Home » Posts tagged 'buccaneers'

Tag Archives: buccaneers

Captain Blood, Not Jack Sparrow: The Real Origin of Disney’s Wicked Wench Pirate Ship

It’s an epic image, one that anyone who’s ever cruised through the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction at one of the Disney theme parks is familiar with: a pirate ship cannonading — “firing its guns at” or “engaging” in sea parlance — a Spanish fort.

But the image-in-motion long predates the Disney attraction. In fact, as I’ll demonstrate shortly, the entire scene was lifted directly from Rafael Sabatini’s famous novel, Captain Blood: His Odyssey and especially from the 1935 film version starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Basil Rathbone. And the Wicked Wench pirate ship of the attraction was more than simply inspired by the Cinco Llagas / Arabella, as the ship in the novel and film was named: it was copied from it!

Originally the attraction depicted buccaneers in the second half of the 17th century attacking and sacking a Spanish town on the Main. “IN THE CROSS FIRE of cannonades between pirate ship and Caribbean port,” begins the caption of the 1968 Disney publicity still of the Wicked Wench shown above. It continues with “this crew of Disneyland adventurers sail through Pirates of the Caribbean as grape shot and cannonballs land around them. The pirate captain on his bridge gives the signal for an eight gun salute. The scene of one of ten action-packed segments in the thoroughly realistic re-creation of buccaneer days.” For now I’ll pass on correcting Disney’s descriptive language, as some readers might misconstrue such revisions as nautical pedantry.

However, in spite of the obvious historical basis for the ride’s inspiration, according to Disney’s modern Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise “canon” the Wicked Wench was instead the ship that would become the Black Pearl commanded by Jack Sparrow et al, more or less, post-buccaneer era. Not a buccaneer ship, in other words, but a later ship turned to pirate ship as would fly the Jolly Roger. This, of course, is nothing more than mere revisionism for the sake of marketing the ride on the coattails of the film series, and any “canon” (as in nearly all franchises) is nothing more than the result of a series of screenwriters trying to write popular scripts, and fans subsequently trying to make rabid sense of their details and many loose ends.

Myself, I much prefer the original orientation of the attraction, liberties taken with real buccaneer history notwithstanding. That said, comic ride though it may be (and one that I thoroughly enjoy), it does get some things right, including torture, pillage, and burning, not to mention the original implication of some scenes now altered from their original. We have, in fact, two versions of piracy in our culture: factual history and popular myth, the latter often overwhelming the former.

And now for the evidence that the Wicked Wench is really the Cinco Llagas / Arabella!

The Scene of Ship Attacking Fort Was Inspired by & Lifted Largely From the 1935 Film

One need only to watch the 1935 Captain Blood to confirm this. The only difference between the two is that the roles are reversed: rather than a Spanish pirate attacking the principal town of an English colony in the late 17th century as in the Rafael Sabatini novel and the film based on it, buccaneers in the attraction attack a Spanish town, as they often successfully did — and far, far more often than Spanish pirates did against English, French, and Dutch colonies.

In fact, in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Black Pearl there is an homage to the pirate attack in the 1935 film version of Captain Blood: some of the shots of locals running for cover are quite similar to those in Captain Blood.

For more details on the ship-versus-Spanish fort trope, see “The Iconic “Spanish” Fort: Only a Spanish Galleon Says “Pirates” Better!“

The battle depicted in the Disney ride, and by derivation the one in Captain Blood, was given an homage in The Curse of Monkey Island (LucasArts, 1997).

The Wicked Wench is Red Like the Cinco Llagas / Arabella of the Novel

According to Rafael Sabatini, who clearly emphasized the sanguinary nature of buccaneering via the hero’s name and other thematic elements, the color of Peter Blood’s pirate ship was red. However, red was not an exceptionally common color of ships at the time. Red paint was typically used for the bulwarks (the inner “walls”), gun carriages, and often some fittings of men-of-war, and some other ships as well, at the time, and the upper works (the upper outside of the hull) and sterns of some ships were occasionally painted red — but never the entire hull. However, the application of pine tar, tallow, and linseed oil could lend a reddish hue to hull planking (particularly to those ships built of various “mahoganies” in the Americas), but this would not cause a ship to be referred to as red. (Far more details on the possible appearance of the Cinco Llagas / Arabella are forthcoming in Treasure Light Press’s annotated Captain Blood.)

And the Wicked Wench? A red ship, of course!

The Profiles of the Wicked Wench and the Cinco Llagas / Arabella are Too Similar to be Coincidental

Indeed! The similarity is obvious when comparing the images below. Even the scrollwork on the stern upper works is almost identical (see the image above and also at the end of this section). Disney did make some alterations to suit the attraction, including reducing the ship from two decks to one, and, of course, making it small enough to fit in the attraction.

And Then There’s the Names of the Ships…

After its capture by a handful of renegade rebels-convict led by Dr. Peter Blood, the Cinco Llagas was renamed the Arabella after the woman Blood loved but thought he could never have. Arabella Bishop, although independent, strong-willed, and anything but swooning (or languishingly voluptuous!), was still a lady in manners and mores, unlikely to (sadly!) run away to sea in men’s clothes with Peter Blood. One can easily see a tongue-in-cheek homage to Arabella and the Arabella in the renaming of the Spanish frigate as the Wicked Wench, and even in the “Woman in Red” in the old Bride Auction scene on the attraction.

Likewise the captain of the Wicked Wench as an inverted homage: no clean-shaven gentleman buccaneer he, unlike Captain Peter Blood, but bearded and beribboned like Blackbeard the Pirate and bellowing in G-rated curses like Robert Newton or Peter Ustinov in their piratical film roles. That is, before Hector Barbossa took his place to align with the film franchise. (N.B. Blackbeard was not a buccaneer but a later black flag pirate, and although most buccaneers appeared to have been clean-shaven, some French boucaniers, and therefore buccaneers, did wear beards.)

For more details on “The Woman in Red,” now “Redd the Pirate,” (and in any case, an anthropomorphism of the ship by both), see “The Women in Red: The Evolution of a Pirate Trope.” For more details on the black flag — the so-called Rackham flag with skull and crossed cutlasses — flown by the Wicked Wench, see “The Fanciful, Mythical “Calico Jack Rackham” Pirate Flag.” Note that on the Disney LP featuring a narrated soundtrack of the ride, the Wicked Wench is referred to as the Black Mariah, the name of the ship in “Donald Finds Pirate Gold!” Perhaps Wicked Wench was suitable on the stern but not in narration at the time on an LP likely to be listened to mostly by children?

So, Was the Wicked Wench Really the Arabella?

Only Disney knows — and only Disney can answer how the Arabella, sunk among the cays just off Port Royal, Jamaica in 1689 while defending the town from French attack, came to be raised, refitted, and ended up again in buccaneer, then pirate, hands… 🙂

And the Black Pearl?

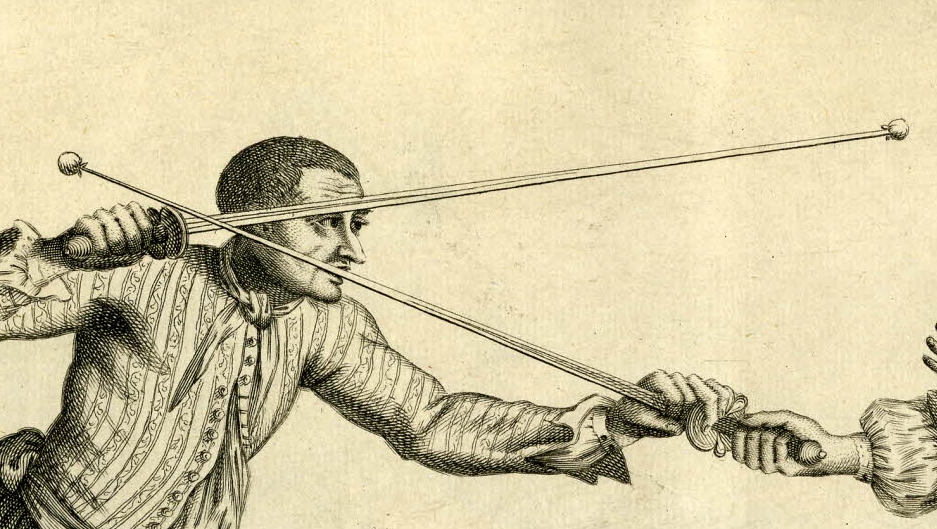

If you’re looking for the real original inspiration for the Black Pearl, discard any notion of it having been the Wicked Wench — this is probably just “canon after the fact.” Convenient revisionism for the sake of marketing, in other words. Sparrow’s famous ship is more likely inspired ultimately by Tom Leach’s 40-gun Black Swan, from Sabatini’s novel of the same title. Or at the very least it corresponds closely to Sabatini’s description of the ship, including its black hull. Even the un-authorized plastic model of Sparrow’s Black Pearl is sold under the name of the Black Swan. Are there similarities between the Wicked Wench and the Black Pearl? Of course there are. Clearly the set designers took a look at the Wicked Wench, but it is much closer to the Arabella. (By the way, the duel in The Black Swan is described here.)

And for you budding “nautical pedants” out there, here’s the correction to the Disney text quoted above: “this crew of Disneyland adventurers [an acceptable term: French buccaneers aka flibustiers were often referred to as adventurers] sail through Pirates of the Caribbean as grape shot [this form of small shot was in its early development and generally not known by this name at this time] and cannonballs [more correctly, round shot] land [splash] around them. The pirate captain on his bridge [quarterdeck, not bridge] gives the signal for an eight gun salute [a correct humorous euphemism for a broadside]. The scene of one of ten action-packed segments in the thoroughly [and humorous] realistic re-creation of buccaneer days [a statement more correct than it might appear at first]…”

Post Script: The Wicked Wench is Not the Only Disney Pirate Ship Inspired By an Errol Flynn Film…

Disney’s Jolly Roger, from the animated version of Peter Pan (1953), bears a striking resemblance to the Albatross from The Sea Hawk (1940, directed by Michael Curtiz and starring Errol Flynn). 🙂

Copyright Benerson Little 2022-2024. First posted June 22, 2022. Last updated February 9, 2024.

Holiday Greetings!

With the floor beneath the tree still looking like the decks of the Arabella just before she sank in her final swashbuckling action, here are a few lines in sweet memory of past Christmas mornings and in happy anticipation of future ones, at least for anyone who has ever pretended to be the pirates of fiction and film–or who inspires such fantasy in their children:

“Bars of gold and pieces of eight,

Spanish galleons of goodly freight;

Buried treasure to seek and gain:

Lads [and Lasses]! what ho, for the Spanish Main!”

–A. E. Bosner, The Buccaneers: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Pirates & Puritans

In recognition of the Thanksgiving Holiday, a few words from fictional and factual accounts about Puritans and their rather unsurprising early support of pirates and most especially–most because, in other words–their plunder.

I’m well aware, as are most readers, that Thanksgiving’s origin lies with Pilgrims and Native Americans, and the Pilgrims were not Puritans, at least not as we generally think of them. Historians tell us the Pilgrims were Brownist Puritans, a separate sect. Even so, there’s a strong association with Puritans and the holiday, correct or not, doubtless due to the dominance of the “purifying” faith soon after in seventeenth century New England (i.e. purifying the Church of England of so-called Catholic practices). And some historians do date our modern Thanksgiving to a Puritan celebration of Thanksgiving in 1631. I’ll leave the hair-splitting to the specialists in this area.

In Fiction

Fiction offers surprisingly few accounts good of Puritans and pirates, at least relative to other peoples and places, and pirates. Of those that exist, the most famous is surely the brief but fact-based description in Nathanial Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter :

“Not to speak of the clergyman’s health, so inadequate to sustain the hardships of a forest life, his native gifts, his culture, and his entire development, would secure him a home only in the midst of civilization and refinement; the higher the state, the more delicately adapted to it the man. In furtherance of this choice, it so happened that a ship lay in the harbor; one of those questionable cruisers, frequent at that day, which, without being absolutely outlaws of the deep, yet roamed over its surface with a remarkable irresponsibility of character. This vessel had recently arrived from the Spanish Main, and, within three days’ time, would sail for Bristol. Hester Prynne—whose vocation, as a self-enlisted Sister of Charity, had brought her acquainted with the captain and crew—could take upon herself to secure the passage of two individuals and a child, with all the secrecy which circumstances rendered more than desirable…

“They Were Rough Looking Desperadoes.” Illustration by Hugh Thomson for The Scarlet Letter (New York: George H. Doran, 1915).

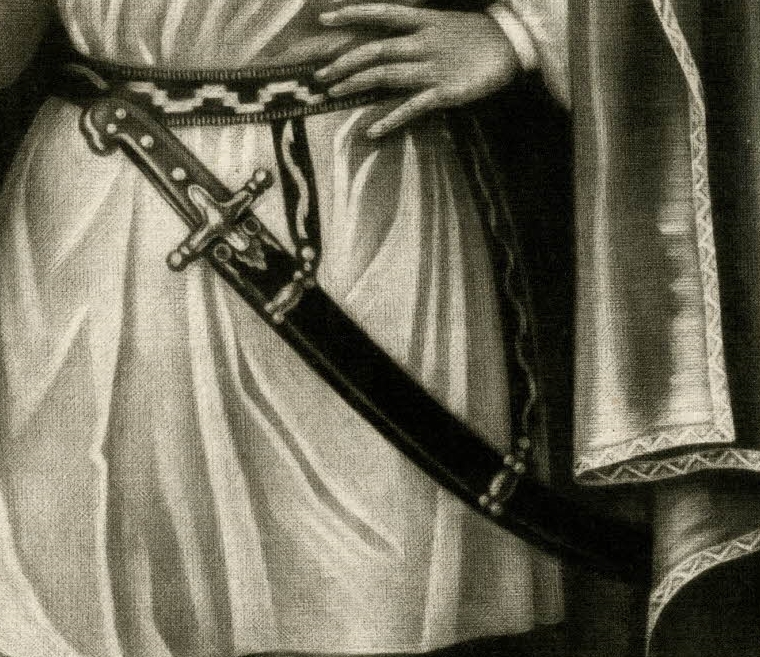

“The picture of human life in the market-place, though its general tint was the sad gray, brown, or black of the English emigrants, was yet enlivened by some diversity of hue. A party of Indians—in their savage finery of curiously embroidered deer-skin robes, wampum-belts, red and yellow ochre, and feathers, and armed with the bow and arrow and stone-headed spear—stood apart, with countenances of inflexible gravity, beyond what even the Puritan aspect could attain. Nor, wild as were these painted barbarians, were they the wildest feature of the scene. This distinction could more justly be claimed by some mariners,—a part of the crew of the vessel from the Spanish Main,—who had come ashore to see the humors of Election Day. They were rough-looking desperadoes, with sun-blackened faces, and an immensity of beard; their wide, short trousers were confined about the waist by belts, often clasped with a rough plate of gold, and sustaining always a long knife, and, in some instances, a sword. From beneath their broad-brimmed hats of palm-leaf gleamed eyes which, even in good-nature and merriment, had a kind of animal ferocity. They transgressed, without fear or scruple, the rules of behavior that were binding on all others; smoking tobacco under the beadle’s very nose, although each whiff would have cost a townsman a shilling; and quaffing, at their pleasure, draughts of wine or aqua-vitæ from pocket-flasks, which they freely tendered to the gaping crowd around them. It remarkably characterized the incomplete morality of the age, rigid as we call it, that a license was allowed the seafaring class, not merely for their freaks on shore, but for far more desperate deeds on their proper element. The sailor of that day would go near to be arraigned as a pirate in our own. There could be little doubt, for instance, that this very ship’s crew, though no unfavorable specimens of the nautical brotherhood, had been guilty, as we should phrase it, of depredations on the Spanish commerce, such as would have perilled all their necks in a modern court of justice.

