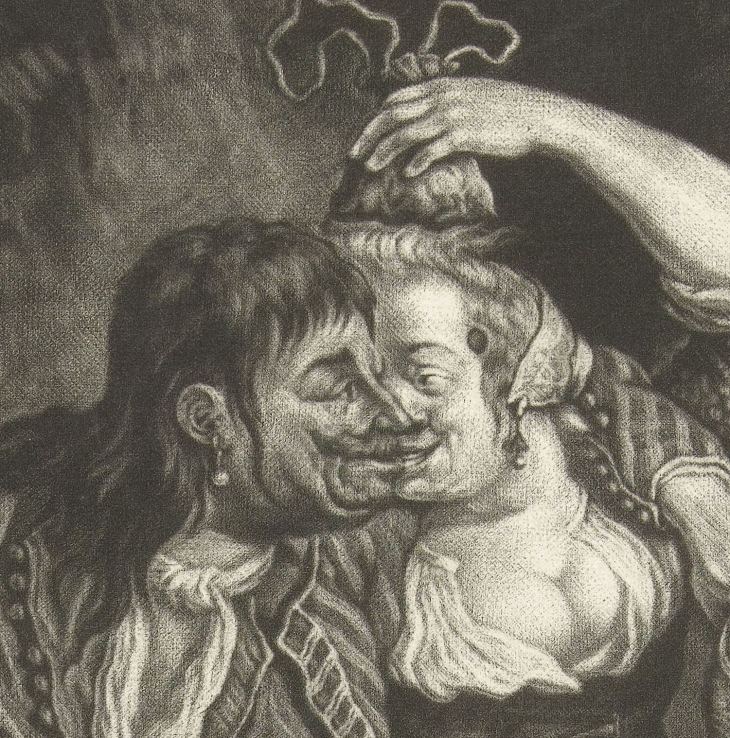

A Dutch seaman in Amsterdam dancing in celebration of the recapture of the city of Namur in September 1695. By Cornelis Dufart, 1695. Rijksmuseum.

Quite often today, reenactors, students of authentic pirate portrayals of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, aka the “Golden Age of Piracy,” and the makers of any television documentary or drama, or any film, about pirates who wants to be taken seriously will generally drop the pirate earrings and other pirate caricature, or at least minimize them. However, this practice, while avoiding “Hollywood” cliché, has one problem:

There were “Golden Age” seafarers who wore earrings.

The same goes for pirates of the “Golden Age” from circa 1655 to 1730.

As is the case with much of our perception of what is and is not correct and authentic about “pirates,” the myth or reality really applies much more broadly, to seafarers in general, and from there to the question of whether the myth or reality applies across the board to seafarers or only to a specific subset. For example, I was asked during a Reddit AMA a while back about the “crossing the line” ceremony originating from pirates. It doesn’t actually originate with sea thieves, but from mariners in general, unless all mariners were sea thieves. (Of course, some might argue that at least through the Middle Ages all seafarers were potential pirates…) Sea rovers may have practiced the various “crossing the line” ceremonies, just as seamen in general did, but it was foremost a maritime practice, not one specific to piracy. And I say various practices because there were different cultural practices, and different “lines” to cross as well.

So, put simply, were earrings a conventional part of pirate dress, or of maritime dress, in general during the period 1655 to 1730?

I’m going to keep the answer just as simple, for this is not the place to address the variety of seafarers, sea thieves, and their national and local customs and dress.

And the simple answer to both is…no.

Even so, many answers are really not so simple as they seem, and so it is with this one. There are three exceptions to the earring rule, and they apply not only to pirates and privateers, but to mariners in general.

“Matelot de Brabant / Brabantsche Schipper” by Bernard Picart, circa 1690 to circa 1733. Note the single pearl in the earring, apparently common among Dutch seamen. Rijksmuseum.

First is the Dutch exception. Earrings were common in the mid to late seventeenth century and into the eighteenth on many Dutch seafarers, as is clear by the several images I’ve posted here. The seaman in the image above wears an earring in the left ear, and the seamen in the Dufart images below mirror each other, one in the left, the other in the right. From the images it’s impossible to tell if the Dutchmen are wearing an earring on the other ear as well.

An earring or a wisp of hair? Dutch or possibly Norwegian seaman, late seventeenth century. Pas-keart van de Cust van Noorwegan by Joannes van Keulen.

