, historical or classical epeeist, and fencing historian and theorist. Joseph-Renaud is a member of the community of epee masters for whom the lunge must always be preceded by a fully extended arm, and he does not recommend attacks to the body. Much of the reasoning for this is to protect the duelist from a potentially mortal wound in himself or in his adversary, the latter of which would result in criminal prosecution and the former of which, well… In fact, as smallswords-men of past centuries, and even the author himself, knew, the lunge with the arm extending near simultaneously (just a hair ahead, that is) is the fastest attack by lunge, and mandatory if one is attacking the body, not the arm.

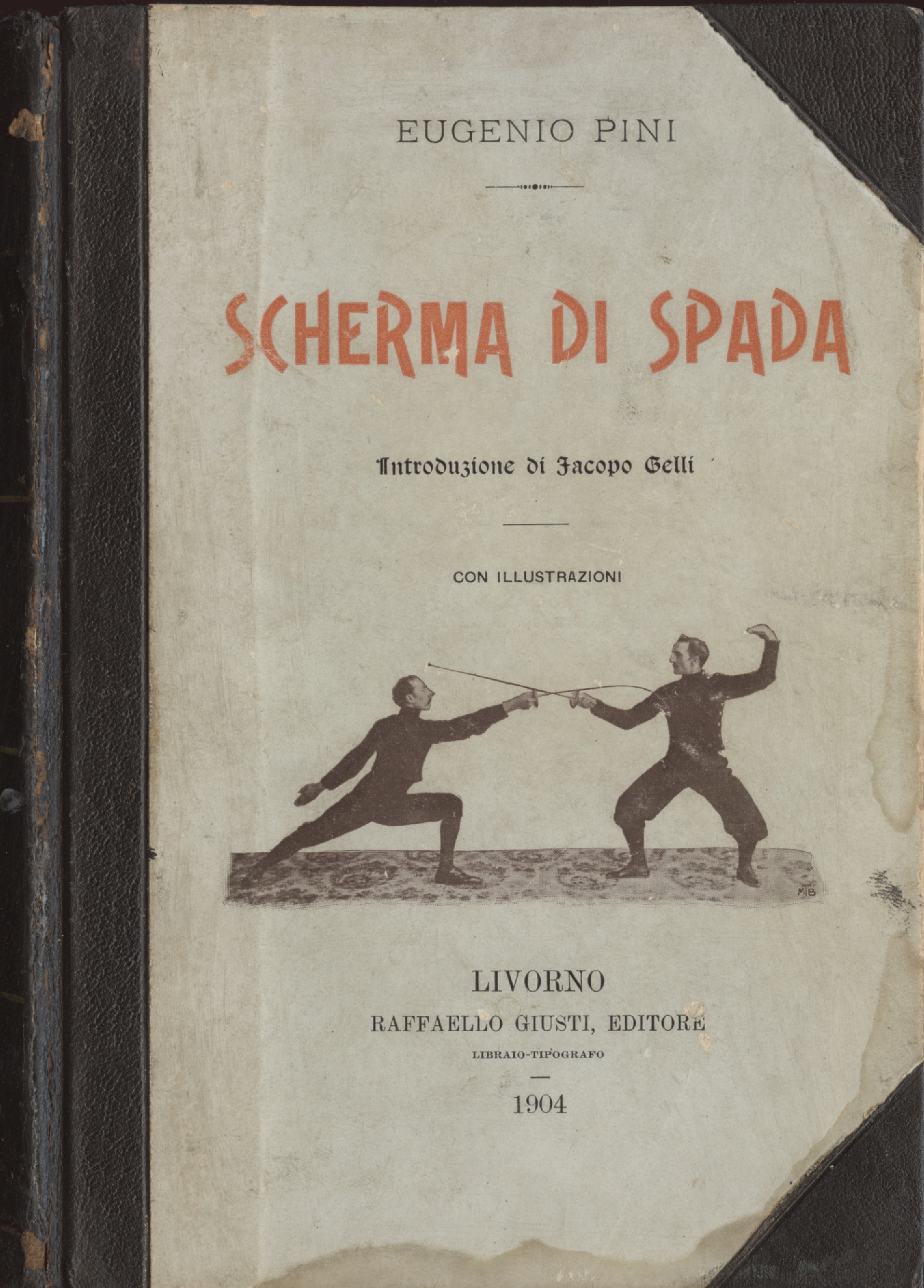

Tratto Pratico e Teorico Sulla Scherma di Spada, by Eugenio Pini, 1904. Excellent and thorough practical treatise on swordplay with the Italian spada or dueling sword by the Italian master who epitomized a form of swordplay that emphasized physical strength and speed–no, this emphasis isn’t new to fencing, nothing really is, in fact. At the time the book was written, the school of the Italian dueling sword was based on the fioretta or foil, which was used for training instead of the spada itself. Pini points out correctly that at the time the French schools had separated foil from epee, and epeeists were now taught with the epee rather than the foil, although this would soon change as French foilists, unhappy at being usurped by the “modern school” of epee and its epeeists, would attempt to reassert their dominance via a foil-based school of epee. For a long time the Hungarian school, via the Italian, kept up this tradition of training epeeists first as good foilists. In fact, it’s how I was trained more than forty years ago. However, the modern divergence between foil and epee has made this almost impossible.

The Sentiment of the Sword: A Country-house Dialogue by explorer, adventurer, linguist, scholar, writer, and swordsman Sir Richard Burton, 1911. As with Bazancourt’s book which inspired this Anglo version, not strictly an epee manual, but still useful for understanding swordplay in the sense of the need to hit and not get hit, as opposed to hitting according to conventions which deny touches not made in accordance with said conventions, but which in a duel would be quite real, and in many cases fatal. (Thus the practical and, if in a duel, fatal flaw in foil fencing.) Burton’s book also has some quite modern advice on learning to fence. Burton had used a real sword many times in bloody combat, and was known as an extraordinarily fierce warrior. Highly recommended.

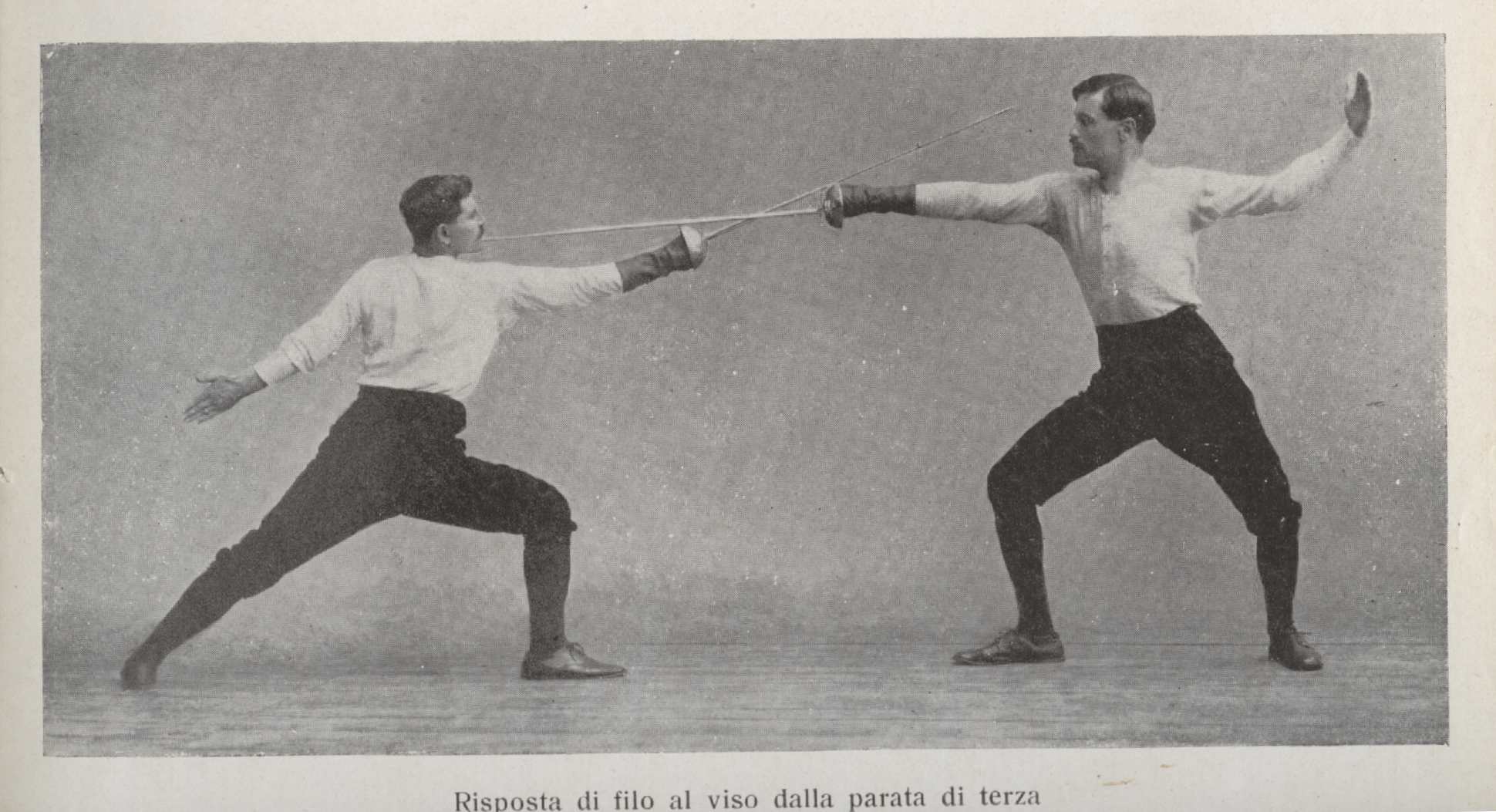

Filo (bind thrust) riposte to the face after a tierce parry. The face as a riposte target (it’s much easier to hit than the shoulder), or even as a counter-attack target (it’s unexpected), is sadly undervalued by many modern epeeists. From Greco’s book.

La Spada e la Sua Disciplina d’Arte by Agesilao Greco, 1912. Another of my favorites: a practical, very Italian text on the dueling sword, with, among other things, demonstrations of the Italian grip versus the French (e.g. showing that opposition with the Italian grip can overcome the extra length afforded by holding the French grip toward the pommel) and, a rarity in epee books, French especially, numerous bind thrusts to the head (filo al viso; in fairness to the French, Joseph Renaud describes and illustrates a stop thrust au visage with esquive). Greco advocates four parries: prime (a sixte taken with an extended arm), tierce, quarte, and seconde.