“But the sea, in those old times, heaved, swelled, and foamed, very much at its own will, or subject only to the tempestuous wind, with hardly any attempts at regulation by human law. The buccaneer on the wave might relinquish his calling, and become at once, if he chose, a man of probity and piety on land; nor, even in the full career of his reckless life, was he regarded as a personage with whom it was disreputable to traffic, or casually associate. Thus, the Puritan elders, in their black cloaks, starched bands, and steeple-crowned hats, smiled not unbenignantly at the clamor and rude deportment of these jolly seafaring men; and it excited neither surprise nor animadversion, when so reputable a citizen as old Roger Chillingworth, the physician, was seen to enter the market-place, in close and familiar talk with the commander of the questionable vessel.

“The latter was by far the most showy and gallant figure, so far as apparel went, anywhere to be seen among the multitude. He wore a profusion of ribbons on his garment, and gold-lace on his hat, which was also encircled by a gold chain, and surmounted with a feather. There was a sword at his side, and a sword-cut on his forehead, which, by the arrangement of his hair, he seemed anxious rather to display than hide. A landsman could hardly have worn this garb and shown this face, and worn and shown them both with such a galliard air, without undergoing stern question before a magistrate, and probably incurring fine or imprisonment, or perhaps an exhibition in the stocks. As regarded the shipmaster, however, all was looked upon as pertaining to the character, as to a fish his glistening scales.”

Hawthorne’s description is quite factual. Owing to the need to write this piece as efficiently as possible (I’m either busy or lazy, or both), I’ll quote here, and later several times, from The Buccaneer’s Realm (Potomac Books, 2007), or at least from the draft, this being easier than consulting the print version for which I have no digital copy, the book being edited on paper–old school, that is.

“Sailors [in New England] are almost certainly exempt anyway from much of this [religious] authority of the petty sort, or at least visiting pirates and privateers are, provided they keep to the “ordinaries and publique houses enterteinment” [James Duncan Phillips, Salem in the Seventeenth Century, 1933] on the waterfront where they commonly spend large sums drinking. There probably never has been, nor is there likely to ever be, a busy seapor t that lacks the taverns and women that [historically male] sailors seek when ashore, no matter the local moral culture. Mariners are tolerated in such places because they are a necessity–even tavern keepers may be precluded from arresting sailors for non-payment of their drinking debts, in order that ships can sail with their full crews. Nor can a sailor’s maritime character be much altered anyway, at sea or ashore. New England, after all, is not only a Puritan culture but a quintessentially maritime one, with a history of privateering, a major shipbuilding industry, seven hundred thirty or more vessels ranging from six to two hundred fifty tons in 1676, and a great trade to the English colonies,Europe, and even Guinea, Madagascar, and “Scanderoon” (İskenderun, also called Alexandretta). It is impossible to imagine a Puritan selectman attempting to enforce a law against kissing in public, for example, against a filibuster or buccaneer whose hands are figuratively speaking still red with blood and whose plunder is aiding in the financial salvation of the colony.

Buccaneers & Puritans

Again, an excerpt from The Buccaneers Realm:

In August 1678, privateer Bernard Lemoyne, fitted out in France, armed with a commission from Governor Pouançay at Saint Domingue, commanding the Toison d’Or (Golden Fleece) and in consort with Captain Pérou and perhaps others as well, cruises the south Cuban coast. In Matanzas Bay these privateers capture three Dutch trading ships ranging from twenty-four to twenty-six guns, and a Spaniard of twenty guns. Sailing to Martinique, the seat of French government in the Caribbean, to have the prizes condemned, Lemoyne faces a strident objection from the majority of his crew. Being English(although recruited at Petit Goave), they prefer to carry the prizes into an English port. However, by sailing with the French they have obviously refused Governor Vaughan’s offer of amnesty at Jamaica, as well as violated the law against serving under a foreign commission, and so these English must carry their prizes elsewhere, and so they do, to Boston, where they and their French captain are received with open arms. The reception is not surprising: the total value of the prizes, including one lost on the coast but whose cargo of any significant value is saved, is estimated at three hundred thousand pieces-of-eight.

That various sea rovers find their way to New England should come as no surprise: the New World is full of them. That some Puritan merchants support piracy should come as no surprise, either: Puritans have been involved in piracy and privateering since the 1630s when they briefly colonized Providence (Santa Catalina) and Henrietta (San Andrés) in the Caribbean as bases from which to raid England’s great hated rival, Catholic Spain.[ii]Further, New England has just endured King Philip’s War, a bloody conflict that has left the economy in shambles and the Faithful wondering what this manner of“God’s Providence” portends. The sudden influx of goods and silver is needed and surely welcomed, and any rationale is better than none. After all, the prizes were seized under a French commission and condemned in Martinique. Bostonians are merely providing a reasonable market.

New Englanders will continue such support throughout the period, with even less scruple, permitting the “refitting at the dock at Boston” in 1684 of the Spanish prize La Paz (Peace), renamed la Mutine and commanded by Captain Michel (Andrieszoon). She was captured near Cartagena by a French squadron commanded by Laurens, and whoseother captains included Michel, Yanky (Willems), Le Sage, Bréha (Bart), Blot, Grogniet,and an unidentified Englishman. With her is the Françoise, originally captured by the Spanish from the French and called by her captors the Francesa, then re-captured by Laurens at the same time as La Paz, and which has now passed to Yanky’s command. The Spanish ship is rich with goods: “The Bostoners no sooner heard of her [the Paz] off the coast than they despatched a messenger and pilot to convoy her into port in defiance of the King’s proclamation.” The filibusters purchase much of the “choice goods” in Boston,and thus “are likely to leave the greatest part of their plate behind them.” (CSPC 1681-1685, nos. 1845, 1851.)

In 1683 Captain Henley fits out a ship in Boston and sails for the Red Sea, seeking the Mogul’s rich ships. Associated with him are the pirate captains Thomas Woolery and Christopher Goff, and in 1685 both Henley and Goff are proclaimed pirates. The pirates Graham and Veale briefly visit in1685, but are recognized as pirates who have attacked an English vessel. In the same year the pirate Jean Hamlin returns to the sea in a ship named after his first and notorious vessel: “The new Trompeuse was fitted and protected by the godly New England independents.” Woolery returns to Boston in 1687 from “the South Sea,” after burning his ship at New Providence. New England is confirmed as a pirate “retreat.” (CSPC 1681-1685, nos. 2042, 1563; CSP 1685-1688,nos. 207, 210, 1405, 1449, 1449i, 1555.)

Puritans have a distinct reputation in both religion and trade, perhaps best described by the caustic Ned Ward: “The Inhabitants seem very Religious, showing many outward and visible Signs of an inward and Spiritual Grace: But tho’ they wear in their Faces the Innocence of Doves,you will find them in their Dealings, as Subtile as Serpents. Interest is their Faith, Money their God, and Large Possessions the only Heaven they covet…And it is a Proverb with those that know them, Whosover believes a New-England Saint, shall be sure to be cheated: And he that knows how to deal with their Traders, may Deal with the Devil and fear no Craft.” (Edward Ward, A Trip to New England, 1699.) Scholar Philip Ainsworth Means writes that for the Puritans, money was “to be worked for enthusiastically, all to the Glory of God,” and that, indeed, Puritans are “the establishers of [the United States’] present attitude toward business affairs,” although certainly the Dutch of New York influence it as well. (Means, The Spanish Main, 1935.)

However, New England is neither a single colony nor completely homogeneous. Rhode Island has a similar reputation as Massachusetts,at least in regard to support of pirates, or privateers of dubious commission,based some say on Rhode Island’s permissive coastline. Here John Coxon threatens to bring his cargo of indigo stolen in 1679 at the Bay of Honduras,if he is not permitted to unlade the cargo at Jamaica, paying duties on it, of course–the pirates would be “well entertained” at Rhode Island. In 1683 two pirate vessels, one of them commanded by Thomas Paine, are also well-received at Rhode Island. Governor Cranfield of New Hampshire asks Rhode Island authorities to arrest them, but is rebuffed. New Hampshire and Connecticut are said to be clones of Massachusetts in government and religion, and which way the original Puritan colony goes, so they go, although the governors of New Hampshire do attempt to reign in the Assembly, a creature of the Puritan congregational ministers. The colony also gives aid and protection to Spanish prisoners who escape from a French pirate in Boston, for example, and Governor Cranfield informs the English government of Massachusetts’s pandering to pirates.

Puritan influence extends to some degree both to the Caribbean and to English buccaneers as well. Many of the early buccaneers are English soldiers recruited under Cromwell’s “Western Design” with its failed Cromwell attempt against the Spanish at Hispaniola,followed by the conquest of Jamaica, and certainly some of them are either Puritans,or were, or have absorbed the Puritan ethos prevalent in Cromwell’s army. The courageous and famous Captain Richard Sawkins, a “generous man” who throws dice overboard in anger when he finds buccaneers using them on a Sunday, is almost certainly an heir to some degree of this Puritan tradition. Robert Clarke, “Governor and Captain General of the Bahamas,” independent preacher, and granter of piratical commissions “to make war on the Spaniards of Cuba, St. Augustine, and others,” is one of Oliver Cromwell’s former officers, and likewise heir to the Lord Protector’s Puritan and military traditions, as are many in the Caribbean.[

New England not only receives various pirates and “privateers,” but even has those who settle here. One of them, Samuel Moseley of Dorchester, Massachusetts, commands the Salisbury ketch, a coast guard with crew of forty-seven, along the New England coastlinefrom 1673 to 1674 in order to defend against Dutch incursions. Moseley is admirably suited to the job, for he reputedly has been a buccaneer or“privateer” at Jamaica. In 1675 he is commissioned to seek Dutch “pirates” who have been attacking English traders along the coast of Acadia. Sailing in consort with a French vessel, he soon discovers the trio of Peter Roderigo commanding the Edward and Thomas, Cornelius Andreson commanding the hired boat Penobscot Shallop, and George Manning, an Englishman captured by the Dutch and who has taken up their cause, commanding the Phillip Shallop. However, the issue is not as simple as it seems.

Roderigo and Andreson are actually legitimate privateers. Roderigo, a “Flanderkin,” Andreson, a Dutchman, and JohnRhoades, an Englishman serving as pilot, were recently officers under HurriaenAernouts of the Dutch Flying Post-Horse privateer, attacking and driving off the Frenchalong the Acadian coast. Aernouts lawfully claimed Acadia for Holland, and before he departed for the Caribbean commissioned Roderigo, Andreson, and Rhoades to manage the trade along this territory of “New Holland.” Aernouts subsequently sails with Reyning in an attack on Granada, but both are captured by the French. Unfortunately for the officers he leaves behind, English traders interlope on the Dutch-claimed territory. The officers steal sheep from ashore,and order traders at sea to strike “A Mayne for the Prince of orainge,” then rob them of “Beaver and Moose” pelts and skins. (To “strike amain” is to lower topsails, or mainsails if topsails are not set, to indicate submission or surrender.[iii]At one point, Roderigo beats Edward Youring, one of his English crewmen who objects to the theft of English goods. He is left ashore for a day “to be starved with could [cold].”

In response, the English accuse them of piracy, and it is in this pretended capacity that Captain Moseley engages them. The battle is over quickly. The Dutch vessels are tiny, and Manning suddenly changes sidesand engages his Dutch consorts. Mosely bids the Dutch “A Mayne for the King of England,” and Youring lowers Roderigo’s mainsail three or four feet to indicate surrender, in spite of orders to the contrary. Now attacked three to two, and by vessels flying English, French, and Dutch colors, Aernouts’s officers strike for true. Roderigo is convicted of piracy, but pardoned. Andreson is found guilty after the judges direct the verdict, having been first acquitted. The eight remaining are soon tried. Three, including Rhoades, are to be banished.The five others are condemned, including John Williams who had once served under Captain Morris, the famous buccaneer who killed the famous pirate Manoel Pardal Rivera, a Portuguese in the service of Spain. In 1682 Williams will again be in trouble for piracy, this time in Hartford, Connecticut.[iv]

The story does not end here. King Philip’s War breaks out, and Captain Moseley soon leads a company of volunteers, old soldiers, prisoners, and others against the Wampanoag leader [in this early example of unjust war against Native Americans]. The privateer earns a reputation for both courage and cruelty; his hatred of all Native Americans, friend or foe, is implacable. He is a butcher of men. In this company sometimes called “Moseley’s Privateers” are several condemned men condemned for piracy. Among these is Captain Andreson, who is soon commended for his bravery in the field in both Moseley’s and Wheeler’s companies, and pardoned. Captain Roderigo serves in Captain Scottow’s company, and similarly distinguishes himself and is likewise pardoned. King Philip’s War has everyone’s attention–none of the condemned are ever put to death.[

Pirates & Puritans

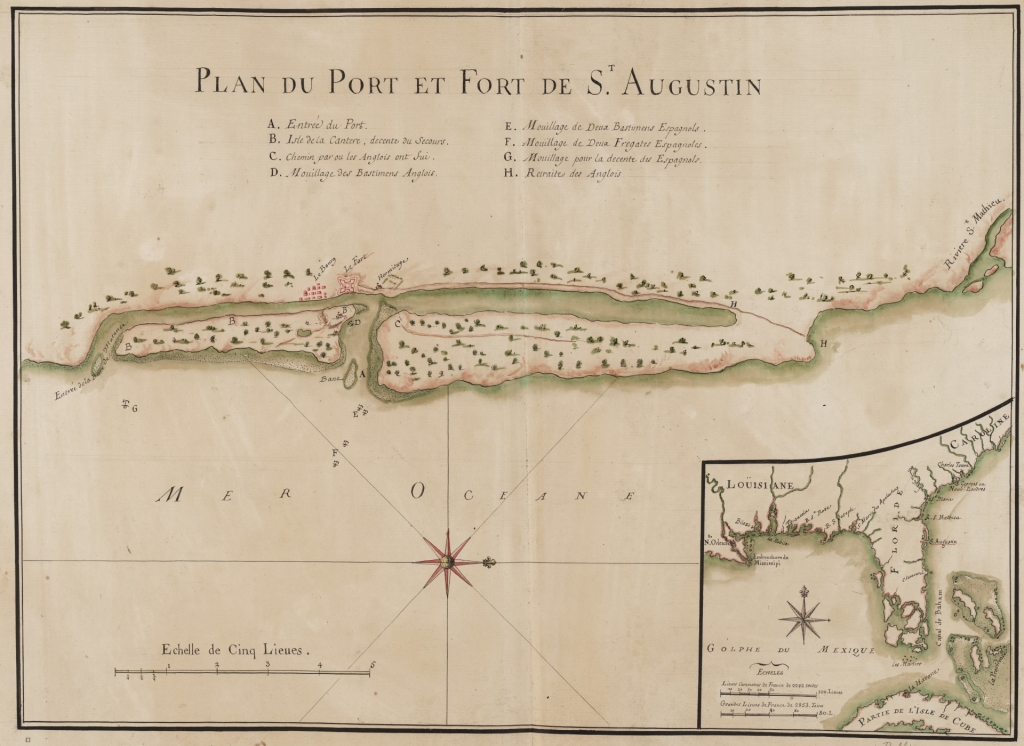

(Leventhal Map and Education Center.)