So, if you want to be a sea rover and wear an earring and be historically accurate, be a Dutch pirate or privateer. That said, many serious pirate and privateer reenactors are opposed even to this out of concern that it gives the wrong impression: either in general, or because most of the early eighteenth century pirates were “Anglo-American,” or because there are only a “few” Dutch images of seafarers with earrings (although a “few” images would well suffice to support “facts” such reenactors are in favor of). For me, fact–truth–should outweigh this. First, given the large number of buccaneers or flibustiers of Dutch origin in the late seventeenth century, it would not be surprising to find earrings on some buccaneers. Second, not all of the early eighteenth century “Anglo-American” pirates were in fact British or Irish derived, and separate from them were French and Spanish pirates whose crews doubtless included some Dutch members.

Detail of a Dutch seaman in Amsterdam dancing with a woman in celebration of the recapture of the city of Namur in September 1695. By Cornelis Dufart, 1695. Rijksmuseum.

Dutch seaman with a rummer (Dutch roemer, a large drinking glass). Note the obvious earring. Jacob Gole, after Cornelis Dusart, after a fairly similar illustration lacking knife, pipe, and earring by Abraham Bloteling, 1670 – 1724. Using other artist’s and engraver’s illustrations as templates was common. Rijksmuseum.

Second is the fop exception. Through much of the seventeenth century, including the last quarter, and into the eighteenth century some French fops, and some English onesas well for they generally followed French fashion, were in the habit of wearing an earring, perhaps even one in each ear. The common assumption is that men’s earrings in England and Scotland went out of fashion after the death of Charles I, but this is not entirely the case. They became less popular, and were restricted largely to the foppish gentleman and would-be gentleman–a more restricted group of “gallants” than in the first half of the century.

“John Hardman the Famous Corncutter.” Hardman was a specialist in corns and bunions, and it is speculated, given the royal device hanging from his waistcoat, that he may have worked on King William III’s feet. Little is known about Hardman, and at least one early nineteenth century writer suggests he was Dutch given the English royal arms he is wearing (the author notes the large number of Dutchmen in London during the reign of William III), but possibly due in part as well to his mustache and earrings, and quite possibly because the author did not want to recognize an Englishman as a possible mountebank. Even so, it remains possible that Hardman was merely a flamboyant Englishman. Although the name’s roots are Germanic, it was and is a fairly common English surname. Note the long earring. British Museum.

References to earrings on men in the second half of the seventeenth century include a letter written by George Fox (of the Society of Friends, or Quakers) in 1654, but not published, I don’t believe, prior to the 1690s: “a company of them playing at bowls, or at tables, or at shuffle-board; or each taking his horse, that hath bunches of ribbons on his head, as the rider hath on his own (who, perhaps, hath a ring in his ear too)…” This isn’t too long after the execution of Charles I, when we might still see earrings (and which many secondary texts say is about the last time Englishmen wore earrings), and is at the beginning of the Golden Age of Piracy, assuming a start date of 1655 with the capture of Jamaica.

Henri de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt (1601-1666), known as “le Cadet la Perle” due to his bravery in battle. Earrings were quite common on military men in England, Scotland, and France in the first half of the seventeenth century, and on artists and others as well: a 1650 self-portrait of Rembrandt shows him wearing a pearl earring and a self-portrait of Ferdinand Bol shows him wearing a small gold hoop. Print by Nicolas de Larmessin, 1663. British Museum.

Goldsmith Louis Roupert, 1668. Print by Louis Cossin based on a painting by Pierre Rabon. Rijksmuseum.

Similarly, note the illustration below. Published in 1653 as part of an appendix satirizing the English gallant and his ostentatious dress and body ornamentation, it does prove that even at this date some English gallants still wore not only one, but two earrings at times. The author, Dr. John Bulwer, compares earring-wearing and other ostentation to that of foreign savages and heathens, or even to pre-Christian Britons, and appears to approve only of plain sober dress, as one might expect during the Age of Cromwell–up with the cropped Roundheads, down with the long-haired Royalists! “Children of vanity” is Bulwer’s disparaging, if also accurate on occasion, term for those who excessively ornament themselves. He also mocks gallants for wearing patches, starched collars (yellowed in fact with starch), flowing locks, mustaches, and so on. He is no less sparing of women. Curiously, Dr. Bulwer’s portrait shows him with flowing locks, a mustache, and goatee.