The text also includes many examples of filo thrusts (bind thrusts, strong opposition thrusts) to the torso, which are often downplayed in French texts of the era, given the possibility of killing one’s adversary with them (better to hit the arm a few times and go home than worry through an investigation and possible conviction for manslaughter or murder; some period French texts do discuss these thrusts, particularly those of the “foil-epee” and “foil” French dueling schools). The book also includes descriptions of the Italian spada (noting that at the time they were of equal length, i.e. the Italian had a slightly longer blade), clothing and equipment, &c. The photographs are clear and well-posed. Unbelievably, my copy, signed, was never read: most of the pages are still uncut. Highly recommended.

Agesilao Greco was, along with his brother Aurelio, the greatest of a great family of fencers dating to the mid-19th century. The brothers highly influenced the Italian form of epee fencing for both dueling and sport. The Greco Academy of Arms in Rome still exists and still trains world class fencers. It also has a nationally-recognized fencing museum, the Casa Museo Accademia d’Armi Musumeci Greco that I’ve been told is well worth visiting. Greco’s description of the dueling spada is as elegant as the sword is; I’ve included it here and here.

Épée, par J.-Joseph Renaud, 1913, in L’Escrime: fleuret, par Kirchoffer; épée, par J. Joseph Renaud; sabre, par Léon Lécuyer. Excellent advice on training, competition, and dueling, including a technical argument and diagram describing when to use sixte and its counter, and when to use quarte. This latter matter is more important than it seems, for most fencing instructors teach the usual parries and imply that any of the two classical French parries can be used in their appropriate quadrants in any circumstances (true in theory but not in practice) and should be varied in order to keep the adversary guessing (true in both theory and practice, but often difficult given that most fencers under stress have a preferred parry).

There are instances in which only a single parry—even in epee and smallsword, in which low line parries may be used in the high line as well, often providing several possibilities in each quadrant—is viable. For example, quinte (low quarte) against a powerful wide-angled attack, especially if directed toward the abdomen. Any other parry will often be forced or will fail to defeat the angulation. In fact, this is why the quinte parry was introduced. Or, against a wide, high, powerful, angulated thrust to the body in the high outside line (same handed epeeists), in particular when delivered via flèche by a tall strong fencer with his hand in tierce, a circle-sixte or even a circle-tierce will likely be forced even if timed well. A true prime will not defeat the angulation, and a common septime (Italian prime, mezocierco) must be taken too far out of line, exposing the arm to a simple disengage over the top. Octave and seconde cannot be taken effectively, for they too are likely to be forced. Only quarte or quinte (really just a low quarte) taken with the point out of line, with a riposte to the head or possibly the neck or shoulder, is viable in most cases. A modified prime (high sixte/septime) can work but can be difficult to execute if the attacker is tall and strong. Best to stop such attacks on their preparation.

The book includes a discussion of the Italian school. Although M. Renaud grudgingly admits that Italian foilists are equal to their French counterparts, he disparages Italian epee and by implication its rapier origins, stating categorically that the French invented epee fencing and the Italians were no match for French epeeists. In fact, the Italian epee school would soon rise to equal prominence with the French, with Edoardo Mangiarotti becoming one of the great epeeists of the 20th century. (These include Frenchman Lucien Gaudin of the early 20th century, Hungarians József Sákovics and Győző Kulcsár of the mid- and late century. Johan Harmenberg (1976 – 1980) should probably make the list as well. Were I to include possible twenty-first century epee greats as well, I’d suggest Timea Nagy and Géza Imre of Hungary, and Laura Flessel-Colovic of France. Doubtless other epeeists could join this list.)

Naturally, M. Renaud avoids any discussion of what might happen were French epeeists to trade their epees for Italian dueling spadas. Compare his comments on the Italian school to those of Achille Edom above. Side bar: he notes that most French epee schools of the era had outside gardens for practice, in addition to the indoor salle. Pity we don’t have these today…

“Technique du Duel en Une Leçon Suivi des Règles usuelles du Combat à l’épée” by Georges Dubois, published in La Culture Physique, 1908. Excellent work based on the author’s experience preparing would-be duelists for the duel, including those who have never held a weapon before. Disposes with many myths regarding dueling: he points out that most duelists weren’t fencers, and suggests that the epee was designed to help keep both combatants alive and thereby avoid the charge of manslaughter or murder. Never was a weapon so well designed to keep adversaries from killing each other, the author notes.

See also the “Classical Fencing” section below.

Combined Modern Epee, Foil, and Saber Texts

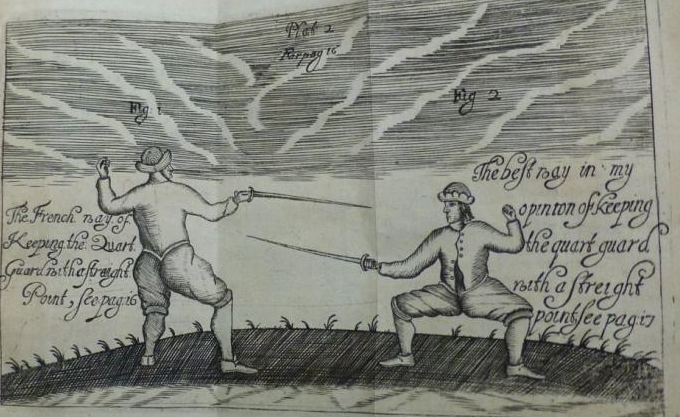

Lidstone, 1930.

The Art of Fencing by R. A. Lidstone, 1930 and Fencing: A Practical Treatise on Foil, Épée, Sabre by R. A. Lidstone, 1952. The second significantly revised book is more thorough, with a very useful, clearly written epee section with plenty of exercises for master and pupil. Discusses tactics, unusual epee en gardes, and, in the foil section, unusual displacements, most of them Italian. It even describes Professor Guissepe Mangiarotti’s “jump back”—an epee counter-attack made while leaping back and landing on the front foot. The second edition is an excellent practical work drawing from both the French and Italian, highly recommended. In fact, along with Szabo’s work, one of the most useful books on fencing on this entire page. For fencing historians, a comparison of the first edition to the second edition shows how much, and how quickly, modern fencing changed during the first half of the twentieth century.

Fencing by Joseph Vince, 1937, 1940, revised edition 1962. Illustrated by US saber champion, designated Olympic team member (until he suddenly abandoned competitive fencing for the stage), and swashbuckling actor Cornel Wilde. Vince was a US national coach and national saber champion who kept a salle in Beverly Hills for decades, and, until 1968 when he sold it to Torao Mori, owned Joseph Vince Company, a fencing equipment supplier that provided, among its complete line, classically dashing fencing jackets of a fit and style unfortunately no longer seen. In fact, my first fencing jacket was a “Joseph Vince, Beverly Hills” made of a heavy, high thread count cotton with silver-colored buttons. The left, that is, unarmed, sleeve was lighter and cuffed. An elegant style truly to be found no more.

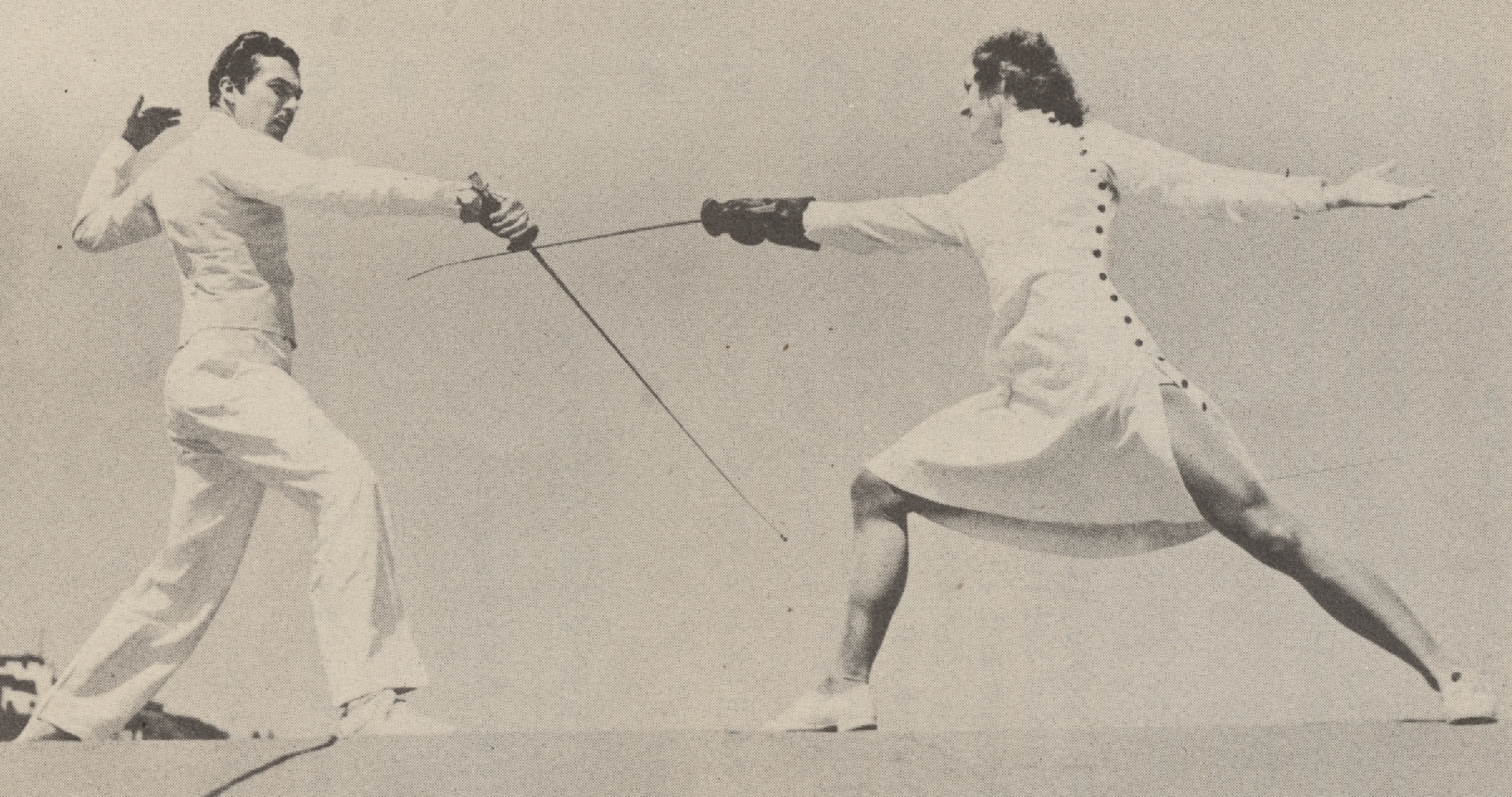

Lunging in women’s fencing dress–quite literally–in Lawson’s book.