Moving into the early eighteenth century, a period of fascination for many–the time of Blackbeard, Roberts, and their ilk–, I won’t add much on them for now. Their Puritan and Massachusetts contacts were largely associated with piracies in local waters, and, quite deservedly, hangings for such crimes. I’m much less interested in these pirates, considering them little more than thugs with armed ships. Largely composed of privateers angry at losing their traditional trade in a depressed economy when peace arrived, they made no significant attacks by land, ran from most fights with naval vessels and others armed against them, lost nearly all fights with the English navy, and succeeded largely because there wasn’t an adequate local naval presence.

Their entire reputation in the Anglo-American community is based largely on the fact that they had great early publicity (Charles Johnson) which Hollywood adopted and expanded; talked bigger and badder than they really were; captured a large number of vessels (but mostly by frightening poor merchant crews into submission); and, frankly, because their make-up was largely Anglo-American (none of those French or other foreigners to share the credit with). As for their purported colorblindness toward people of darker skins: it didn’t really exist. They were inveterate slavers, just like honest seamen were. For reasons of cognitive dissonance I think (we like pirates but need to rationalize much of their behavior so we don’t feel bad about liking them), these pirates have been variously turned into social and political rebels, “knights of the sea,” and persecuted “good guys.” In fact, although there is always some small kernel of truth to all of these imaginings, it is not enough to change the simple fact that these men were armed thieves at sea, willing to use violence against innocent seamen and passengers.

I’ve dealt thoroughly with these issues in The Golden Age of Piracy.

For those interested, I highly recommend George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630-1730, 1923. It’s a fun read with plenty of excerpts from original accounts.

If I do have an interest in early eighteenth century piracy and Puritans, it’s with that grand old hypocrite and religious extremist, the Reverend Cotton Mather. An interesting and often despicable man, he celebrated the infamous witch trials, wrote an excellent but unpublished book on medical practice (including advice on getting fresh air and exercise, and not smoking), supported inoculation against smallpox in spite of strong opposition, and wrote and published books and pamphlets on a variety of subjects ranging from theology to history.

He also preached and published against pirates sentenced to hang in the early eighteenth century.

And hang them the devout New Englanders did.

Regarding citations, I have only used them in the case of quotations. Additional citations may be found in The Buccaneer’s Realm.

Copyright Benerson Little, 2007, 2018.

Evoking Swashbuckling Romance: Hollywood Pirate Ships & Shores in Miniature, & More

A brief place-holder blog post (and at the bottom a not quite shameless plug for Blood & Plunder by Firelock Games) while I finish several more challenging posts in the queue.

Before the advent of CGI, many swashbuckler films used models of ship and shore, along with full-size ships built on sound stages, to both recreate environments no longer available and also to save money. To some degree the early miniatures may seem quaint today, as compared to CGI, although in my opinion bad CGI is worse–more jarring to the eye–by far than an obvious model.

These old sets and scenes evoke nostalgia for the entire spectacle of old Hollywood swashbucklers: the cinemas with their great screens and clicking film projectors, the lasting impressions left by thundering broadsides and clashing swords, and above all the image of pirate ships in tropical waters.

For fun, here are a few.

Publicity still, The Sea Hawk (Warner Bros., 1940).

Above, the Albatross, commanded by Capt. Geoffrey Thorpe (Errol Flynn) arrives in a secluded cove on the Isthmus of Panama in order to raid the silver trains. The film scenes set in the Old World are in black and white, while those in the Americas are in sepia.

Only the film title is actually based on the novel by Rafael Sabatini, which tells the story of an English gentleman who turns Barbary corsair in an act of revenge. The 1940 film is a not even thinly-veiled wartime propaganda piece, albeit an enjoyable one. English sea dogs are renamed in the scrip as patriotic sea hawks suppressed by treasonous machinations until the doughty hero (Errol Flynn) reveals the treachery and England arms the sea hawks against Nazi Germany Imperial Spain. For more information try The Sea Hawk, edited by Rudy Behlmer. It’s a fun read for anyone interested in the script and the film’s history.

Publicity still, Captain Blood, Warner Bros., 1935.

Next, we have the models of Port Royal and the French flagship used in the finale. This image is not of an actual scene from the 1935 Captain Blood starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Basil Rathbone, but of the set prior to shooting.

Detail from the photograph above.

Of course, the real Port Royal looked nothing like this. It was actually crammed with English-style brick buildings of two and even three floors, unlike this Southern California Spanish colonial revival-influenced town. But it’s sets like these in Hollywood swashbucklers that have influenced our notions of what the seventeenth century Caribbean looked like. In fact, the region at the time had a wide variety or environments and architectures.

Publicity still, Captain Blood (Warner Bros., 1935).

Above we have the battle in Port Royal harbor during the finale of Captain Blood: the Arabella on the left versus the French flagship on the right. N. B. Royal sails (the smallest on the ship on the right, the fourth sail from the bottom) were not used in this era. Their use here is an anachronism. In fact, only exceedingly rarely was the topgallant sail (the third sail from the bottom, used on “tall ships” on the fore and main masts) seen on the mizzenmast or sprit-mast on the bowsprit. I know of only two seventeenth century instances, each noted as being highly unusual. One was Kidd’s Adventure Galley in the very late seventeenth century, the other was a Spanish ship in 1673.

Publicity still, The Black Swan (Twentieth Century Fox, 1942).

A pirate ship under full sail in action against ships at anchor and shore targets during the finale of The Black Swan starring Tyrone Power and Maureen O’Hara. The film is based on the somewhat similar novel by Rafael Sabatini.

Screen capture, The Spanish Main (RKO 1945).

A pirate ship sailing into Cartagena de Indias under the guns of a castle in The Spanish Main starring Maureen O’Hara and Paul Henreid.

Publicity still, Against All Flags (Universal International Pictures, 1952).

Over-large pirate ship and treasure ship of the “Great Mogul” in Against All Flags. The ships are engaged under full sail, a practice generally not seen in reality except in the case of a running fight, but quite common in Hollywood because it looks good. Here, both ships would have stripped to “fighting sail” for a variety of reasons, including simplified ship-handling in action. The film stars Errol Flynn, as Brian Hawke, in one of his last swashbucklers (followed finally by The Master of Ballantrae in 1953 and Crossed Swords in 1954). It also stars Maureen O’Hara wielding a sword as Prudence ‘Spitfire’ Stevens, something I always enjoy.

Image courtesy of Firelock Games.

And now, a not quite shameless plug for Firelock Games’s Blood & Plunder tabletop war game of piracy and much, much more–one need not take the side of pirates to play. A full spectrum of peoples and forces are available.

Full disclosure: I’m the game’s historical consultant, and I thought it would be fun to compare the Blood & Plunder models to the film models above.

So, above and coming soon: a small Spanish galleon. Historically accurate, the model also evokes the best of old Hollywood swashbucklers.

Image courtesy of Firelock Games.

A small Spanish frigate engaged with a French brigantine.

Image courtesy of Firelock Games.

Spanish and French brigantines engaged near shore. Which is the pirate? (Answer: either could be!)

Photo courtesy of Firelock Games.

A small fluyt (in English a pink, in French a flibot, in Spanish an urqueta, on the left; a galleon at center; a brigantine on the right.

Photo courtesy of Firelock Games.

Close up action!

Image courtesy of Firelock Games.

Brigantine crewed by, I believe, French flibustiers.

Information about the game is available on Facebook and the company’s website.

Copyright Benerson Little 2018. First posted April 16, 2018.

Jack Sparrow, Perhaps? The Origin of an Early “Hollywood” Pirate, Plus the Authentic Image of a Real Buccaneer

The small caption reads “Cover Drawn and Engraved on Wood by Howard McCormick.” Author’s collection.

The illustration above was created in late 1926 or early 1927, and published in April of the latter year. Among its several pirate clichés (skull and bones on the hat, tattoos, curved dagger, long threatening mustache) is one I had thought was entirely modern: a pirate hair braid with coins attached.

Quite possibly, this coin braid is the artist’s idea of a pirate “love lock.” The love lock was popular among some young English and French gentlemen in the first half of the seventeenth century. Usually worn on the left side, it was typically tied with a ribbon, a “silken twist” as one author called it. Occasionally two were worn, one on each side as in the image below.

Henri de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt (1601-1666), known as “le Cadet la Perle” due to his bravery in battle. He is also sporting a pair of love locks. Print by Nicolas de Larmessin, 1663. British Museum.

This “pirate love lock” is a noteworthy characteristic of the very Hollywood, very fantasy pirate Captain Jack Sparrow, and I wonder if this image did not inspire much of his look. Historically-speaking, though, there is no historical basis for it among pirates of the “Golden Age” (circa 1655 to 1725), although it’s possible there may have been a gentleman rover or two who wore one during the first half of the seventeenth century–but not a braid or lock with coins.

Of course, much of The Mentor pirate image above was clearly inspired by famous illustrator and author Howard Pyle, as shown below.

Romantic, largely imagined painting of a buccaneer. From “The Fate of a Treasure-Town” in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December 1905. The image is reprinted in Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates.

“How the Buccaneers Kept Christmas,” Howard Pyle, Harper’s Weekly, December 16, 1899, a special two-page image. I’ve discussed this image in Of Buccaneer Christmas, Dog as Dinner, & Cigar Smoking Women.

A classic Howard Pyle line drawing, from Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates.

There’s a hint of N. C. Wyeth too, not surprising given that he was a student of Howard Pyle. However, Captain Peter Blood was a gentleman pirate, and the pirate on The Mentor cover is clearly not.

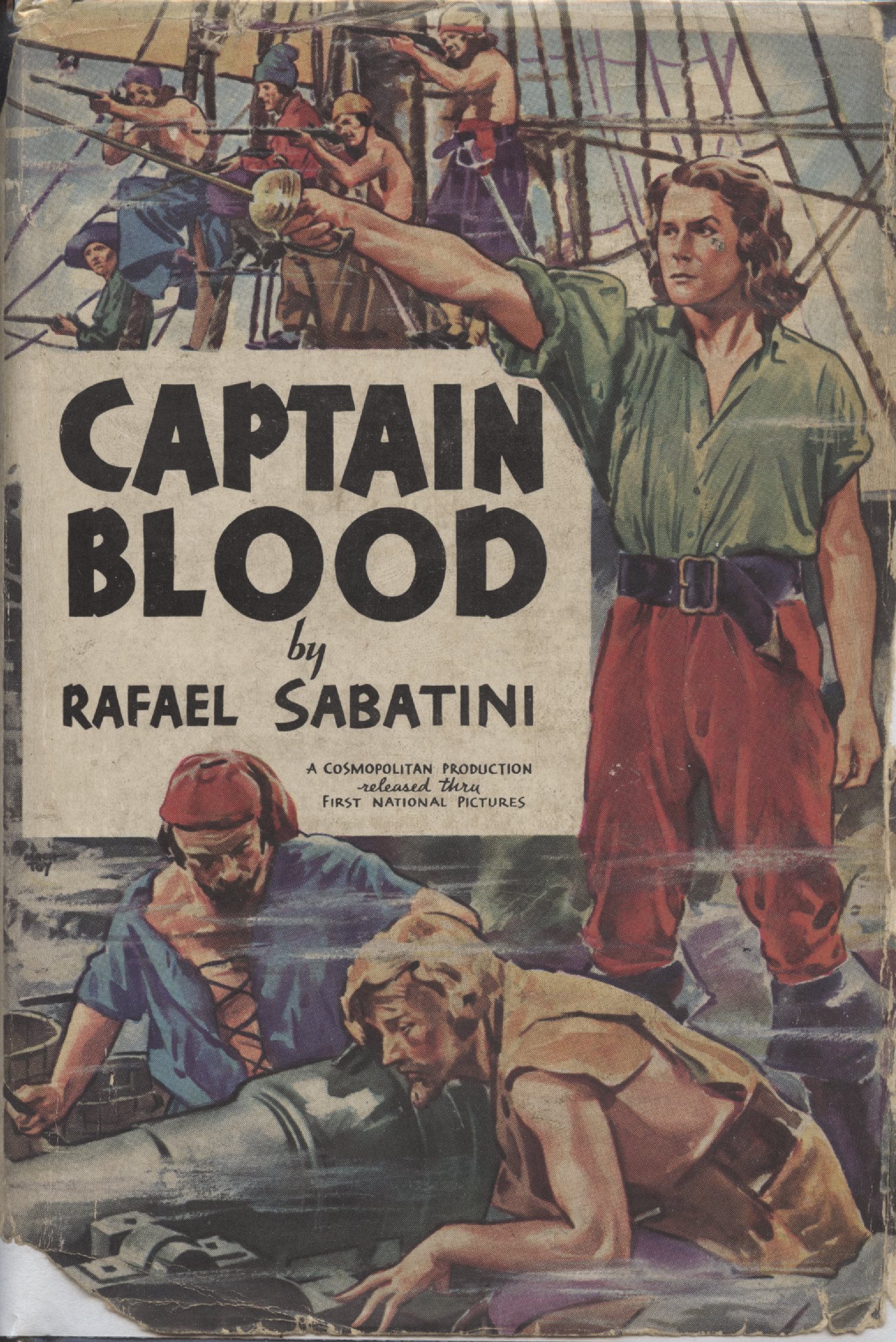

Battered dust jacket from the photoplay edition of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini, 1922. The cover art and identical frontispiece artwork by N. C. Wyeth.