Illustration from “An Appendix of the Pedigree of the English Gallant” in Anthropometamorphosis: Man Transform’d: Or, the Artificiall Changling by John Bulwer. London: William Hunt, 1653. Dr. Bulwer’s work Anthropometamorphosis, in which he details the great variety of body ornamentation worldwide, is extraordinarily detailed for the era, sophisticated even by modern standards, even if more than a little bit patronizing. Dr. Bulwer is perhaps best known for proposing a system of sign language for the deaf.

Moving on to William Wycherly and The Plain-Dealer (one of my favorite plays), with a reference to the jewel in the ear and gunpowder spot on the hand, circa 1673, in the middle of the age of buccaneers. Originally I had considered the possibility that this might refer to the sea captain and not the fop, but other instances (George Fox above, for example), plus a re-reading, plus the opinion of a professor emeritus of seventeenth century English literature, have persuaded me that fops wore earrings more often than we think (the professor thought so, by the way)—enough to be an obvious reference for the audience. We’ll deal with gunpowder spots in another blog soon.

Head now to The Works of Mr. Thomas Brown: Amusements Serious and Comical, a comical and satirical group of works published in 1700, and we have the following: “I had honestly, deserved a better Reward than a Patch-box, a Toothpicker, and a small Ear-ring amounted to, and therefore need not disquiet my self upon that Score.. Thus you fee, Madam…” The gentleman has received several useful implements (but not what he was seeking) from his inamorata: an ear picker to clean his ears, a patch box for patches (fops wore them), and a single earring. The last might be simply a love token, but to what end if it can’t be displayed–worn, that is?

That French fops wore them is uncontested. By way of a nautical example, in 1704 the comte de Forbin, a famous, and arguably quite pompous at times, commerce-raiding French naval captain refused passage to a French monk who had been authorized travel from Livorno, Italy to France aboard the French warship by Cardinal de Janson. The monk wore a single gold earring with a large pearl, and Forbin specifically notes his foppish airs, that is, that he acted like a “petit-maître“–a fop or dandy. There were at the time a fair number of priests and monks as addicted to trappings of the flesh as to world beyond, if not more. In any case, it didn’t help that the monk was “haughty and arrogant.” In fact, it was probably this behavior that set Forbin off. But the captain’s reply to the monk was that the cardinal’s order said nothing about giving passage to a monk wearing an earring and giving the airs of a fop–so get off my ship.

In sum, if you want to be a sea rover with an earring but don’t want to be Dutch you might considering being a bit of a fop. This isn’t so very far-fetched, for their are examples of pirates wearing jewelry in a fashion that might be considered foppish. Quoting from The Golden Age of Piracy: The Truth Behind Pirate Myths, an overly fashionable pirate “might wear a ‘necklace of pearls of extraordinary size and inestimable price, with rubies of surpassing beauty’ as Captain Nicolas Van Horn did, or a gold chain with a ‘gold toothpicker hanging at it’ as Captain John James did (and many of his crew also wore gold chains), or a ‘gold chain round his neck, with a diamond cross hanging to it’ as Captain Bartholomew Roberts reportedly did.” (Citations to the quotations above can be found in the endnotes to The Golden Age of Piracy. The quotation is from the prologue.)

Even so, I do tend to agree a bit more with reenactors who object to this exception out of concern for the wrong impression. That said, I still would not be surprised to find a foppish pirate wearing an earring. Devotees of the early eighteenth century Anglo-American pirates will argue quite factually that most were seamen. This doesn’t alter the fact that there may have some foppish seamen–I’ve known some modern ones who’d fit this description, although they’re in the minority–and there were a few non-seamen as well who might fit the fop bill, including the dilettante pirate Stede Bonnet. In my experience, both in studying seamen of the past as well as having known and worked with many modern seamen–naval, commercial, tall ship–during my life, mariners as a group are not homogeneous even though they may express attributes common to their profession. In other words, they too have personalities and often express them through their clothing, hair, and other body ornamentation.

Detail from a late sixteenth century watercolor of a Timucuan casique of Florida, by John White. Note the large “earring” or ear piercing. Such ornamentation was common among Native Americans. British Museum.