Fencing for All by Victor E. Lawson, 1946. The front cover gives the title as How to Fence. A very short basic text, only slightly more than a pamphlet, notable only to the fencing historian, particularly him or her interested in the history of women’s fencing. Lawson’s book actively promotes women fencers, although most appear to be aspiring actresses and models, and the caption of one photograph strongly suggests that Lawson’s goal is to promote his fencing salle in NYC as a means of attaining poise &c for actresses (I use the now generally discarded feminine of “actor” here because “female actor” sounds a bit stilted, and in Lawson’s day he appears to have been recruiting women primarily, not men). Notwithstanding his purpose, Lawson’s little book does actively promote women fencers, and has several useful photographs of women in fencing attire of the 1940s, quite different from today. It also has a good summary of fencing rules at the time. Other titles in the series include Police Jiu Jutsu, Scientific Boxing, and How to Be a Detective–everything to to prepare the reader to be the dark sword of a film noir.

Modern Fencing: A Comprehensive Manual for The Foil—The Epee—The Sabre by Clovis Deladrier, 1948, reprint 2005. Strong epee section. Includes exercises, lesson plans, and excellent practical advice. Readers should not be put off by some terms and practices that seem dated, for example Deladrier’s use of the classic older terms low quarte for septime and low sixte for octave, and his preference for the center-mount epee guard. The epee section is worth serious study. The teaching advice and lesson plans for advanced epeeists called upon to teach at times is also a useful review for experienced epee coaches. Deladrier was the fencing master at the US Naval Academy.

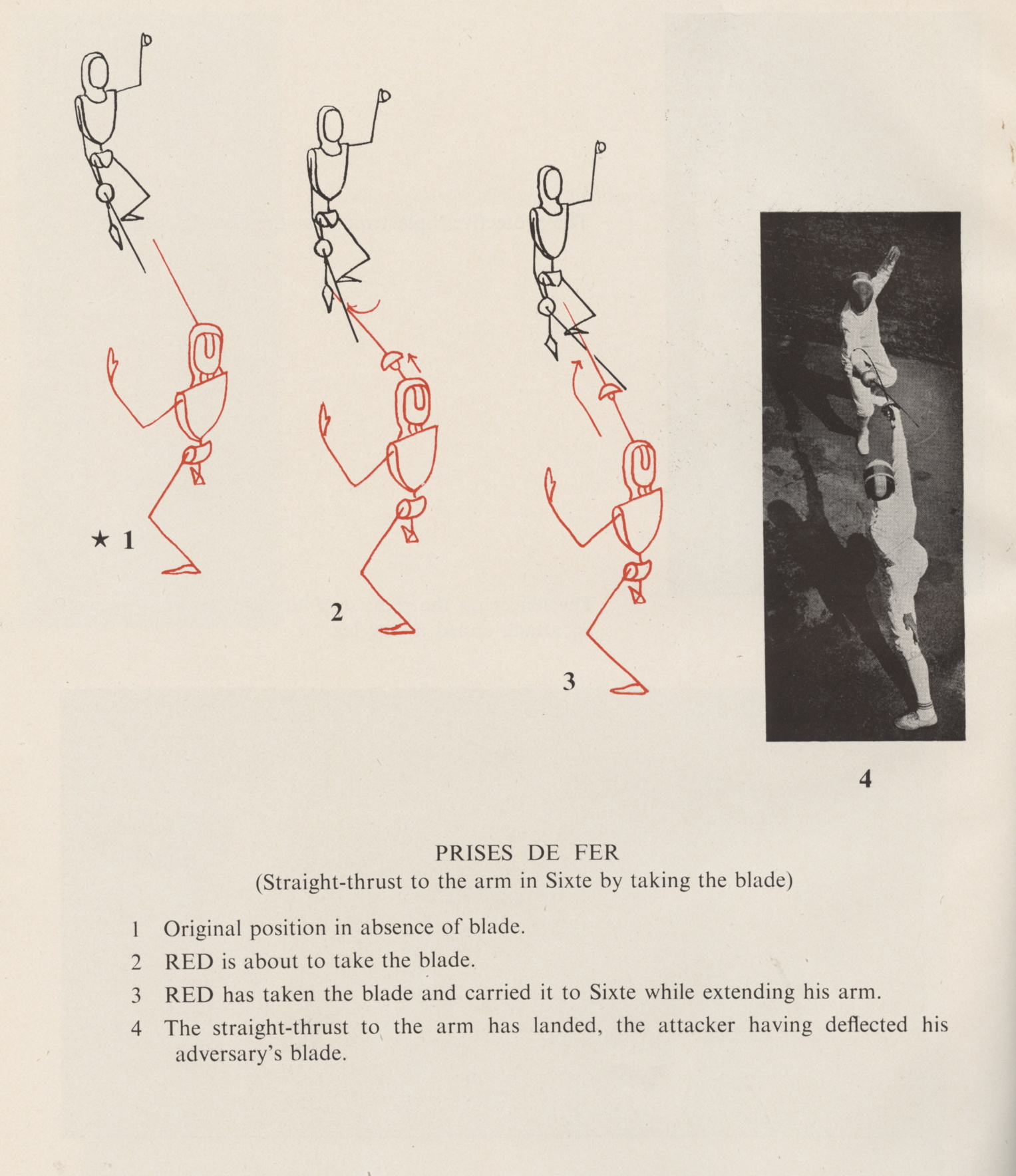

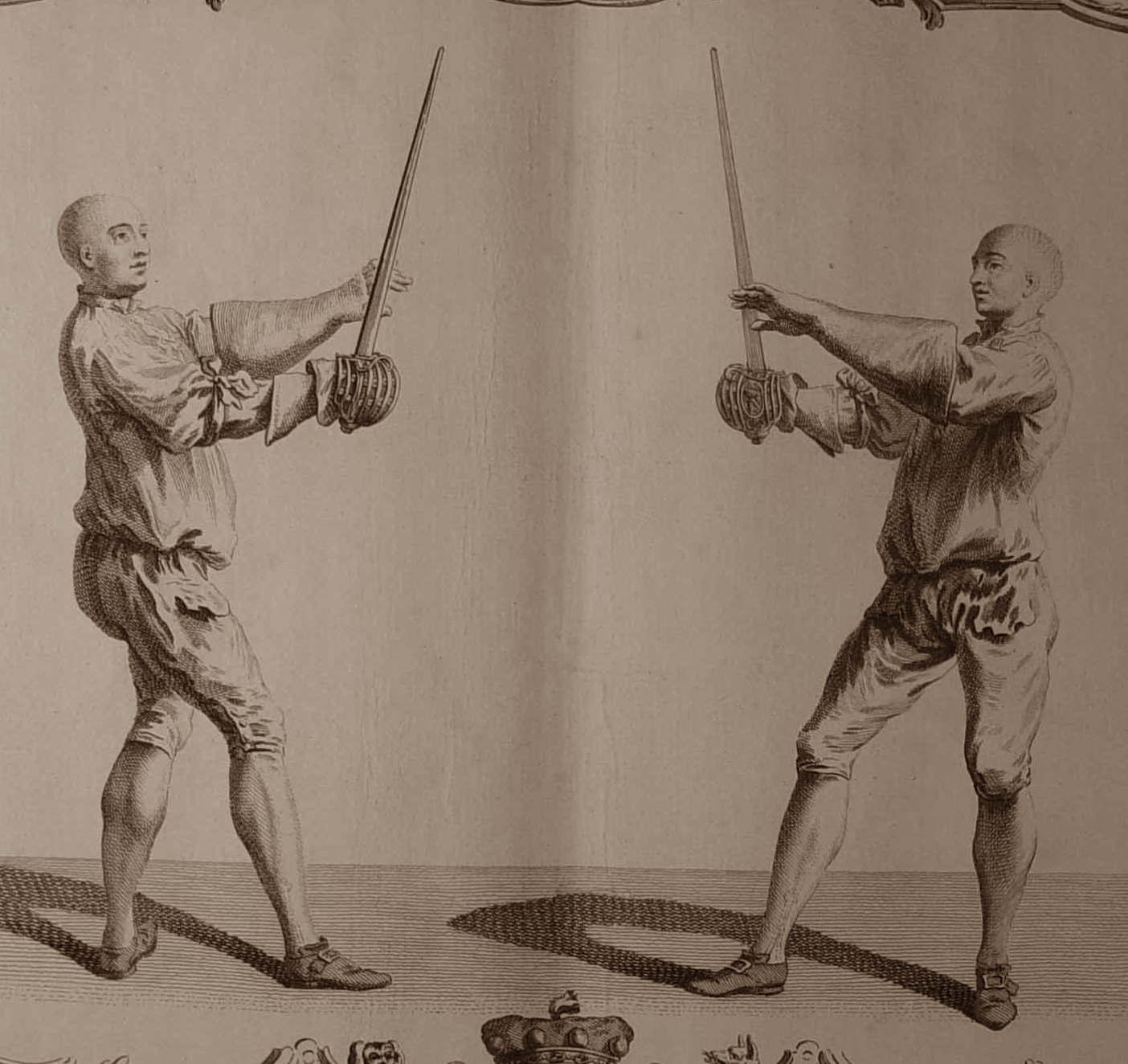

“Prises de Fer” from Fencing Technique in Pictures.