And Wyeth’s Captain Blood cover is clearly influenced by this 1921 cover he painted for Life magazine. In fact, less the goatee, the two buccaneers might be one and the same:

Details about the painting can be found at the Brandywine River Museum of Art. Oddly, the Life magazine issue has no story or article about buccaneers or pirates.

“The Pirate” by N. C. Wyeth. Pretty much the same pirate as immediately above, less the fictional “pirate boots,” this time painted for Hal Haskell Sr., a Dupont executive who commissioned it in 1929. For years the painting hung in Haskel’s yacht, and afterward to the present in the family home. The print is available from The Busacca Gallery, Art-Cade Gallery, and other vendors.

The Pyle influence continued through the twentieth century in film, illustration, and mass market paperbacks about pirates…

“Pirate Dreaming of Home” by Norman Rockwell, 1924. The painting is also clearly based on Howard Pyle’s famous painting, “The Buccaneer Was a Picturesque Fellow,” and may be intended to represent the same buccaneer later in life, or perhaps is simply an homage to Pyle. (Norman Rockwell Museum.)

The Mentor illustration is also clearly influenced by Douglas Fairbanks’s 1926 film The Black Pirate, which was, according to Fairbanks himself, heavily influenced by Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates and to a fair degree by Peter Pan.

Seriously, check out Fairbanks’s costume in the film, it’s obviously that of Peter Pan grown up. I have a soft spot for Douglas Fairbanks: my first fencing master, Dr. Francis Zold, described him as a gentleman and a swordsman, and described how Fairbanks invited the Hungarian fencers to his mansion Picfair (named after Fairbanks and his wife, Mary Pickford) after György Jekelfalussy-Piller won the gold saber medal at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games.

Anders Randolf as the pirate captain in The Black Pirate. Note the skull and bones on the hat, the dagger in the mouth, the hoop earring, and, just visible, the tattoo on the chest. Screen capture from the Kino Blu-ray. A useful review of the film is available here.

Publicity still, possibly a frame enlargement from B&W footage given the grain, of the admirable duel on the beach between Randalf and Fairbanks, choreographed by Fred Cavens. More on this in a later blog post. Author’s collection.

And here, finally, we have Johnny Depp as Jack Sparrow in the flesh, braids and such dangling from his hair, again for which there is no historical precedent among Golden Age pirates that we know of. It’s hard to see how Depp’s costume, in particular his hair, might not have been influenced by the illustration at the top of the page. If it weren’t, it’s quite a coincidence.

“Captain Jack Sparrow makes port” from the Jack Sparrow Gallery on the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean website.

Jack Sparrow again, with a closer look at his braids &c. from the Jack Sparrow Gallery on the Disney Pirates of the Caribbean website.

As noted, it’s entirely possible that the Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl costume designers never saw the image at the top of the page. They may have imagined it themselves, or been influenced by something else. A very likely possibility is Donald O’Connor in the 1951 film Double Crossbones, a campy pirate comedy that makes fun of nearly all pirate clichés.

Donald O’Connor in Double Crossbones. Note the braid over his right ear. (Screen capture.)

Although this may seem to be little more than coincidence, there are other similarities between the two films, strongly suggesting the writers and costume designers were familiar with it. In particular, O’Connor plays a shy, somewhat bumbling shopkeeper’s apprentice in love with the governor’s beautiful ward, and she with him. Due to difference in social class he’s unwilling to express his love openly until by accident he becomes a pirate. Sound familiar? Even the costumes of the governor’s ward (Lady Sylvia Copeland, played by Helena Carter) are similar (homage-fashion?) to those of Elizabeth Swann, played by Keira Knightley. If not the Pirates of the Caribbean costume designer, then perhaps the Double Crossbones costume designer was familiar with the image at the top of the page.

Screen captures from Double Crossbones, 1951. Plenty of candlesticks, not to mention a painted miniature around the neck instead of a magical Aztec coin.

And there’s another film possibility: Torin Thatcher (a pirate’s name if ever there were!) as Humble Bellows in The Crimson Pirate (1952). Bellows wears a love knot, perhaps to compensate for his balding pate. It’s surely better than a comb-over! Disney may have been inspired by Bellows’s coiffure, for, like Double Crossbones above, there are numerous homages, shall we say, to the film in the Disney franchise, ranging from the way soldiers march to the “walking boat underwater” scene. It’s also possible that Donald O’Connor’s ‘do inspired Bellows’s.

Torin Thatcher as Humble Bellows in The Crimson Pirate (1952). Blu-ray screen capture.

Of course, all this so far is “Hollywood,” for lack of a better term. There are a number of serious groups of reenactors, scholars, and others trying to correct the false historical image, all with varying degrees of accuracy, agreement and disagreement, and success.

Hollywood has yet to get aboard, no matter whether in pirate films and television series, or often any film or television set prior to the nineteenth century for that matter, probably because it’s easier to play to audience expectations (and, unfortunately, much of the audience doesn’t really care), not to mention that there’s a tendency or even a fad among costume designers to do something that “evokes” the image or era rather than depict it accurately, not to mention the time and other expense of researching, designing, and creating costumes from scratch when there are costumes “close enough,” so to speak, already in film wardrobes.