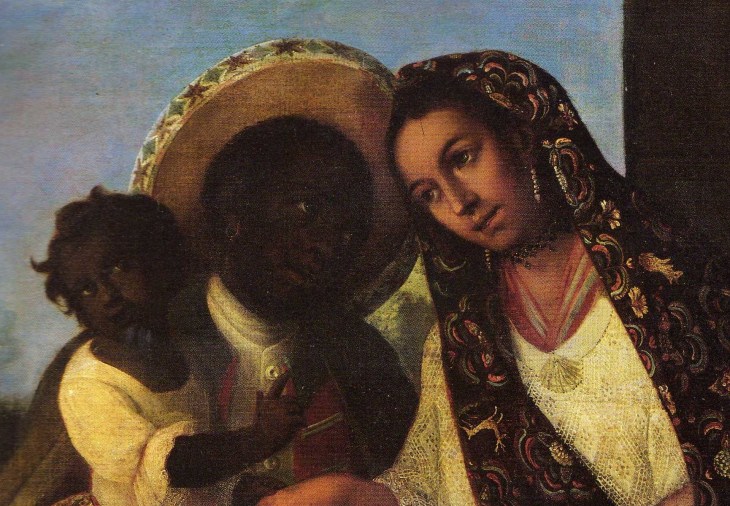

The third exception is that of Native Americans, Africans, and mixed races. This should be an obvious exception, but the fact that it is so often overlooked strongly suggests an ethnocentric–that is, a “white-centric” or “Euro-centric”–bias in the view of piracy and of the maritime in general. A fair number of English, French, and Dutch pirates and privateers, although not the majority, were non-white. The majority of Spanish pirates and privateers originating in the Caribbean were non-white. Many of these seafarers of color, particularly those of full African and Native American blood, probably wore earrings in one form or another.

Painting by Mexican artist Miguel Cabrera, circa mid-eighteenth century. The man is wearing an earring. The wearing of earrings among blacks and many men of mixed races was also common in the seventeenth century as well.

An African with a sword, quite possibly a West African slave trader. Seventeenth century. Sotheby’s.

Dutch school, a Moor, possibly a West African slave trader, smoking a churchwarden pipe. Seventeenth century. Christie’s.

Many period descriptions and images of Native American males mention or show earrings. Africans, and those of African descent, in European and American context in the seventeenth century are often shown wearing earrings, typically a single one. A large number of seventeenth century Dutch paintings show black servants and slaves wearing earrings, as does a painting of black Moor in North Africa and as does one of a possible West Indian slave trader.

One final note:

Earrings were a fashion statement!

Seamen of this era, including sea rovers, did not wear them to improve eyesight, pay for a funeral, or for any other nonsensical reason, no matter how reasonable such myths may seem when un-examined or otherwise taken at face value. Unfortunately, in spite of the wealth of accurate information readily available on the Internet, it has paradoxically fostered, or perhaps enhanced is more accurate, an intellectual laziness and willingness to believe anything in print.

Dear Cornwell, “From the old fort Blood surveyed Don Miguel’s squadron…,” oil on canvas, 1930, for the magazine serial edition of Captain Blood Returns. Mort Künstler Collection.

So, digressing slightly in order to speak historically about a fictional character, would Capt. Peter Blood actually have worn a large pearl earring as Rafael Sabatini described he did in Captain Blood Returns (aka The Chronicles of Captain Blood in the UK)? Of course he would have, for he meets two criteria: he has had service in the Dutch navy under de Ruyter and is, almost, a fop in his style of dress!

Copyright Benerson Little 2017. First posted July 2017. Last updated July 9, 2019.

[…] “[O]r was it the Gunpowder spot on his hand, or the Jewel in his ear, that purchas’d your heart?” sneers the manly Captain Manley (act. 2, sc. 1) to his former inamorata in regard to an obnoxious fop (they’re all obnoxious, aren’t they?) seeking her hand. At first glance it seems that Manley might be sarcastically referring to the lack of a gunpowder spot on the fop’s hand, and therefore that such spots were indicative of the seaman and therefore of the adventurer. Captain Manley, after all, was a fighting seaman. (Regarding the “Jewel in his ear” see Pirates & Earrings.) […]

LikeLike

[…] https://benersonlittle.blog/2017/07/05/pirates-earrings/ […]

LikeLike