Fencing Technique in Pictures, 1955, edited by C-L. de Beaumont, assisted by Roger Crosnier, with contributors Léon Bertrand, Bela Balogh, and Raymond Paul. Basic foil, epee, and saber instruction by a who’s who of UK fencing masters of the past century, in line drawings and photographs, the former of which look a bit like the robots in the old comic book, Magnus, Robot Killer. Useful information, still applicable today. The book is one of three on this page attempting to show action in sequence in more than two or three steps using photographs or illustrations, the other two being Bertrand and Anderson. I suspect the format of the images and size and color of the book may have influenced Bac Tau’s excellent edition (see below) which in some ways might be an homage. “Dedicated by permission to The Rt. Hon. Sir WINSTON CHURCHILL K. G., O. M., C. H., M. P. First Honorary President of The Amateur Fencing Association.”

Fencing: Ancient Art and Modern Sport by C-L de Beaumont, 1960, 1970, revised edition 1978. Solid “classical” text on electric foil and epee, and dry saber by a noted British master and Olympic fencer. Excellent, perhaps best anywhere, description of the character and characteristics of epee fencing (de Beaumont was an epeeist). Good chapters on tactics and training.

Epee points. The “pineapple” tip, an electrical intermediary between the bottom left and (modern) right, is missing. From Cléry.

Escrime by Raoul Cléry, 1965. A thorough, practical text, absolutely one of the best, by one of the great French masters. Highly recommended. The epitome of the French school in foil and epee, but the saber is Hungarian and is so noted.

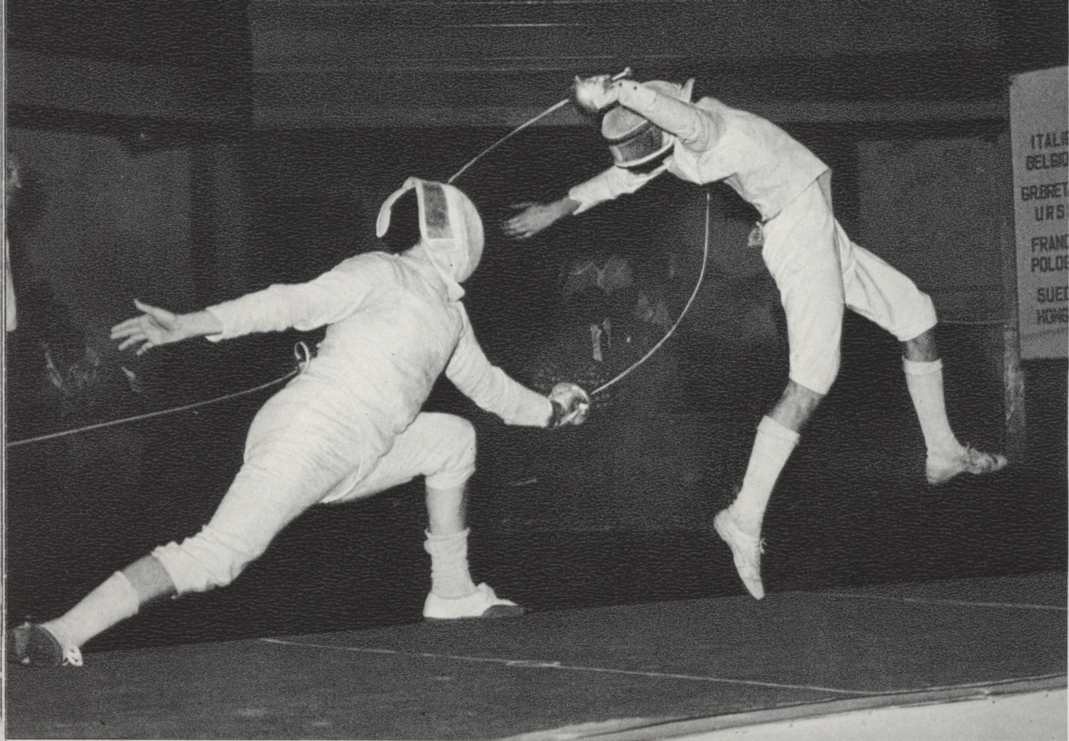

Athleticism in epee roughly half a century ago, hardly a new thing. From Mangiarrotti.

La Vera Scherma by Edoardo Mangiarotti and Aldo Cerchiari, 1966. A very useful book for all three weapons, although I’m naturally more disposed to its epee section, particularly given Mangiarotti’s fame in the spada. Exceptionally well-illustrated. In Italian, and the modern classical Italian school, of course. An excellent beginning to intermediate text on all three weapons. One of the virtues of this book are photographs of technique in action, showing what fencing actions actually look like as performed by elite fencers. Most fencing books use posed photographs or otherwise idealistic illustrations, providing elevated expectations of the often unattainable except at slow speed with a conforming partner. There is nothing wrong with illustrating the ideal, providing it is pointed out that it is exactly that, an ideal, seldom to be seen in practice even by elite fencers. The book also includes line drawings of ideal technique.

Modern Fencing: Foil, Epee, and Saber by Michel Alaux, 1975. A thorough introduction to all three weapons by one of the great French masters who taught in the US. Short but good sections on bouting tactics, lessons, and conditioning. Excellent beginning text for the novice fencer. The French school, of course.

Fencing: The Modern International Style by Istvan Lukovich, 1975, 1986. By the author of the noted Electric Foil Fencing. Excellent if brief epee section, very useful to both epeeists and their teachers in that it covers and explains most of what most epeeists will ever need to know. The Hungarian school. Highly recommended for all three weapons.

L’Escrime by Jacques Donnadieu, Christian Noël, and Jean-Marie Safra, 1978. Solid introductory to intermediate text, quite well-illustrated with many photographs of fencing technique, including of technique in competitive action. I’m also somewhat partial to the book given that its images, taken as they were at the time I began fencing, are nostalgic.

Fencing: Techniques of Foil, Epee and Sabre by Brian Pitman, 1988. Solid beginning to intermediate text.

Fencing by Bac H. Tau, 1994[?]. Includes thorough sections on training, tactics, and weapon repair. Excellent section on physical training for fencing, along with other highly useful appendices. Deserves far more attention than it has received. Highly recommended. The book size, cover color, design, and illustrations may have been influenced by–in homage to?–Fencing Technique in Pictures, edited by C – L. de Beaumont, 1955.

Foil, Saber, and Épée Fencing by Maxwell R. Garret, Emmanuil G. Kaidanov, and Gil A. Pezza, 1994. A very useful beginning to intermediate text.

Fencing: What a Sportsman Should Know About Technique and Tactics by David A. Tyshler and Gennady D. Tyshler, 1995. Excellent information but an at times poor translation from Russian. Supplement with the Tyshler DVDs (available from many fencing equipment suppliers), or better yet, simply refer to the DVDs. David Tyshler was a Russian master and Olympic and world championship medalist; Gennady Tyshler is a leading Russian master. Quite a few excellent fencing and teaching materials produced by the Tyshler’s are now available online.

The Complete Guide to Fencing, edited by Berndt Barth and Emil Beck, 2007. The German school. A thorough, up-to-date text. Good sections on theory, performance, and athletic training (with a useful emphasis on high rep exercises). Good epee section, much derived from the highly successful Tauberbischofsheim school of epee founded by the largely self-taught Emil Beck.

Modern Foil

The technique described in many of the books in this section is based on the 20th century rule that a foil attack consists either of a fully extended arm with point threatening—aimed at, that is—the valid target, or the later rule which permitted an extending arm with point threatening relaxed, and correctly so, in order to accommodate the highly useful and historically proven progressive attack. These rules—even the original requirement of an extended arm before the lunge, which is not ideal in combat— were rooted in dueling practice and therefore made more sense than the modern interpretation of an attack which is, frankly, often indecipherable and which under the original conventions of attack, not to mention in engagements with “sharps,” would be easily invalidated by a counter-attack. In other words, an attack should not consist of a bent, non-extending arm at any point, especially one with the point aimed at something other than the valid target. Attacks in invitation or otherwise with a bent non-extending arm are quite simply not in the spirit of staying alive. In other words, were the swords pointed, the modern attack would be simply suicidal. Unfortunately, right-of-way in foil and saber have abandoned this principal, permitting attacks with a bent-arm and the point well out-of-line. Put more simply, fence epee until foil and saber are fixed—if ever they are.

Fencing with the Foil by Roger Crosnier, 1955. One of the best expositions of modern classical foil of the French school ever written in English. Excellent explanations of practical theory, including on tempo and the progressive attack. Frankly, excellent throughout. Epeeists should read it together with Crosnier’s epee text, foilists together with Lukovich’s foil text.

Foil Fencing by Muriel Bower [Muriel Taitt], 1966 et al. Numerous editions, prefer the latest (1996, Muriel Taitt). Solid beginning foil text, used over the four decades by thousands of beginning fencers, including in 1977 by the compiler of this list of books in a beginning class taught by Dr. Francis Zold. Or at least I think it was this text. Perhaps it was Curry’s instead? The second editon of Bower’s version includes as co-author Torao Mori–a noted competitive fencer and fencing master–who took over the Joseph Vince Co. fencing supplier on Crenshaw Blvd (and where I purchased my first fencing mask, jacket, and glove in 1977).

Fencing by Nancy L. Curry, 1969. Solid beginning foil text although dated in terms of “modern” foil technique and rules. Even so, a good text on core technique. The book is clearly intended to accompany a college-level beginning fencing class and here it succeeds, describing in basic terms the fundamentals that can be covered in a single semester. As with a few other texts, it has useful images of fencing technique taken from above in order to show correct relationships. Nit-picking here: in the acknowledgements, a reference to the famous Castello fencing supplier is written as Costello, a typo and surely not a hat tip to Abbott and Lou…

All About Fencing: An Introduction to the Foil by Bob Anderson, 1970, 2nd printing 1973. The book is unique in that the reader can, by flipping pages, see properly executed technique, and in a manner superior even to much of the modern fencing video available. There is a hint of two of sexism common to the era—Anderson states that only men can cope with the epee and sabre, for example, which is nonsense—, but few fencing books of the first seven or eight decades of the 20th century do not take such a view. Some might disagree with some of his brief fencing history as well, but the history in many fencing books is open for debate, based as it often is on common understanding as opposed to rigorous analysis.