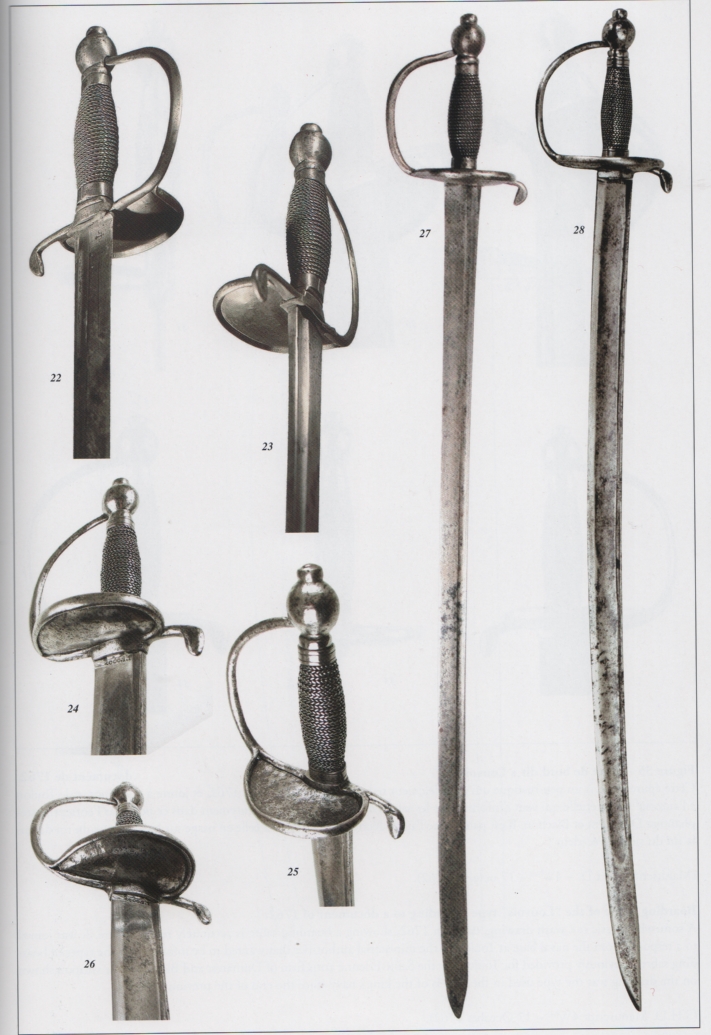

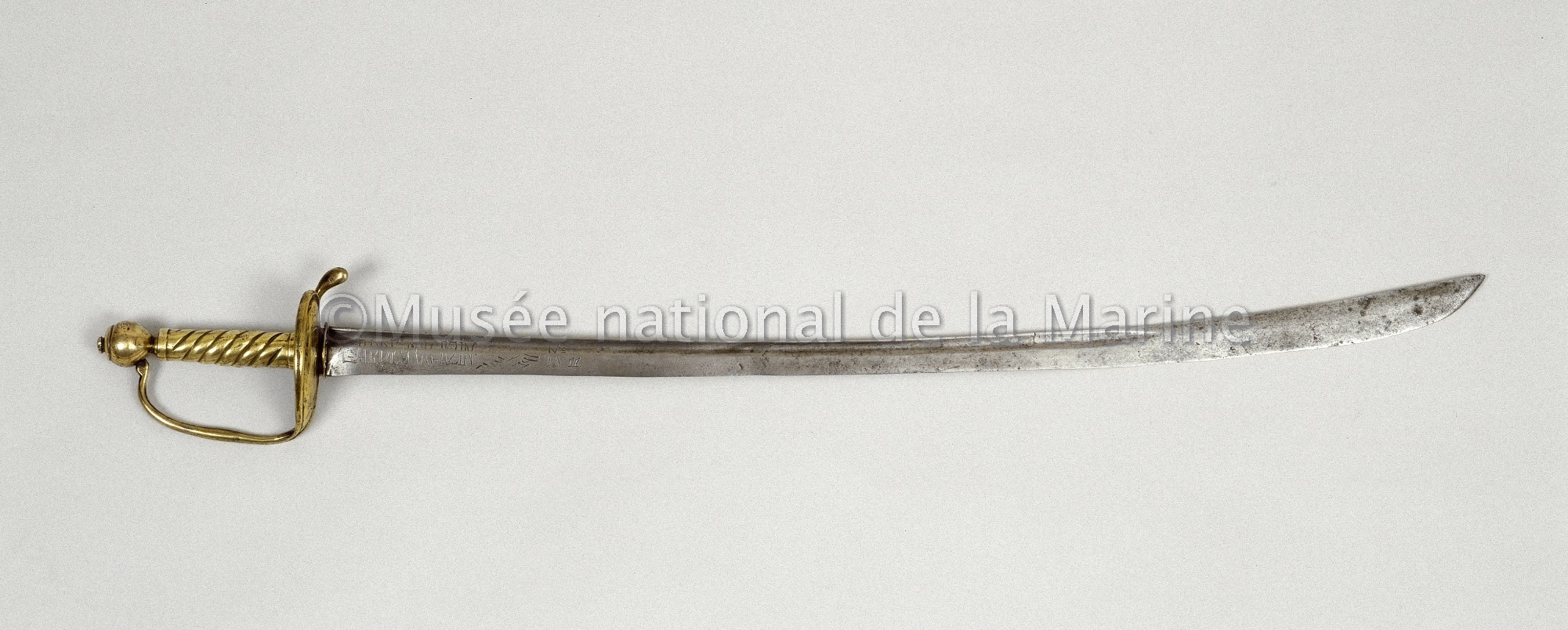

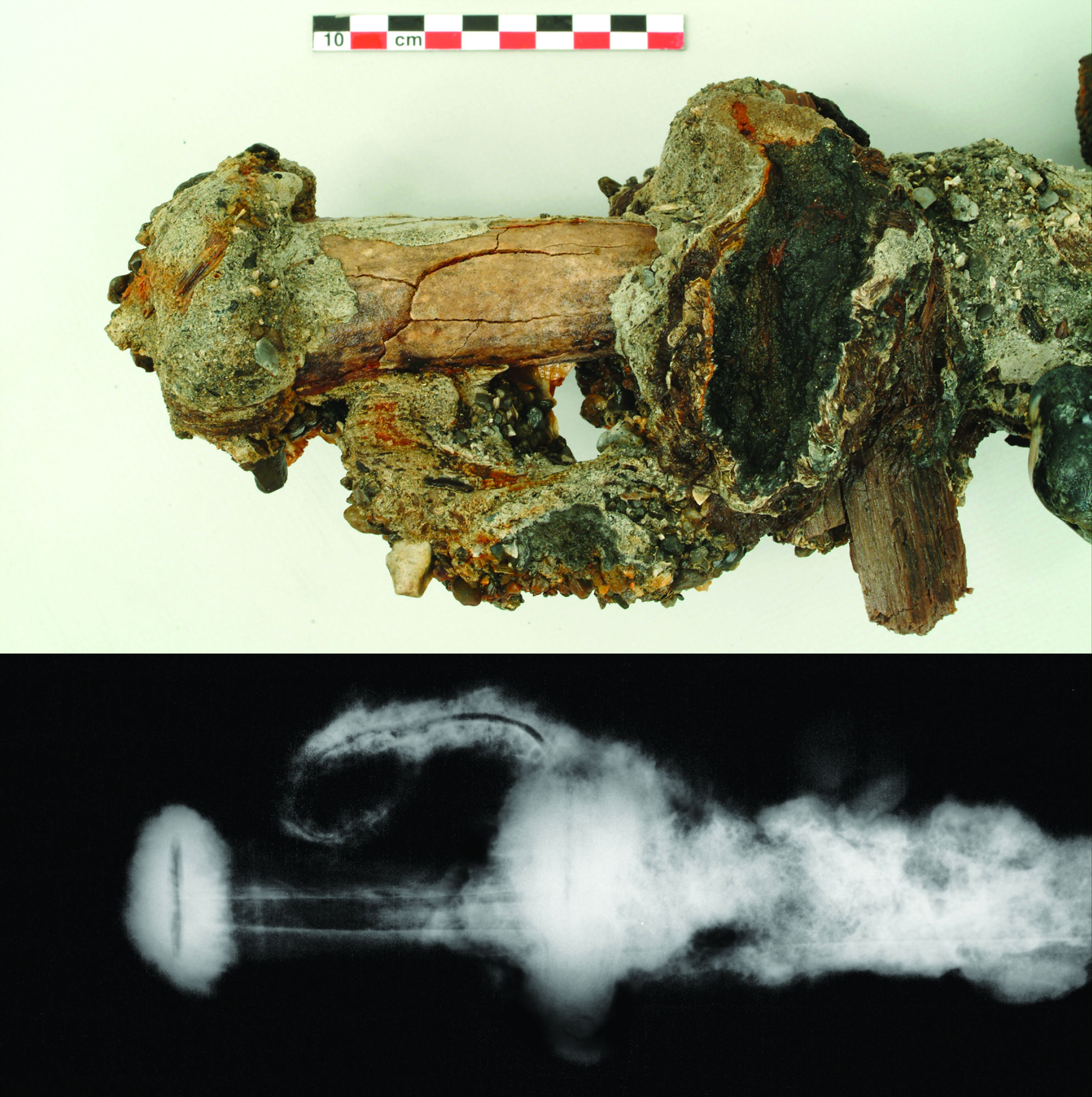

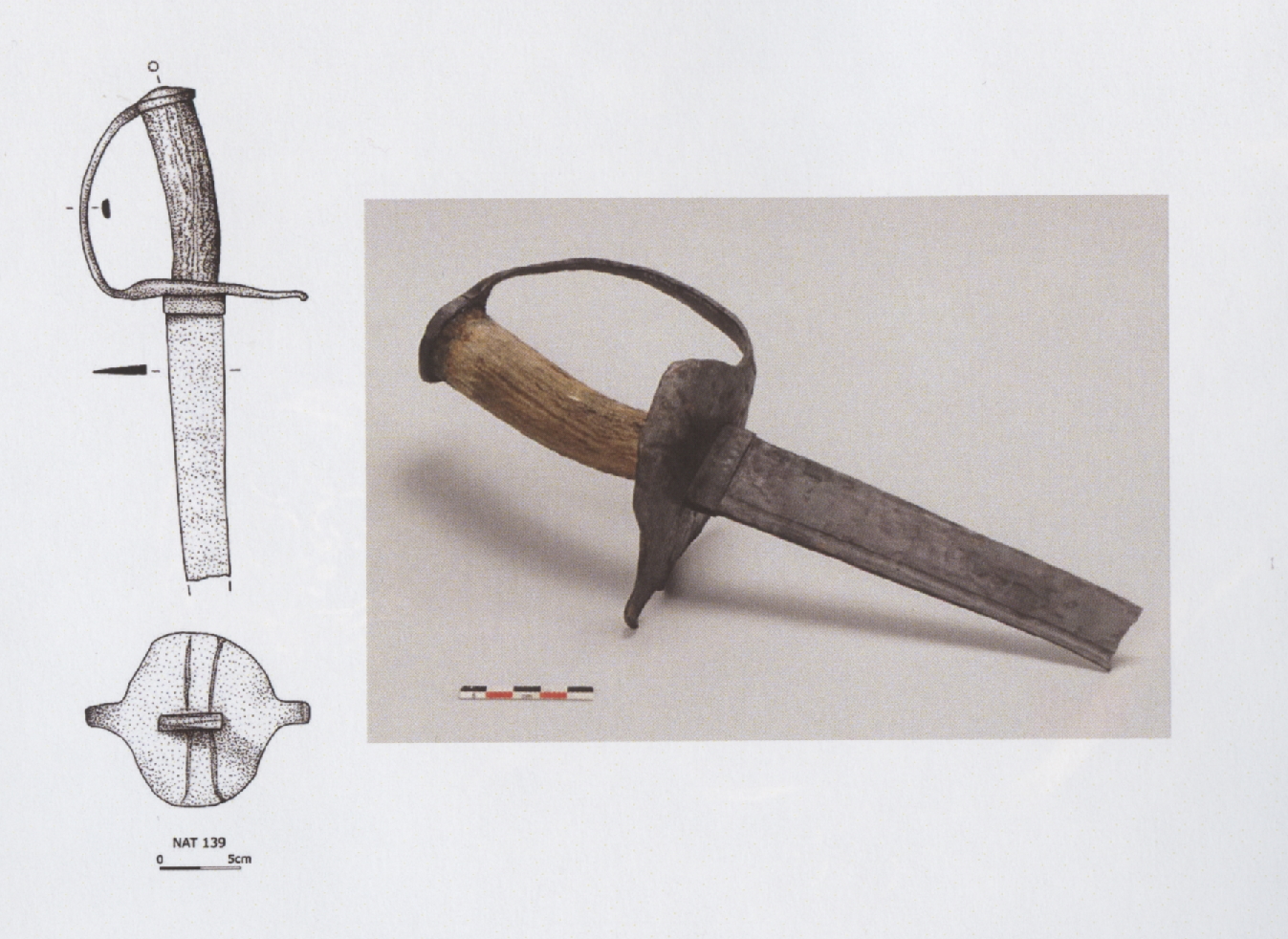

Here’s a hint, Hollywood: you can start by getting rid of the “pirate boots.” They didn’t exist. They’re actually based on riding boots, and a pirate would only be in riding boots if he were on a horse–and horses aren’t often ridden aboard ship. Further, you can get rid of the baldrics in most cases, exceptions being primarily for gentlemen pirates wearing smallswords into the 1680s, no later. (You can have some Spanish pirates with rapiers wear baldrics after this, though.) And for that matter, you can get rid of wide belts and large belt buckles too. But if nothing else, please, please get rid of the boots, which, if I recall correctly, a UK journalist once correctly described as nothing more than fetish-wear.

Full disclosure: I was the historical consultant to Black Sails, a great show with a great cast and crew, but I had nothing to do with the costuming, much of which is considered as near-blasphemy by advocates of historical accuracy in material culture in television and film. That said, the show is a fictional prequel to a work of fiction that variously created or expanded some of our biggest myths about pirates–buried treasure, the black spot, and so on. Looked at this way, if you can accept the story you can probably tolerate the costuming.

I’ve discussed what real pirates and buccaneers looked like several times, not without some occasional minor quibbling by other authorities. The Golden Age of Piracy has some details, as do two or three of my other books, but several of my blog posts also discuss some of the more egregious clichés, with more posts on the subject to come.

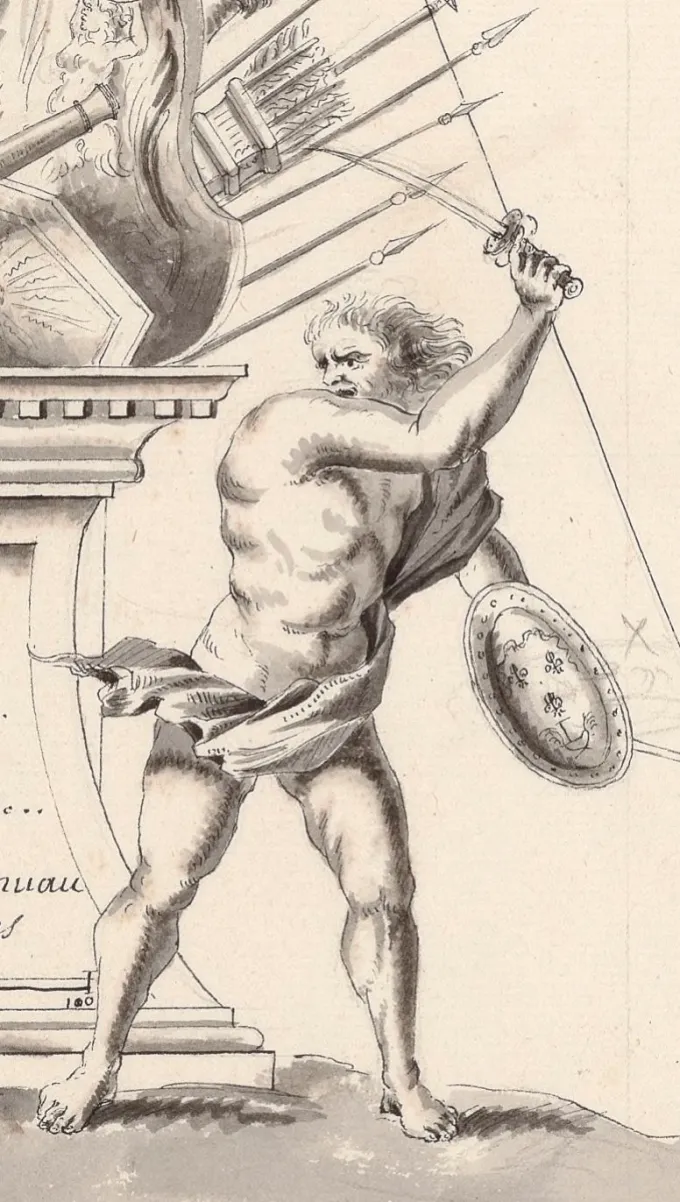

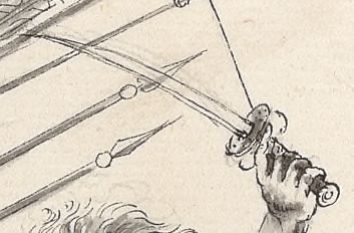

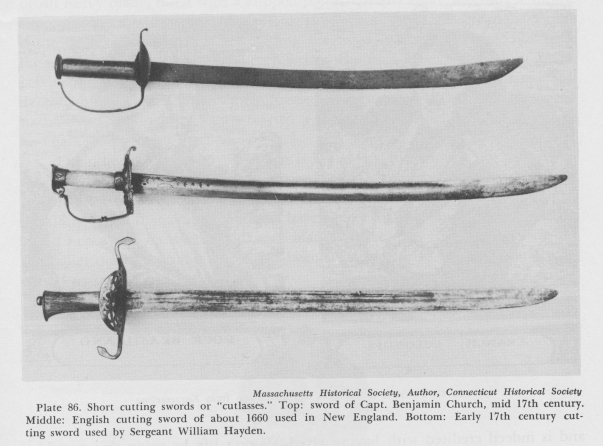

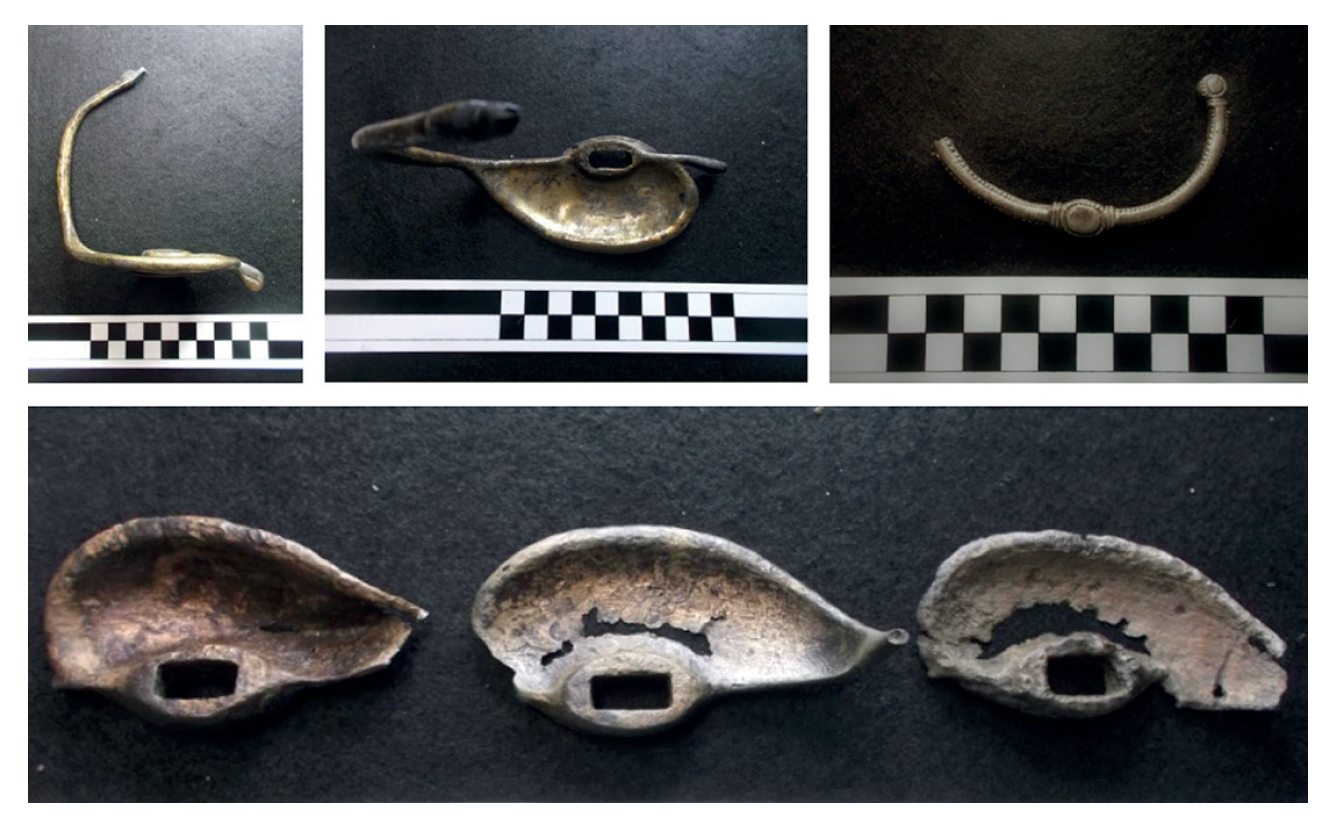

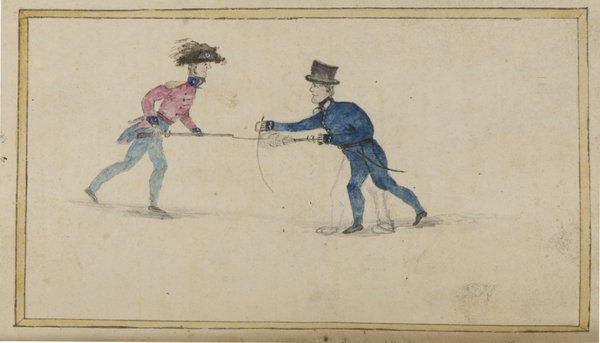

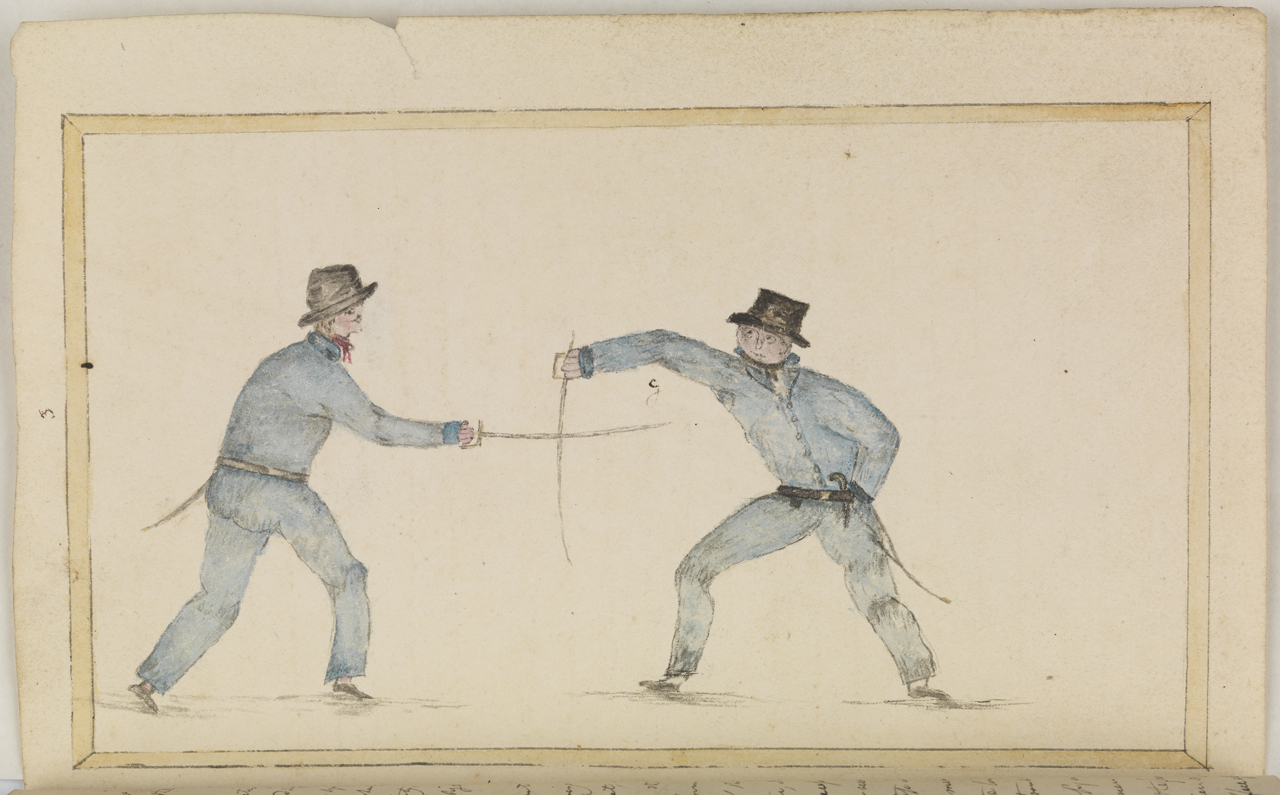

At any rate, here’s an image of a real buccaneer, a French flibustier in fact, from the 1680s. It’s an eyewitness image, one of only a handful of authentic eyewitness images of “Golden Age” sea rovers. It and the others prove that an image may evoke swashbuckling pirates while still being entirely accurate.

One of several eyewitness images of French flibustiers (buccaneers) in the 1680s. These are the only known eyewitness images of Golden Age sea rovers. They went largely unnoticed and without commentary until I ran across them by accident while researching late 17th century charts of French Caribbean ports. I’ve discussed them in an article for the Mariner’s Mirror, and also in these two posts: The Authentic Image of the Real Buccaneers of Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini and The Authentic Image of the Boucanier. The posts include citations to the original images.

Copyright Benerson Little 2018. First published January 23, 2018. Last updated April 4, 2018.

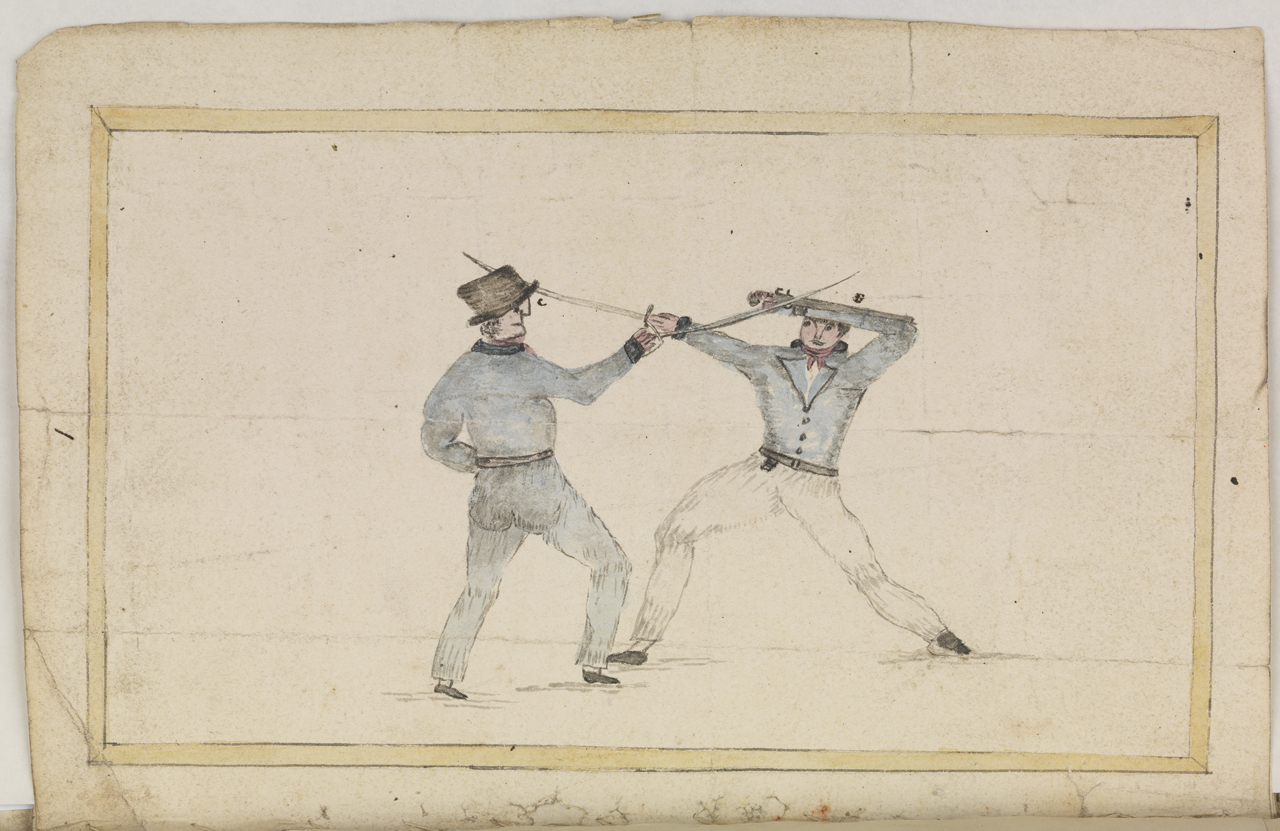

Pirate Versus Privateer

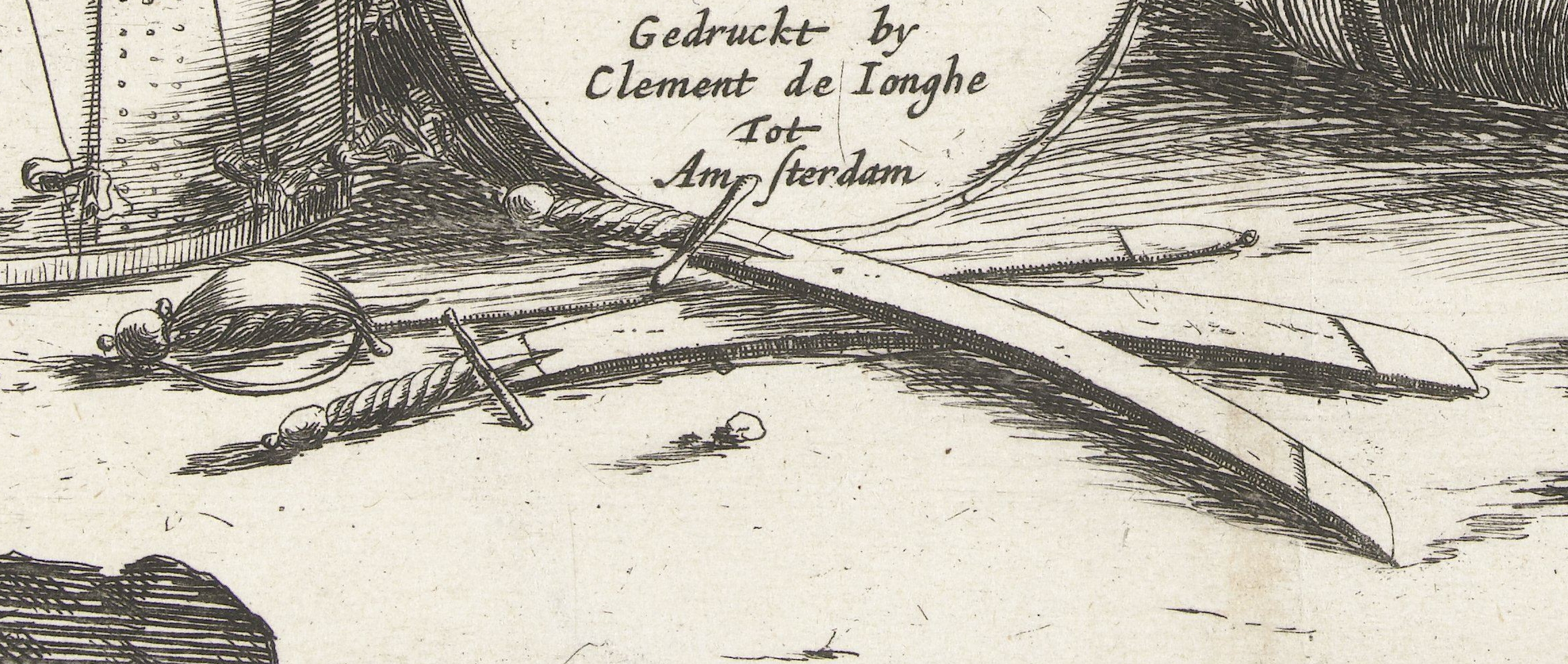

English privateer sloop engaging a Spanish merchantman during the War of Jenkins’ Ear. Detail from a chart of New Providence, 1751. Library of Congress.

A few quick notes on the use of the word pirate when the term privateer is appropriate.

It’s a minor issue, I know, this particular instance of the practice known today as “click-bait.” The practice has been around a long time, not only in political rhetoric but in marketing as well. But it has grown much worse over the past decade, and, given the state of affairs today in regard to the truth, in which outright lies often pass with too little outcry, and, almost as bad, in which mere unfounded opinion is often given equal time with solid expertise, any egregious usurpation of fact or meaning should be shunned–even in such a trivial-seeming matter of pirate versus privateer.

I am not entirely innocent of the charge myself, but in my defense it’s not been an egregious offense, and one generally committed by my publishers primarily because the word pirate is so marketable, not to mention that publishers invariably retain the right to change or even outright reject the author’s title.

For example, The Sea Rover’s Practice: Pirate Tactics and Techniques is actually about the tactics of pirates, privateers, and commerce-raiding men-of-war. But pirate is the word used in the subtitle, a decision made by my publisher. Likewise The Buccaneer’s Realm: Pirate Life on the Spanish Main 1674-1688: buccaneers were often pirates, but also often legitimate privateers as well as what might best be termed “quasi-privateers” or “quasi-pirates” operating without a legitimate commission but with a “wink and a nod” from their respective governments. Pirate Hunting: The Fight Against Pirates, Privateers, and Sea Raiders From Antiquity to the Present also discusses privateers, commerce raiders, and even early submarines. The Golden Age of Piracy is the most accurate, but, as noted already, even buccaneers were often privateers.

English privateer sloop with Spanish prize in tow during the War of Jenkins’ Ear. Detail from a chart of New Providence, 1751. Library of Congress.

Strictly speaking, piracy is armed robbery on the open seas. In the past, it was armed robbery pretty much anywhere there was ocean or land touching the ocean, at least if the thieves came by sea. Not just a crime, but a hanging crime, in other words.

Privateering, however, derives from private man-of-war, a vessel commissioned by a legitimate state to attack enemy shipping and profit from it. Lawful plundering, in other words, an entirely legal practice. A privateer might be imprisoned by the enemy if captured, but he wouldn’t be tried and hanged for piracy.

I’ve made plain in print many times that there is plenty of overlap among the various sorts of sea rover, that is, among pirates, privateers, and commerce-raiding men-of-war. That said, in most cases during the Golden Age of Piracy (circa 1655 to 1725) and afterward, the overlapping is much less common. In particular, the distinction is readily apparent everywhere except in the case of Caribbean buccaneers during the Golden Age (and strictly speaking, the only period in which true buccaneers existed).

In other words, in the majority of cases the distinction between pirate and privateer is obvious. Privateers in no ways considered themselves to be pirates, nor did anyone else except in a figurative sense by some of their their victims. Only if a privateer had overstepped his lawful authority and entered the realm of piracy might he be considered a pirate. Privateers did not claim to be pirates. Rather, they rejected the term outright. You’d get into a fight if you called a privateer a pirate, quite possibly a fatal one in the form of a duel.

“An English Indiaman Attacked by Three Spanish Privateers.” Willem van de Velde the Younger, painting dated 1677. Strictly speaking, the privateers were Ostenders commissioned by Spain. Royal Collection Trust.

So how does the use of the word pirate in the title of my books, and in similar books, differ from books and articles in which pirate is used as a term for privateer? Because my books and others like them are largely about piracy. Were they largely about privateering, the word privateering, not piracy, would appear in the titles.

Pirate and piracy have become romantic words, so it’s easy to see why they’re used whenever possible, however tenuous the connection to the subject. They’re therefore commonly used as umbrella terms for anything resembling plundering at sea, lawful or not. And they’re used in spite of the reality of piracy being anything but romantic to the usually entirely innocent victims: common seamen, coastal inhabitants, free people of color taken and sold as slaves by pirates, not to mention slaves captured by pirates and sold elsewhere, often away from their families.

In fact, it should be privateering and pirate hunting that convey the most romance, with piracy conveying revulsion, as it did in the past.

But it’s the caricature that matters: the word pirate conveys the image that draws the eye, and the description the ear.

“An English Ship in Action with Barbary Vessels” by Willem van de Velde, 1678. National Maritime Museum. The Barbary vessels were privateers, commonly known as Barbary corsairs. They were not pirates, notwithstanding that the term was sometimes, and often still is, applied. They were actually legitimately commissioned privateers. The reason they are often referred to as pirates is because (1) they were not Christians, and (2) they captured and enslaved white Europeans. The irony that white Europeans enslaved black Africans (and other people of color as well) seems to have been lost. (Note: This painting was used for the Pirate Hunting dust jacket.)

Part of the problem with the lure of the word is that piracy has been re-interpreted as a form of rebellion against injustice. Pirates, we are told by too many scholars both amateur and professional, were rebels against empire, against unfair corporate practices, even–falsely–rebels against slavery. They are mostly the “good guys.” We are told that they may even have helped inspire the American Revolution and that they even threatened the existence of the English and other empires. Although there are occasional fragments of related truth in these claims, none of them are profoundly true or even slightly more than less true. They are not even as true as the suggestion that privateers were a form of pirates.

The fact is, we’re attracted to pirates so we sanitize them, we invent reasons, and let others invent reasons, why they weren’t as bad as they were. We make them palatable.

But to reemphasize, pirates were sea criminals, and in no way did their victims view them as heroes. Simply reading through a list of pirate cruelties and other depredations should be enough to correct the false image–but seldom does it. Privateers, although some did break the law at times, were by comparison Boy Scouts.