Anderson was a British Olympic fencer and Olympic coach who became Hollywood’s leading swordplay choreographer, following in the footsteps of Fred Cavens and Ralph Faulkner. The fencing in Star Wars, The Princess Bride, and Alatriste are but three of his many film works. (His book is also one of the first two books on fencing the compiler of this list ever read. In fact, the book was in the Mount Miguel HS library—seldom anymore will you find fencing books in high school libraries.) Mr. Anderson died on January 1, 2012, and was inexplicably and inexcusably snubbed by both the 2012 and 2013 Oscars during the In Memoriam segment.

Electric Foil Fencing by Istvan Lukovich, 1971, 1998. Perhaps the most thorough electrical foil text, with excellent sections on fencing theory and requirements. Valuable even today, in spite of being written and published prior to the modern debasement of right-of-way conventions (i.e. attacks in invitation or “bent arm” attacks legitimized), although foil and saber were already inclining in this direction when Lukovich wrote his book.

Foil and The Revised Foil by Charles Selberg, 1975 and 1993 respectively. Thorough and very useful, with a good section on tactics. Highly recommended, but prefer the 1993 Revised Foil. Selberg also produced an extensive selection of instructional videos. Now on DVD, they are available from Selberg Fencing at http://www.selbergfencing.com/.

Basic Foil Fencing by Charles Simonian, 2005. A solid introductory text.

Foil Lessons With Victor by David A. Littell, 1994. A twenty-three page foil monograph far more useful than its brevity might suggest. It’s based on the author’s lessons from fencing master Victor Bukov. Useful in all three weapons, it presents a variety of tactical methods of attack, heavily distance-based. Readers familiar with Hungarian theory and practice (and thereby Russian and general East European) will recognize the descriptions.

“Modern” Saber

Modern Sabre Methodology by Zoltán Beke and József Polgár, 1963. Translated from the Hungarian. Not “modern” in the sense of the most recent form of saber fencing, but “modern” in the sense of twentieth century Hungarian saber before saber’s debasement via the electrical scoring system and the degeneration of the interpretation of right-of-way. Worth acquiring if you can find an affordable copy, but if you do it will likely be by accident, unfortunately. Mine was. A very thorough exposition of every technique in the Hungarian saber repertoire. Not for beginners! One of my favorite passages is its excellent, simple definition of tempo, along with the very useful discussion following, all suitable to all three weapons—or to all swords in all places in all eras, in fact. It is also, from a historical perspective, easy to see how Hungarian saber influenced Hungarian epee, and therefore modern epee.

Fencing With the Saber by Roger Crosnier, 1965. Excellent, thorough work on “Hungarian” saber, second only to that of Beke and Polgár above. A suitable companion to Prof. Crosnier’s works on foil and epee. Note, however, that the terminology and categorization of technique is of the classical French school, not the Hungarian. The fundamentals are still useful today. Naturally, Prof. Crosnier does not permit the attack with the arm in invitation or otherwise bent…

Modern Saber Fencing by Zbigniew Borysiuk, 2009. Only if the modern “weapon” known as electric saber appeals to you. Still, a very good book, and the only thorough one on the subject in print in English. Unintelligible conventions plus attacks with the unextending arm held low in invitation while leaving the body nakedly exposed plus awkwardly cramped footwork plus hitting with the flat of the blade do not saber fencing make. The flat merely chastises: it’s the edge that cuts. The rest is simply too tiresome to debate.

The Cléry and Lukovich titles in the “Epee, Foil, and Saber” section have excellent instruction on Hungarian saber. Cléry also includes some detailed history of the origin of the Hungarian school. The Beck/Barth text includes excellent information on modern post-Hungarian saber. The famous Hungarian saber technique was destroyed principally by the electrification of saber, said by knowledgeable world class fencers and FIE sources to have been a compound decision based on the likelihood that the obvious flaws in electric saber would permit a less strict technique, particularly when aided by a debasement of right-of-way, and would thereby open international saber medals to more than the handful countries with the critical mass of elite saber coaches and sabreurs able to master in-depth the clear, clean technical repertoire of the Hungarian weapon; such technique was mandatory for correct judging.

For half a century Hungary reigned over twentieth century saber, and maintained a strong grip on it even after a number of sabreurs defected during the Melbourne Olympic Games in response to the 1956 Hungarian uprising against the Soviet Union. Recent US gains in modern electrical saber were based in part on the early willingness of US coaches to embrace the new “weapon,” while some of their European counterparts, who had previously excelled in saber, attempted to continue the use of traditional Hungarian technique.

Theory, Teaching, and Training

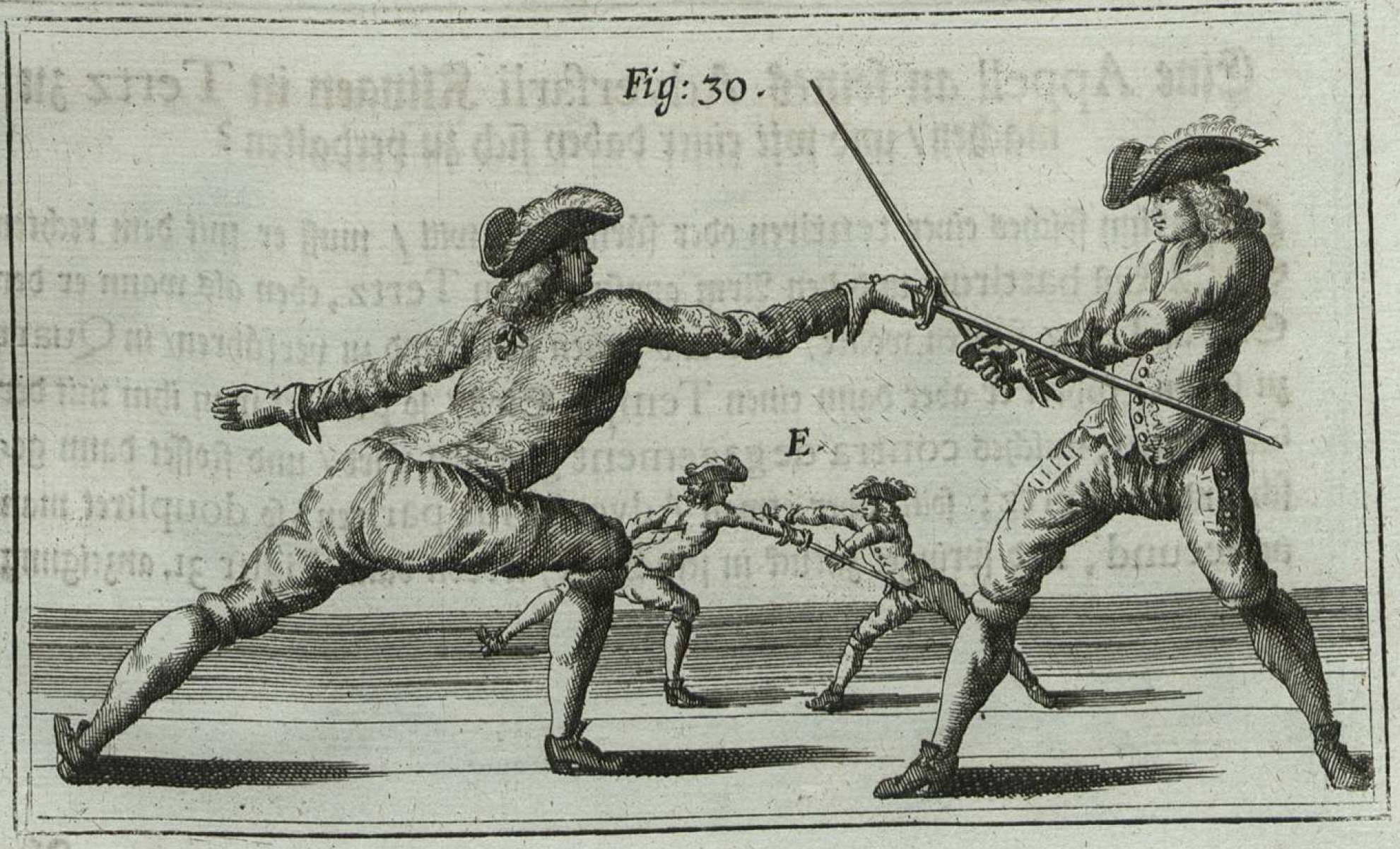

From Szabo.

Fencing and the Master by László Szabó, 1977, 1997. Forward by Dr. Eugene Hamori, a student of Szabó’s (and my second fencing master), in the 1997 edition. The best book ever written on the subject of teaching fencing: the fencing coach’s vade-mecum. Highly recommended. Excellent material on theory and other aspects of fencing, besides the practical. Intermediate to advanced fencers will also find it useful, in particular for its sections on tactics, preparation, drilling, and stealing distance. Szabó, who trained a number of Hungarian champions, was one of Italo Santelli’s three protégés and a close friend of Dr. Francis Zold, my first fencing master.

László Duronelli and Lajos Csiszar were the other two Santelli protégés. Csiszar was master for many years at the University of Pennsylvania after emigrating to the US. Among his students were Dr. Eugene Hamori and Roger Jones, the latter of whom one day contacted me about writing a review of one of my books; during our conversation we realized we had the same ultimate fencing roots and identical views, therefore quite understandably, on honor in fencing. Duronelli was master for many years at the fencing salle at Semmelweis High School, run by Semmelweis University, in Budapest. This delightfully old school salle, which has produced many champions, is still in existence, with László Szepesi, who helped bring saber gold to France, as its current master. Eugene Hamori along with Krisztina Nagy (a very talented fencer and master in both HEMA longsword and modern Olympic saber) escorted my wife and me on a visit to the salle not too long ago.

A Dictionary of Universally Used Fencing Terminology by William M. Gaugler, 1997. A well-researched fencing dictionary although it could have been even longer — but then, only fencing aficionados like myself might read it.

Escrime: Enseignement et entraînement by Daniel Popelin, 2002. In French. The theory and practice of teaching fencing and training fencers. Rather than use the typical pyramidal view of fencing from its base to its competitive elite at the point, M. Popelin suggests a truncated pyramid, whose range is from beginner to national level, to indicate the majority of fencers, and a cylinder on top of this to indicate international and aspiring-to-international fencers. He astutely notes that the majority of fencers do not seriously train to become elite fencers, for many reasons, and thus fencers should be trained differently according to their needs. In other words, the training of the “club” fencer, no matter how talented, should be different from that of the elite competitor. Or put another way, simply because a technique, classical or otherwise, is not used at the elite level is no reason for non-elite competitors to abandon it or, worse, never learn it.