There are periods in history in which some groups of commissioned privateers behaved piratically: Spanish Caribbean privateers in the Golden Age, French and English buccaneers in the Golden Age, Colombian privateers during the South American wars of revolution (and likewise Spanish men-of-war fighting Colombian privateers), for example. But they are in the minority as compared to the enormous number of commissioned privateers, and when privateers did commit piratical acts, they were considered to be pirates. However, the majority of privateers behaved lawfully or largely lawfully, restricting their attacks to enemy shipping as permitted by law. The majority of privateers should never be referred to as pirates, nor should the term pirate be a catch-all for any sea rover, legitimate or other.

A View of ye Jason Privateer by Nicholas Pocock, circa 1760. Bristol City Museums. Downloaded from British Tars 1740 -1790.

The inspiration for this post–not that it hasn’t always been on my mind in a small, usually resigned, way–was a recent NPR “All Things Considered” segment: How Pirates Of The Caribbean Hijacked America’s Metric System. The segment does note that:

“And you know who was lurking in Caribbean waters in the late 1700s? Pirates. ‘These pirates were British privateers, to be exact,’ says Martin. ‘They were basically water-borne criminals tacitly supported by the British government, and they were tasked with harassing enemy shipping.'”

But the privateers were not tacitly supported by the British government, that is, with implied consent. Rather, they were officially supported, they had explicit consent. They were not pirates, notwithstanding some critics who considered that privateering was in some ways piracy legitimized.

Bad history and click-bait are a common combination these days, although the example above is not by far one of the many egregious examples. Still, it is hard to imagine that the word pirate was used for any reason other than to draw the reader or listener in. Worse, the phrase used in the title is “Pirates of the Caribbean,” conjuring up images of romantic buccaneers, not to mention fantasy pirates like Jack Sparrow.

The correct title of the NPR segment should have been “How Privateers Hijacked America’s Metric System.” But this has much less cachet, and is far less likely to get someone to click on the published article and read it, or tune in later to listen. The title is actually a bit doubly misleading: did the capture of a metric weight really keep the new US from considering the metric system? Or was it, as the segment does note it might have been, just a missed opportunity?

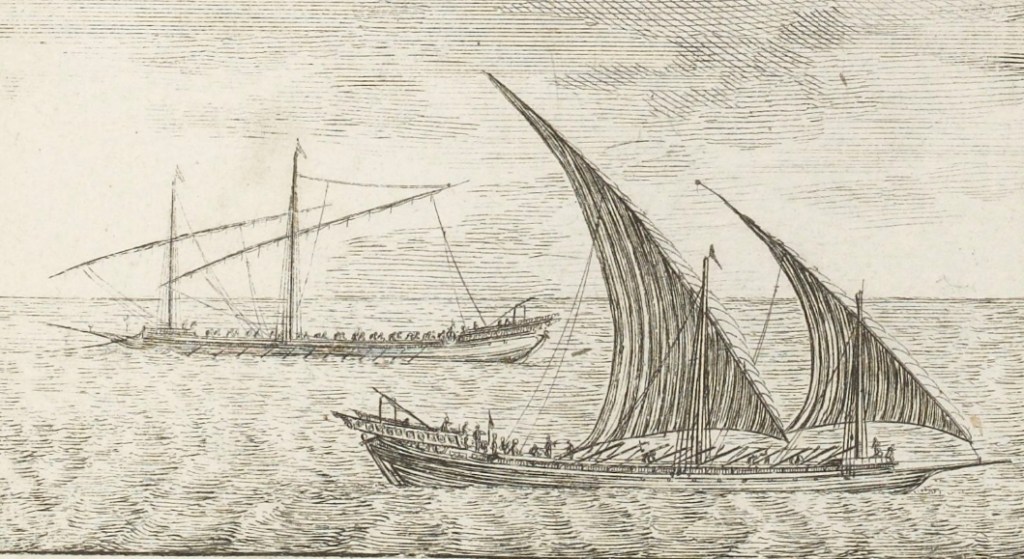

The capture of the lesser Manila galleon, the Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación y Desengaño, in 1709 by the Duke, an English privateer commanded by Woodes Rogers. From the French edition of Woodes Rogers’s description of the voyage. Voyage autour du monde, commencè en 1708 & fini en 1711 (Amsterdam: Chez la veuve de Paul Marret, 1716). Image downloaded from the John Carter Brown LUNA library.

I emailed All Things Considered on this minor matter several days ago. I haven’t heard back, even though I noted my several works on the subject of piracy and privateering. Perhaps the editors found the word click-bait offensive, or the fact that I pointed out that pretty much the same article ran in The Washington Post this past September on Talk Like a Pirate Day.

I’m not singling out NPR, this is just the most recent example I have at hand. I like NPR and have been a listener off and on for decades (mostly depending on how often I’m in my Jeep). But facts are facts, and when they’re imposters it doesn’t matter who the offender is–the offense needs to be pointed out.

The difference might be a non-issue with an educated audience, one that understands the difference between pirate and privateer. But today too many people are getting their education, such as it is, from click-bait articles on social media–articles that are ultimately misleading.

While this may seem to be nothing more than quibbling, it remains vital for the sake of truth to get facts straight. And this includes word definitions because they’re the primary means of conveying factual meaning, aka facts. We’re overwhelmed today not only with obvious liars and subtle liars, but with a large segment of society who excuse loose meaning and interpretation as a means of getting attention. It’s not only ideologues and Mammon’s imps who play fast and loose with the truth anymore, but every know-nothing and know-a-little know-it-all considers his or her wrong-headed opinion to be equal to that of the knowledgeable, facts be damned. And the disease is spreading to mainstream educated society: the Internet is making everyone lazy. How to stop this? By using facts to point out errors, misconceptions, and outright falsehoods.

For the privateer, definitions and facts made all the difference: it’s what kept him from being hanged as a pirate.

Copyright Benerson Little, January, 2018. First posted January 2, 2018.

Novels with Swordplay: Some Suggestions

Illustration by N. C. Wyeth from “The Duel on the Beach” by Rafael Sabatini, a short story soon published as the novel The Black Swan. The illustration was also used on the dust jacket of the first US edition of the novel. (Ladies Home Journal, September 1931.)

For your perusal, a list of a handful of swashbuckling historical novels–pirates, musketeers, various spadassins and bretteurs–with engaging swordplay, even if not always entirely accurate in its depiction. If you’re reading any of my blog posts, chances are you have friends who might enjoy reading some of these books, thus my suggestion as Christmas, Hanukkah, or other gifts this holiday season.

Three caveats are in order: all of the following are favorites of mine, all are set in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and all are not “all” in the sense that the list, even narrowed strictly to my favorites, is quite incomplete. Without doubt I’ll add to it every holiday season. And maybe one day a list of swashbuckling films, another of table and board games, maybe even of video games too…

Upon reflection, perhaps a fourth caveat is in order as well: simply enjoy the stories and their swordplay for what they are. Don’t be too critical, especially of the latter. Except for the case of the reader who is an experienced fencer with a strong understanding of period fencing terms and technique (far more rare than you might think), complex historical fencing scenes cannot be written simply and just as simply understood. Nor can technique and actions in general be explained sufficiently for the neophyte to understand, at least not if the writer wishes to keep the action flowing. The writer must strike a middle ground, one that won’t lose the tempo and thus the reader. This is not so easily done.

Victor Hugo–Hugo to most of us, an adopted Norwegian forest stray–with a pair of late nineteenth century French foils with Solingen blades, and a Hungarian mask made in Budapest, dating to the 1930s. Because cats and swords. Or cats and swords and books.

It’s possible the Moby Dick technique would work–explain and teach prior to the event–but it’s just as likely that many readers would shun this, unfortunately. For what it’s worth, Moby Dick is by far my favorite novel and I consider it the greatest ever written. It is not, however, a book for readers who cannot step momentarily away from the narrative. As I’ve discovered after the publication of two of my books in which narrative history is interspersed with analysis and explanation, there are quite a few such readers, some of whom become plaintively irate and simultaneously–and often amusingly–confessional of more than a degree of ignorance when the narrative is interrupted for any reason. To sample this sort of reader’s mindset, just read a few of the negative reviews of Moby Dick on Amazon–not those by obvious trolls but those by apparently sincere reviewers. Put plainly, using Moby Dick as a template for swordplay scenes would probably be distracting in most swashbuckling novels.

Cover and frontispiece illustration by N. C. Wyeth for the first and early US editions of Rafael Sabatini’s Captain Blood: His Odyssey.

In regard to acquiring any of these enjoyable titles, note that some are out of print except perhaps as overly-priced modern print-on-demand editions. Even for those still in print, I highly recommend purchasing earlier copies from used or antiquarian dealers–there are plenty of highly affordable copies, just look around for them. Abebooks is a great place to start, but only if you have no local independent used or antiquarian bookstores available to try first. And these days, alas, there might not be any…

Why an older edition? Because the scent of an old book helps set the period atmosphere. Add a comfortable chair, a sword or two on the wall, a fireplace in a reading room or a fire pit on the beach nearby, and, if you’re of age to drink, perhaps some rum, Madeira, or sherry-sack on a side table, and you’re ready to go. Or Scotch, especially a peaty single malt distilled near the seaside, it will evoke the atmosphere of Sir Walter Scot’s The Pirate. Scotch always works.

So just sit back and let the writer carry you along. Don’t forget to imagine the ring of steel on steel and the sharp smell of ozone after an exceptionally sharp beat or parry. And if you really enjoy scenes with swordplay, there’s no reason you can’t further your education by taking up fencing, whatever your age or physical ability. If you’d rather begin first by reading about swordplay, you can start here with Fencing Books For Swordsmen & Swordswomen. And if you’re interested in how swashbuckling novels come to be–romance, swordplay, and all–read Ruth Heredia’s outstanding two volume Romantic Prince, details below.

Captain Blood: His Odyssey by Rafael Sabatini

Better known by its short title, Captain Blood, I list this first even though there’s really no significant description of swordplay, not even during the duel that is one of the best parts, of many, in the 1935 film version starring Errol Flynn. You must imagine the sword combat, yet in no way does it detract from this great swashbuckling romance that has inspired readers and writers worldwide, not to mention two major film versions (1924 and 1935). It is truly a modern classic. If you really want to judge the quality of the prose, read a few passages out loud: they’re wonderfully lyrical and evocative.

Photoplay edition from 1935, with Errol Flynn as Captain Blood on the cover. Although technically a photoplay edition, the only film images are to be found on the end papers. A nearly identical dust jacket was included with a non-photoplay edition at roughly the same time, the only difference being that the three small lines of film production text are missing.

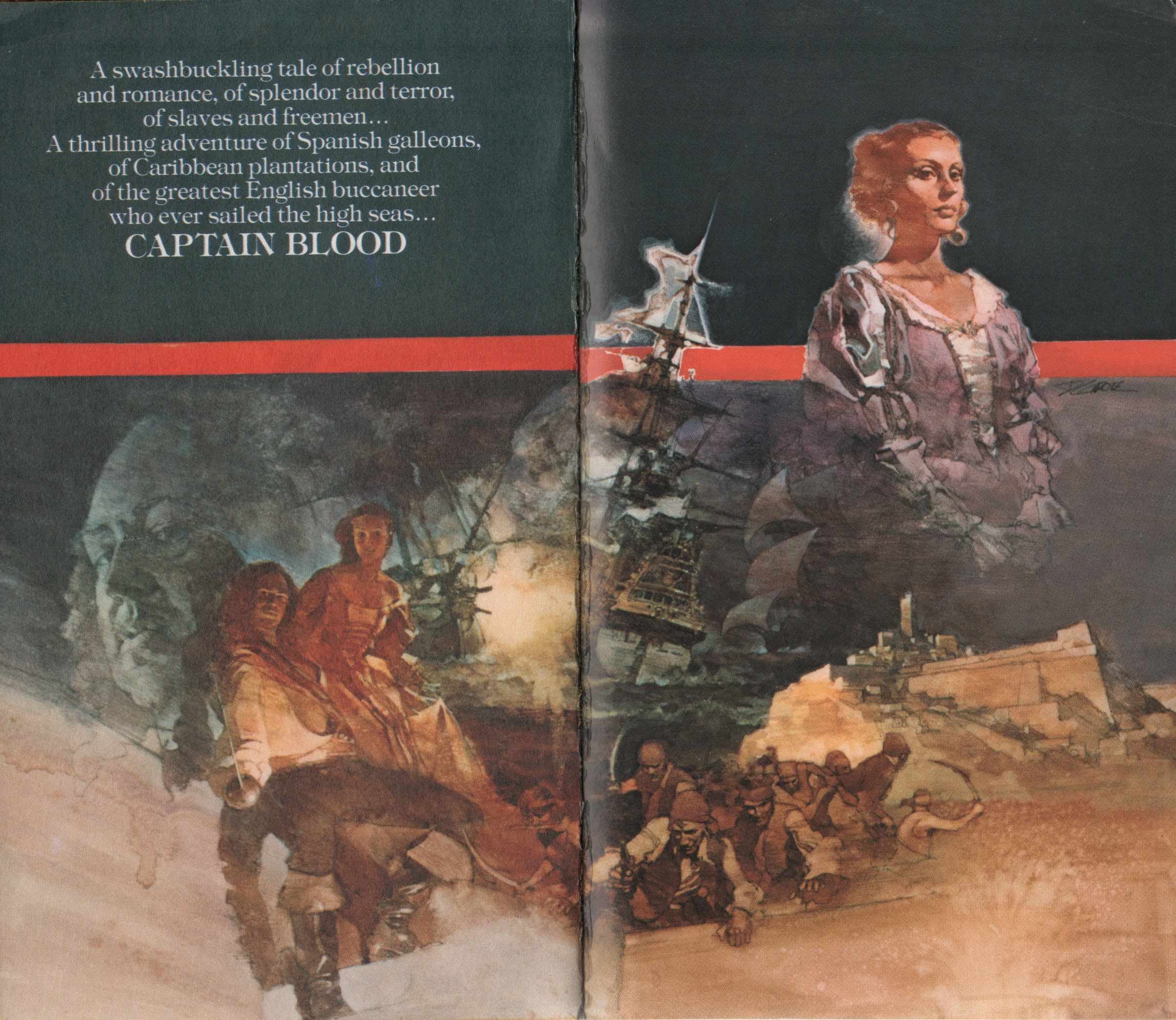

Wonderful artwork from a 1976 US paperback edition of Captain Blood.

Captain Blood Returns by Rafael Sabatini

If it’s a description of swordplay in a tale of Captain Blood, you’ll have to settle for the “Love Story of Jeremy Pitt” in Captain Blood Returns, also known in UK editions as the Chronicles of Captain Blood. Great Captain Blood fare, follow up it with The Fortunes of Captain Blood.

Dust jacket for the first US edition. Artwork by Dean Cornwell.

Endpapers in the first US edition of Captain Blood Returns, artwork by Dean Cornwell.