Understanding Fencing by Zbigniew Czajkowski, 2005. Highly recommended for fencers and coaches interested in practical theory. Czajkowski is a leading Polish master whose students in all three weapons have earned gold at the Olympics and world championships.

One Touch at a Time by Aladar Kogler, 2005. The psychology and tactics of competitive fencing, by an Olympic fencing coach and noted sports psychologist. Recommended.

Theory, Methods and Exercises in Fencing by Ziemowit Wojciechowski, circa 1986. By a world-class fencer and master. Foil-based, but still an excellent book for fencers and coaches of all three weapons. Good information on evaluating and dealing with an opponent’s tactical style, especially in foil, although, again, still useful in epee and saber.

See also Joseph Roland, The Amateur of Fencing, in the “Historical Fencing” section below.

“Classical Fencing”

(Modern Non- Electrical Technique)

Some of the books below (Barbasetti, Gaugler) use one of the several classical Italian parrying systems and numberings, as opposed to the French or modified French systems and numbering preferred by most teachers today. (There are also several French-based numbering systems, each differing slightly in the naming of a parry or two, or in the use of a parry, for what it’s worth.) All of the books below are useful to the modern electrical game, epee particularly, and to foil and saber at their fundamental level. At some point foil and saber may return to a more classical standing, rather than their present sport-dominated extreme artificiality, notwithstanding that foil has always been highly artificial, at least for the past 150 to 200 years, and moderately artificial prior to that. Even in the heyday of dueling there was a distinction between “school play” and “fencing with sharps.” See also the texts listed in the “Epee de Combat” section.

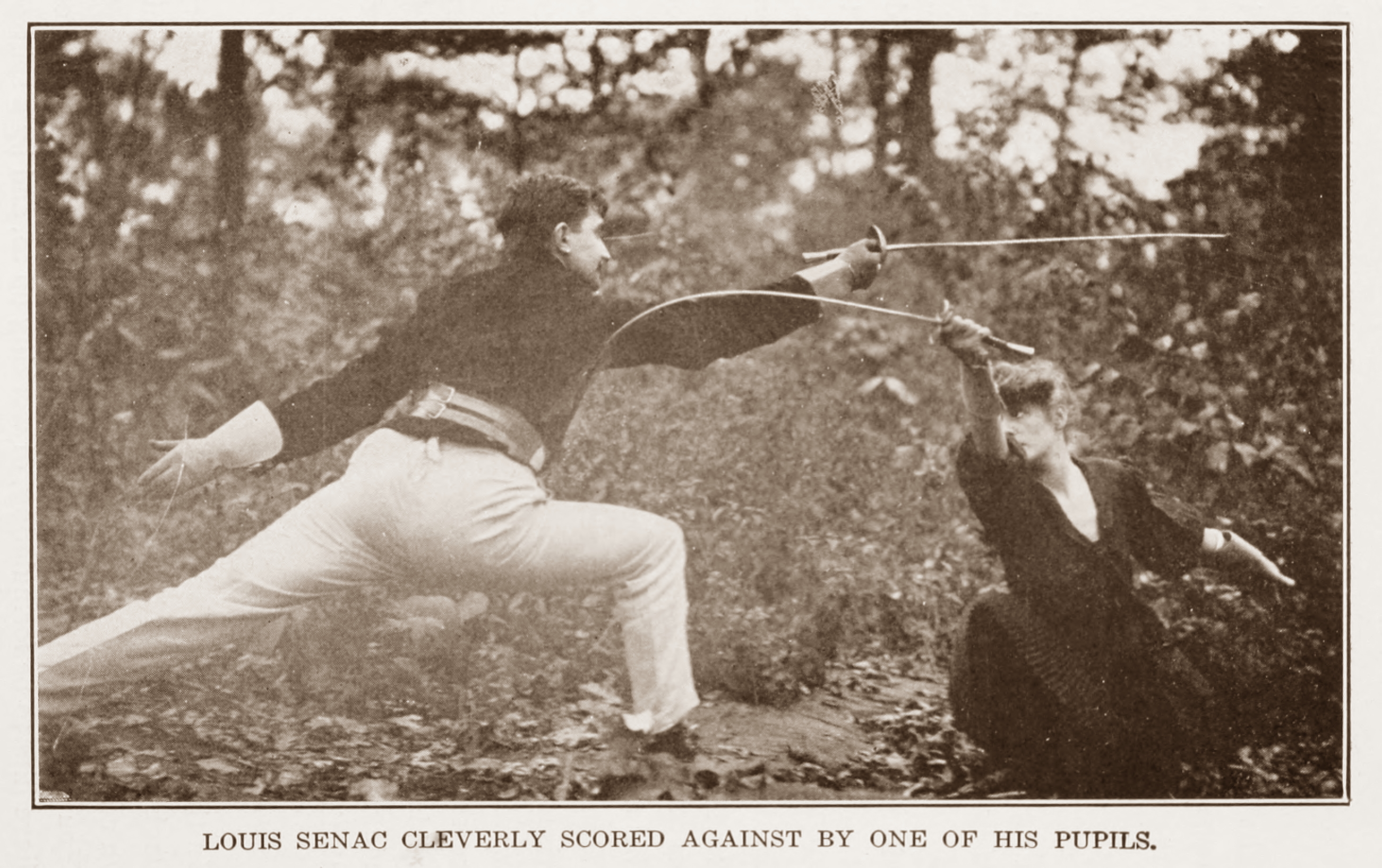

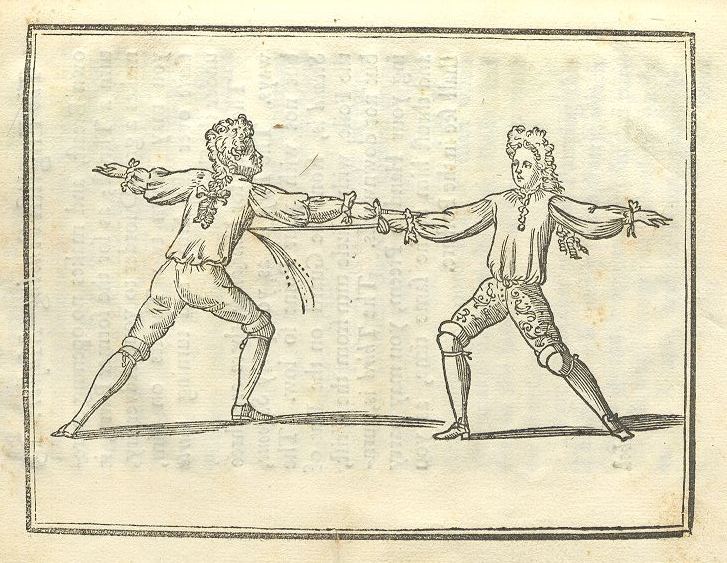

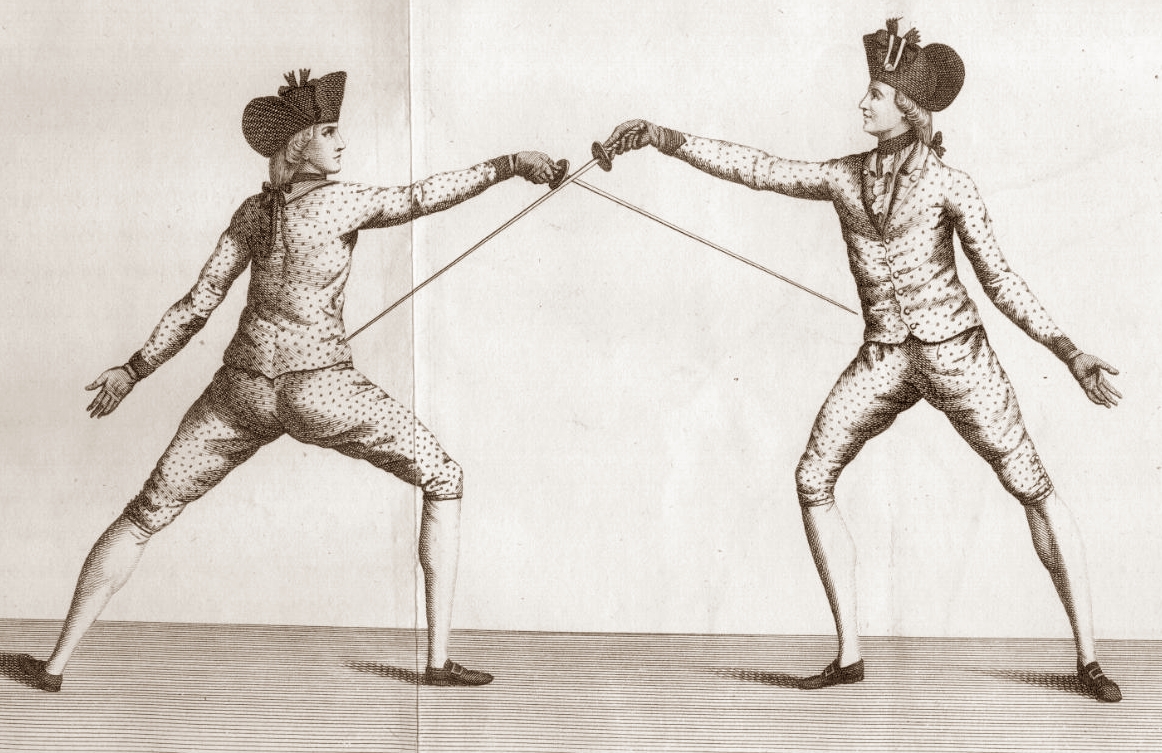

At the right, a beautifully executed (or more likely posed) lunge inward off the line: the Italian intagliata although it is not so-named in the book. Odd that a book that extols the French school so much would demonstrate a technique considered largely Italian at the time. From The Art of Foil by Louis and Regis Senac.

The Art of Fencing by Louis and Regis Senac, with a section on saber by Edward Breck, 1904 (hardcover), also 1915 & 1936 (softcovers, with foil and saber by Breck). Part of the Spalding Athletic Library, the book is particularly useful to fencing historians as it covers a transition period in modern fencing, has illustrations of clearly expert women fencers (unfortunately unidentified), has lengthy fencing equipment adds (1905), shorter equipment ads (1915), and the 1905 Amateur Fencing League of America fencing competition rules (1915, 1936). The book’s downside–but only occasional–is its excessively evangelical attitude in promoting the French school, an attidtude associated with patronizing and common-at-the-time claims that one must be an overly-muscular athlete to fence well in the “inferior” Italian school. Blame the psychological reaction of inferiority by spindly and otherwise unathletic French fencers to the hyper-muscular Italian swordsman Eugenio Pini for this. One can also be lean and still very strong, as with the whipcord muscles of some of Rafael Sabatini’s heroes, a physical type well-suited to fencing and found in reality as often as in fiction. To my mind, there is no excuse, other than long-term injury or disease, not to be fit: with strong muscles, good flexibility, and excellent aerobic and anaerobic endurance. Although the book nobly promotes women’s fencing and notes that at least one woman fencer was more than a match for any man, it does recommend fencing to women in part because it “reduces surplus adipose tissue, making their figures trim and comely, rounds their muscles, develops their busts,” &c. Perhaps this was mere marketing and not sincerely-held chauvinism.

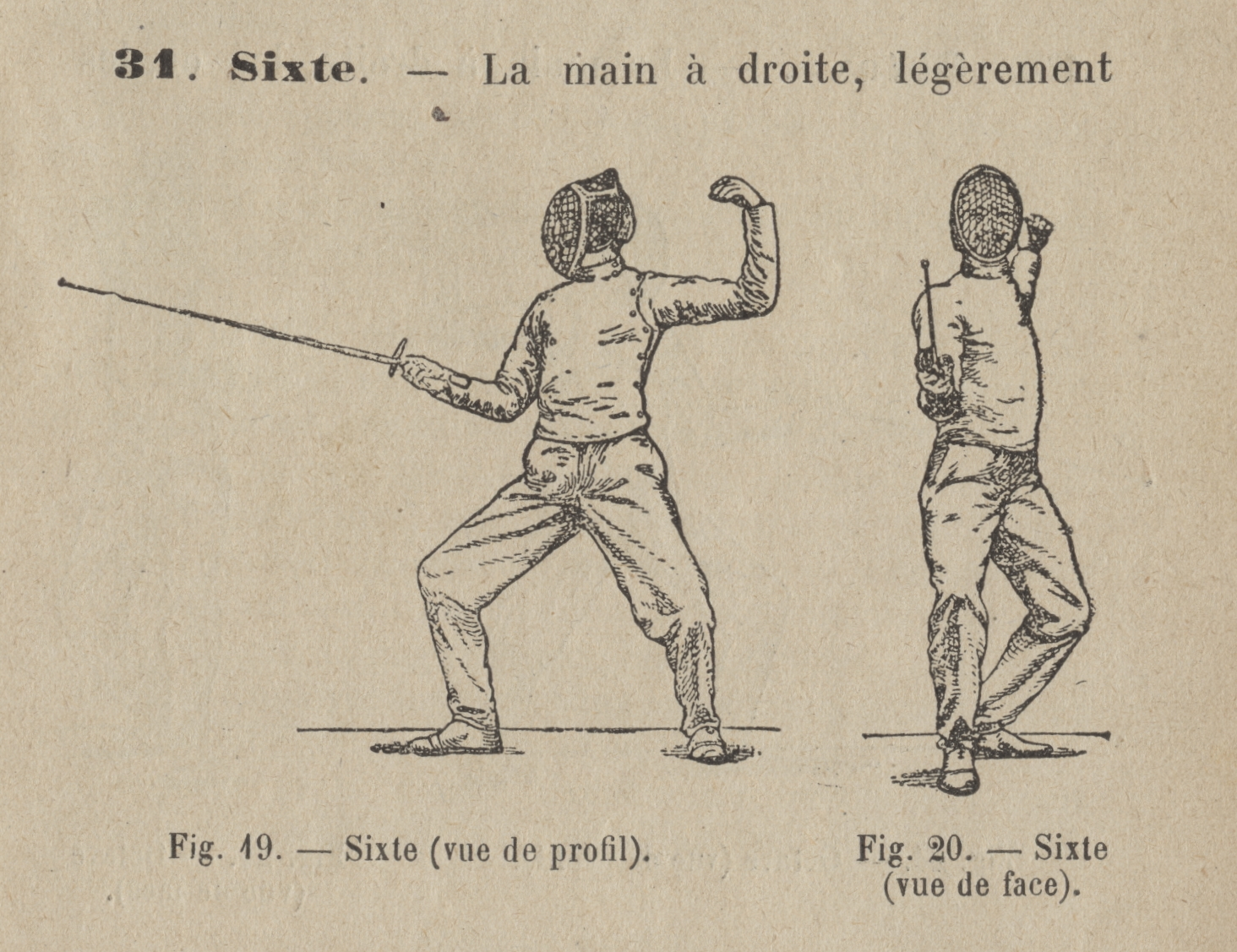

Sixte en garde from the Réglement d’Escrime.

Réglement d’Escrime by the Ministère de la Guerre, France, 1909 and other editions. A short treatise on foil fencing for the French military that provides a detailed look at the classical French school. Useful for classical fencers and historians, and, frankly, any fencers interested in French technique given that it remains sound today, at least as a foundation. Oddly, one would have expected the French military to have adopted the new epee technique rather than foil at this time, and even more so, would have emphasised the saber instead of either, given that it was still in use as a practical military arm at the time.

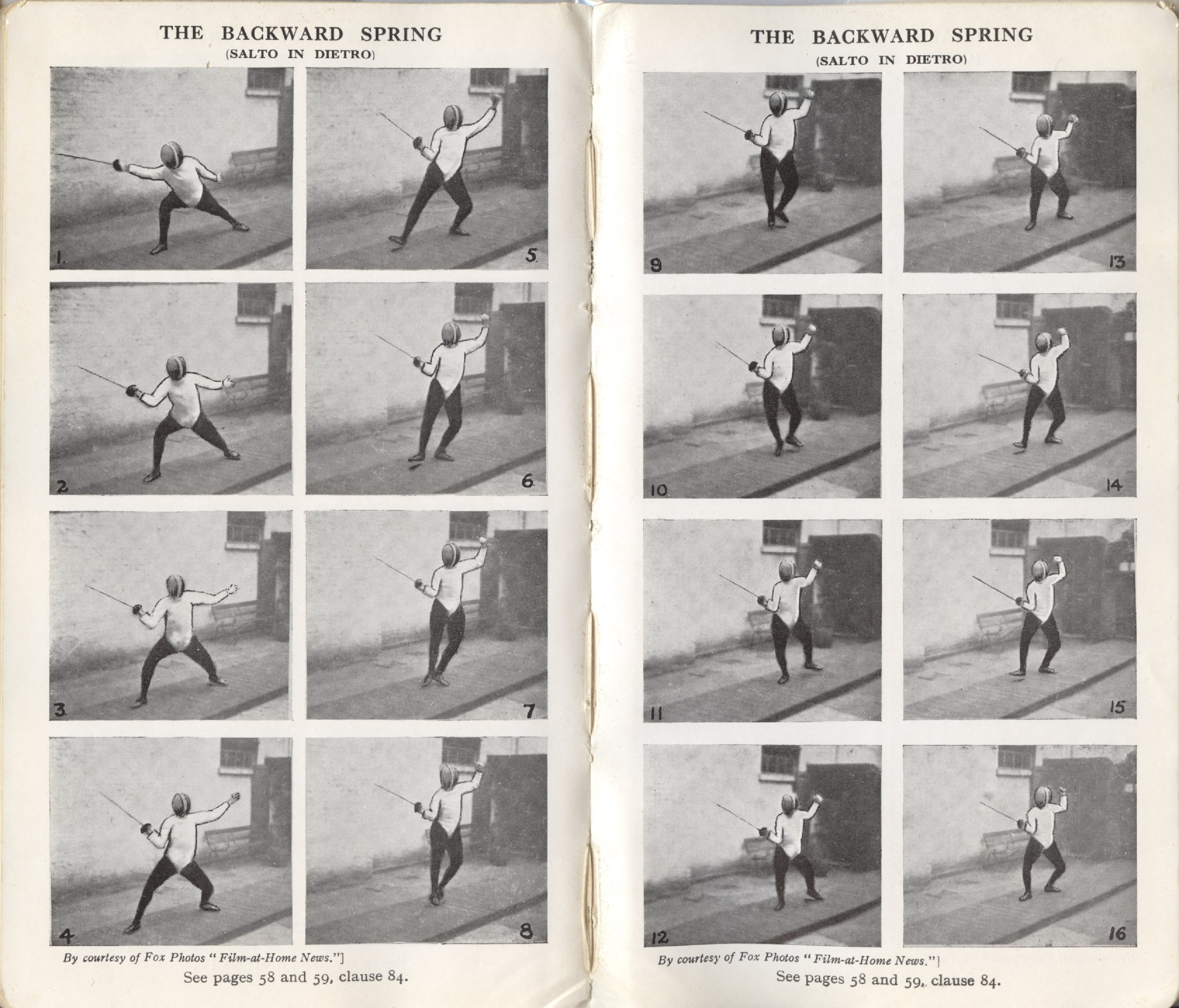

From Bertrand. The backward spring was used to great effect by Edoardo Mangiarotti, although as an epeeist he tended to spring back into a rassemblement with a straight-arm counter-attack, not a parry or en garde.

The Fencer’s Companion by Léon Bertrand, 1934 to 1958 and possibly later. A delightful little book, hardcover but pocket-sized, with enough information on all three weapons to substantially educate fencers from novice to intermediate-advanced, with fundamental lessons required at all levels of fencing. The book also includes useful advice on teaching fencing. Prof. Bertrand, son and grandson of famous British fencing masters of French descent, was one of the most influential masters in the history of modern fencing in the UK.

Among Prof. Bertrand’s useful advice is to learn to fence from the beginning with both hands, starting with the weak hand first for balance. It’s advice unlikely to be followed often but it has excellent virtues, and will likely be the subject of a blog post one of these days. Twenty-five years ago I began learning to fence left-handed in order to give left-handed lessons as well as right. Two years ago I seriously incorporated left-handed footwork, drills, and fencing into my regimen, equal those of my right-handed, with quite useful results. Prof. Bertrand also has advice for fencing against classical Italian fencers, in which the counter-quarte and Italian prime (a high septime) dominate. (Note for readers of Imre Vass: his “destructing parries” in quarte and septime correspond to–are equivalent to–these two classical Italian parries that in combination “cut the line” or “destroy” feint attacks in the high line and will parry high-low and low-high feint attacks in the inside line.)

I’d not be surprised to find that The Fencer’s Companion influenced All About Fencing: An Introduction to the Foil by Bob Anderson, in particular the images of technique in action. Whereas Prof. Bertrand includes a series of photos depicting various actions as shown above, Anderson took this a step further so that by flipping pages the reader can see the technique in action, similar to a primitive film. See also Bob Anderson’s book on this page.

The Book of Fencing by Eleanor Baldwin Cass, 1930. The book is particularly noteworthy as it was, and remains, one of only a handful of fencing texts written by a woman, even including modern texts. Ms. Cass was an American, and the book was, not surprisingly, published in Boston, birthplace both of conservative American Puritanism as well as liberal progressive thought. The epee section is sparse, as is often the case with many three-weapon texts, but the foil section is classically thorough. The book is also a great source on much of the fencing history of the day, and thus quite useful to the fencing historian.

The Art of the Foil by Luigi Barbasetti, 1932. The Italian foil. Includes a succinct but thorough history of fencing, a good section on tactics, and a glossary of fencing terms in English, French, Italian, and German. A useful book for epeeists as well. Barbasetti was one of several Italian fencing masters who carried Italian technique to Hungary and Austria, including to the Austro-Hungarian Normal Military Fencing School of Wiener-Neustadt in 1895 where he re-organized it. (Alfred Tusnady-Tschurl, one of my “fencing grandfathers”—the fencing masters of my own fencing masters—was a graduate and had studied under Barbasetti.) Italo Santelli was the most notable of these Italian immigrant masters. Santelli famously said that fencing is something you do, not something you write about—thus there is no book by Santelli in this list.

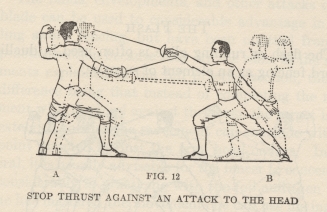

Castello, no comment needed other than “Don’t miss with your stop thrust!” This type of angular counter-attack was popular in sport epee but was not recommended in dueling, as it would in all likelihood not arrest the attack. “I hit him in the wrist but he put my eye out,” is not a desired outcome in a duel.

The Theory and Practice of Fencing by Julio Martinez Castelló, 1933, & Theory of Fencing, 1931. One of my favorite dozen or so fencing books. The author was trained in the early 20th century Spanish school, which was based on the best of the French and Italian, including a modified modified French grip that gave it the (theoretical) point control of the French grip with the strength of the Italian grip. (This grip is illegal in modern competition, although a pistol grip variation without an external weighted pommel exists that is legal, if you can find it.) The Neapolitan Italians were the first to formally attempt to combine the French and Italian schools on any scale, followed by the Spanish and, via the Italians, the Hungarians, although fencing “schools” have always adopted technique from each other and adapted it to their own methods. However, in both editions the author notes that the book, which he wrote to help “young men and women in the many schools and colleges” in the US, including those without a teacher, is not based entirely on any particular system, although he says the foil is mostly French, the saber Italian, and the duelling sword (epee) from his own experience.

The author notes that at the time he wrote his book the French school predominated in the US, and this remained largely true at least until the 1970s, in foil and epee especially, in spite of an influx of elite Hungarians in the 50s and 60s. (I was often told in the late 70s and early 80s that I fenced epee like a pentathlete, rather than conventionally, French, that is: in fact, I fenced like a Hungarian, although notably my lessons from two Hungarian masters and one French master–the famous Michel Sebastiani, French-Corsican, and a former pentathlete–were seamless and very similar.) Saber in the US was by the 70s largely Hungarian, at least among the best sabreurs. Castelló also writes that the predominant saber school circa 1930 was Italian, but in fact by then the Hungarian school, based on the Italian but modified to suit Hungarian attributes, was dominant. But this is a quibble, yet I’ll add one more: Castelló repeats the canard about the saber target being limited from the waist up because it was a cavalry weapon, i.e. one didn’t hit the horse. This is arrant nonsense, still repeated today. The target in saber is based on an old Italian rule that limited the target to the area above the waist in order to protect a duelist’s manhood. This is noted in numerous late 19th century Italian texts.

Castelló had also self-published a smaller volume, Theory of Fencing, in 1931. Copies could be ordered from the author himself for $2. The more detailed 1933 version was released by noted publishing house Charles Scribner’s & Sons. Both books–the later book is simply an expansion of the first in both text and illustration–are excellent sources of fundamental fencing theory and technique, knowledge often far too lacking in many fencers today. Castelló included an excellent description of the two most classical epee styles–“straight arm” and “bent arm”–and associated technique and tactics. (See Lidstone’s later edition above for others.)

Among Castelló’s students was Joseph Velarde, the West Point Military Academy fencing master whose stand against racial discrimination opened US collegiate fencing competition to black fencers. By coincidence I once worked with Velarde’s son, a former US Marine Corps officer, many years ago. A decade before that I had fenced with and competed against the founders of the old M.A.R.S. Fencing Club at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, most of whom were among the Apollo engineers who put humankind on the Moon. (The fourth was and is a brilliant Byzantine iconographer.) One of these veritable musketeers, Joe Dabbs, who has since passed away, had trained for years under Velarde. I have remained friends with all of these old M.A.R.S. fencers for almost forty-five years, and most were active fencers until recently as age and old injuries restrained them, although I still fence with one of them regularly (Elias Katsaros, with French grips and true “hit and not get hit” dueling practice only!). John Jordan and Donny Philips—the other two members of the Four Musketeers—are also still with us.

Barbasetti, a filo (bind) thrust in tierce. Note that the Italian bind thrust or filo is a thrust with strong pressure in the same line: it is neither a French liement nor, arguably, quite equivalent to a pression or graze, for it is generally delivered with more strength than the latter. This thrust is commonly made today in sixte. The filo thrust in the high outside line has been a staple of dueling sword technique for centuries, given its relative safety.

The Art of the Sabre and the Epee by Luigi Barbasetti, 1936. By one of the great early twentieth century masters. The epee section is quite sparse, and refers the student to the foil for much technique, a quite common practice in many of the Italian schools, given the similarity in technique and practice between the two weapons. Castello’s book (see above) has a far more thorough epee section.

From Fencing Comprehensive by Félix Gravé, 1934.

Fencing Comprehensive by Félix Gravé, 1934. A delightful and, too my mind, too short fencing treatise covering foil and epee, filled with pithy fencing wisdom that has never been out-of-date. The author’s general observations are also noteworthy. For example, the truly classical fencer in form and technique is born, not made. (Not to worry, those of you in the majority who weren’t born to fit into the classical mold–even in the days of “classical fencing” such fencers were rare, and one need not fit this mold in order to be a great fencer. Anyone who tells you otherwise is ignorant and probably, to quote The Princess Bride, selling something.) Gravé has good advice for teaching, on dealing with some of the more common types of fencer, on tactics in general, and for conducting a duel. For the fencing historian, he has several drawings of period fencing grips, the French interchangeable epee system (l’épée démontable), various guards (coquilles), pommels, points d’arrêts, the development of the fencing mask, &c. Interestingly and happily, he mentions women epeeists, and has an illustration of the clothing they should wear (“men’s,” basically) long before epee was permitted to women in competition, a fact that pleases me immensely.

On Fencing by Aldo Nadi, 1943, reprint 1994. A famous Italian fencer’s thoughts, pompous, patronizing, and otherwise, on technique and competition. For Nadi, there was only one correct way to fence: his. Held up as a god by many modern “classical fencers,” Nadi despised the French grip as much as many of the same “classical fencers” today despise the pistol grip and advocate the Italian and [Nadi-despised] French grips. Let no one claim that blind self-irony and hypocrisy, often humorous, even hilarious, never reigns among pseudo-experts, or for that matter, among quite a few true experts.

The Science of Fencing by William M. Gaugler, 1997. A thorough modern description of purely classical Italian foil, epee, and saber technique. Pedagogical, as one would expect, and almost old school military in its technical presentation. Professor Gaugler, a student of Aldo Nadi and other great classical Italian masters, passed away in 2011.

Fencing Tactics

Many books touch on fencing tactics, but to date I’ve found one devoted exclusively to the subject–and it’s one of the best books on the subject of fencing in general I’ve ever read.

Fencing Tactics by Percy E. Nobbs, 1936. By the 1908 Canadian Olympic Foil Medalist, the book is a delight to read and study, easily one of a handful of the most practical fencing books ever written, certainly one of my handful of favorites even if I don’t agree with everything–and is a book generally unknown to nearly all fencers these days. It is also one of only two books by Canadians on this list (see also Bac H. Tau), and both are outstanding. However, take heed: the book is based on classical notions of tempo and right-of-way, and in some ways is an exposition largely of how the author fenced (similar to the books of Nadi and Harmenberg, for example).

Mr. Nobbs covers tactics in depth, better explains the difference between the classical Italian (and by implication, Italo-Hungarian) school versus the French, discusses opposition thoroughly, points out how important footwork is to tactics, and captures well the spirit and practice of each of the three modern weapons. He also describes the difference between free fencing (loose play), competition fencing, and exhibition fencing–and particularly how one should fence and behave in each form. For example, the superior fencer should trade touches with the weaker in free fencing, rather than simply trying to hit as many times as possible.

Mr. Nobb’s discussion of opposition is quite useful, with educational observations on the role played by the bend in the blade as it hits, something that would not occur with real swords and their very stiff blades. This blade bending is less relevant today with electrical scoring in epee, but is still pertinent in the conventional weapons: for example, a counter-attack without priority but whose blade bends as it hits can help exclude the arriving valid attack. In other words, the valid attack might have arrived were the blade to remain straight. The book also describes useful footwork beyond the conventional advance, retreat, lunge, and recovery, most of which is seen today, but not all. We rarely see, for example, the stolen march (forward crossover, lunge) today, although I was in fact taught it decades ago. Still, some epeeists today occasionally use a crossover followed by a fleche, often as a suprise attack after the command “Fence!” is given. Nor do we see the reverse rassemblement (standing as in a rassemblement but by bringing the rear foot forward) to make a counter-attack, a practice once used in foil.