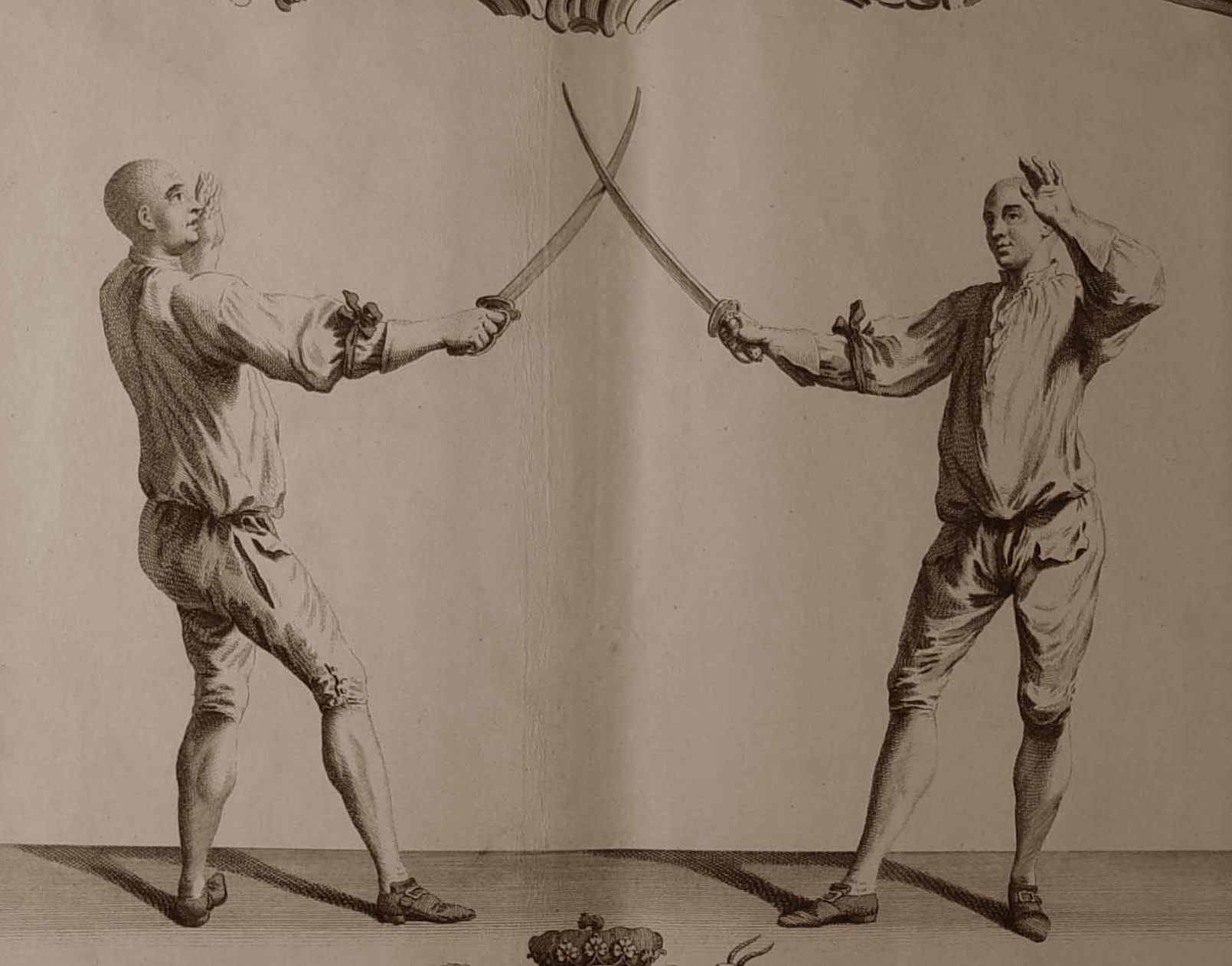

The Black Swan by Rafael Sabatini

One of the greatest of swashbucklers whose plot leads, line after line, to a dueling climax. The 1942 film of the same name, starring Tyrone Power and Maureen O’Hara, doesn’t do the book justice, not to mention takes great liberties with both plot and character.

Dust jacket, first and early US editions. Art by N. C. Wyeth.

Front cover of dust jacket of first UK edition (Hutchinson).

Fortune’s Fool by Rafael Sabatini

An embittered former Cromwellian officer reassessing his life during the early days of the Restoration–and proper use of the unarmed hand in a sword fight too!

Frontispiece by Aiden L. Ripley to early US editions of Fortune’s Fool.

Venetian Masque by Rafael Sabatini

A novel evoking many of the elements of my Hungarian fencing masters’ own history: spies, duels, intrigue, war, revolution, narrow escapes, and above all, courage. Plus Venice!

“With delicate precision he calculated the moment at which to turn and face them. He chose to do it standing on the lowest step of the bridge, a position which would give him a slight command of them when they charged. As he spun round, he drew his sword with one hand whilst with the other he swept the cloak from his shoulders. He knew exactly what he was going to do. They should find that a gentleman who had been through all the hazards that had lain for him between Quiberon and Savenay did not fall an easy prey to a couple of bully swordsmen…”

Illustration from “Hearts and Swords” in Liberty Magazine, 1934. The story would become the novel Venetian Masque. The illustration has been copied from the John Falter collection at the official State of Nebraska history website. Rather sloppily, in both instances in which Rafael Sabatini is referenced, his name is spelled Sabitini. Even the State of Nebraska must surely have fact checkers and copy editors.

Scaramouche by Rafael Sabatini

“He was born with the gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad.” Add a sword and you have Scaramouche.

To my mind, a tie with The Black Swan in regard to a novel built around swordplay, and far superior in its scope. Easily has the best–most evocative, that is–description of a fencing salle, hands down.

To Have and To Hold by Mary Johnston

Listed here primarily as representative of the genre at the time (the late nineteenth century) and because it influenced Rafael Sabatini, the novel has most of the classic clichés of the genre, including the duel for command of a pirate ship, something that never actually happened. A gentleman swordsman, pirates, Native Americans, a damsel incognita in distress… The duel takes place, as best as I can tell, on Fisherman’s Island off Cape Charles, Virginia.

Frontispiece by Howard Pyle.

Dust jacket from the 1931 US edition. Illustration by Frank Schoonover, a student of Howard Pyle. The painting is an obvious homage to Pyle’s painting for the original edition.

Adam Penfeather, Buccaneer by Jeffery Farnol

The prequel to the following two novels, you may either love or hate the style in which it’s and the rest are written, the dialogue in particular. Even if you don’t much care for the style–I don’t much–the series are worth reading anyway for the adventure and swordplay, often including sword-armed women in disguise. Farnol will never come close to replacing Sabatini to me, but this doesn’t stop me from enjoying Farnol’s swashbucklers. And at least Farnol’s dialogue doesn’t sound like, to paraphrase a friend of mine, suburbanites chatting inanely at a PTA meeting–a problem with much dialogue in modern historical fiction and television drama.

As for swordplay, Farnol often takes the evocative approach, providing broad strokes to give a sense of the action without providing detail which might confuse non-fencers:

“Once more the swords rang together and, joined thus, whirled in flashing arcs, parted to clash in slithering flurry, their flickering points darting, now in the high line, now in the low, until Adam’s blade seemed to waver from this line, flashing wide, but in that same instant he stepped nimbly aside, and as Sir Benjamin passed in the expected lunge Adam smote him lightly across broad back with the flat of his blade.”

Non-fencing authors take note of the critical vocabulary for swordplay scenes: rang, flashing, slithering, flickering, darting, flashing…

Dust jacket for the first US edition. The first UK edition has a boat instead…

Black Bartlemy’s Treasure by Jeffery Farnol

Great swashbuckling fare, the first part of a two novel series.

Easily one of the most evocative dustjackets on any pirate or swashbuckling novel.

Martin Conisby’s Vengeance by Jeffery Farnol

This quote alone sells this sequel to Black Bartlemy’s Treasure: “So-ho, fool!” cried she, brandishing her weapon. “You have a sword, I mind—go fetch it and I will teach ye punto riverso, the stoccato, the imbrocato, and let you some o’ your sluggish, English blood. Go fetch the sword, I bid ye.”

The Pyrates by George MacDonald Fraser

Enjoyable parody of swashbuckling pirate novels and films, much influenced by the works of Rafael Sabatini and Jeffery Farnol. Fraser, an author himself of wonderful swashbuckling adventure, was a great fan of Sabatini.

The Princess Bride by William Goldman

Requires no description. The swordplay, like that in The Pirates above, is affectionate parody, and much more detailed than in the film.

25th edition, with map endpapers of course!

Nicely illustrated recent edition.

Rob Roy by Sir Walter Scott

Excellent if mostly, if not entirely, historically inaccurate tale of Rob Roy MacGregor told through the eyes of a visiting Englishman. It has a couple of excellent descriptions of swordplay, ranging from a duel with smallswords to action with Highland broadswords.

Le Petit Parisien ou Le Bossu by Paul Féval père

I’m going to pass on Alexandre Dumas for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that I’ll eventually devote an entire blog to him. If, however, you feel he should be represented here, The Three Musketeers series is where to begin, but you must read the entire series of novels. Be aware that many such series are actually abridged. For a slightly different Dumas take on the swashbuckler, try Georges (an exception to the seventeenth and eighteenth century rule, an almost autobiographical novel in its focus on race and prejudice) or The Women’s War (or The War of Women, in French La Guerre des Femmes). Both are favorites of mine.

Instead, I’ll suggest a great swashbuckler by one of Dumas’ contemporaries. Le Petit Parisien ou Le Bossu is a true roman de cape et d’épée (swashbuckling novel) of revenge from the which the line, “Si tu ne viens pas à Lagardère, Lagardère ira à toi!” (“If you will not come to Lagardère, Lagardère will come to you!”), has passed into French proverb. The novel has been made into film at least nine times, plus into a couple of television versions as well as several stage versions. Unfortunately, I’m aware of only one English translation, and it is excessively–an understatement–abridged. Alexandre Dumas, Paul Féval, Rafael Sabatini are the trinity who truly established the swashbuckler as a significant literary genre.

Bill advertising Le Petit Parisien ou Le Bossu by Paul Féval, 1865. ( Bibliothèque Nationale de France.)

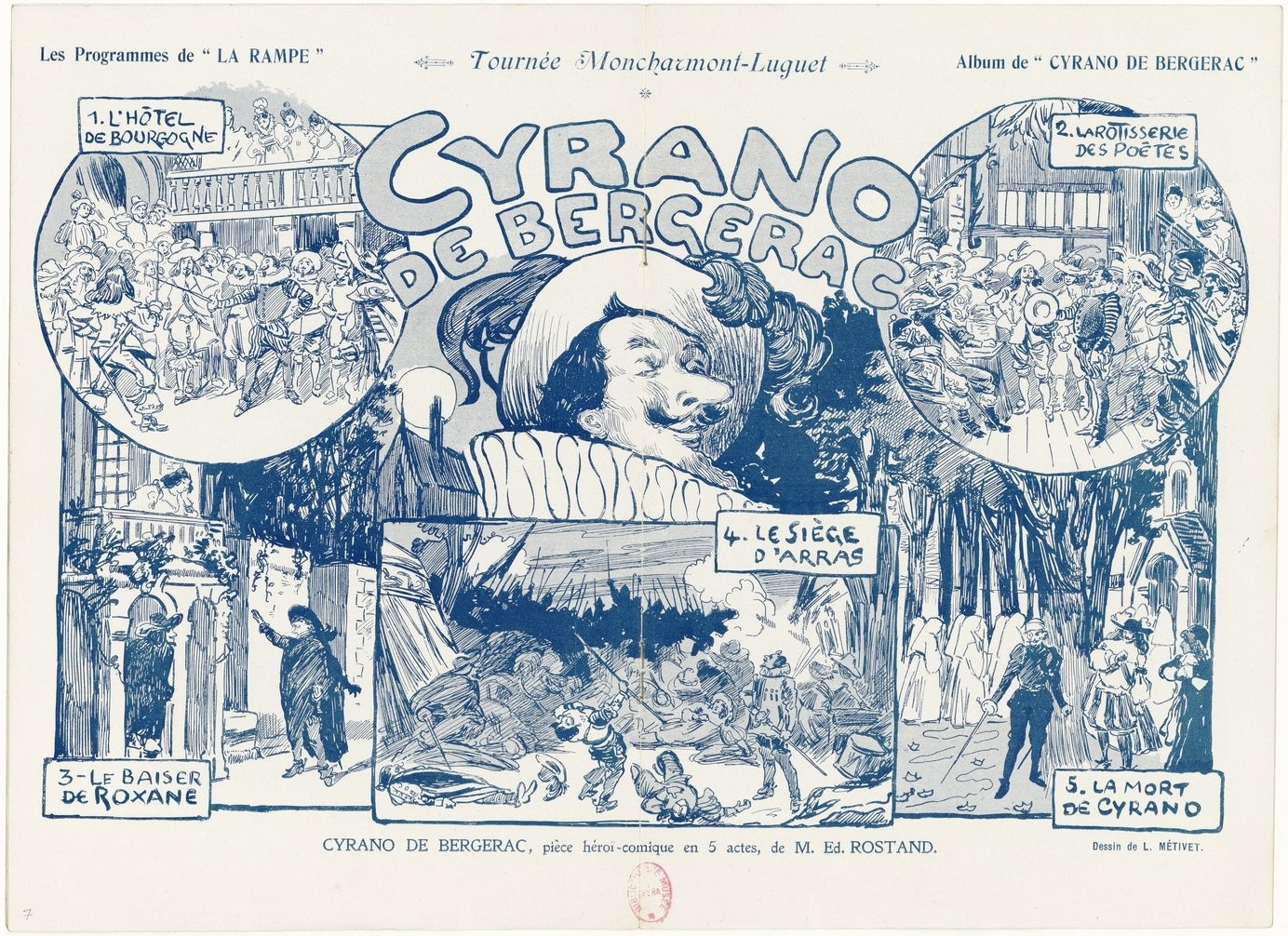

Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand

Not a novel, but mandatory reading nonetheless, with one of the two greatest stage duels ever written, the other being that in Hamlet. Wonderful drama, philosophy in action, and sword adventure, including a duel fought to impromptu verse. Like Captain Blood, it is one of the truly inspirational swashbucklers. To be read at least every few years, and seen on stage whenever available. There are several excellent film versions as well.

Theater program, 1898. (Bibliothèque Nationale de France.)

The Years Between &c by Paul Féval fils & “M. Lassez”

Two series of novels of the imagined adventures of the d’Artagnan of Alexandre Dumas and the Cyrano of Edmond Rostand, filling the twenty years between The Three Musketeers and Twenty Years After in the first, and immediately following Twenty Years After in the second. The books are filled with the expected enjoyable affrays and other adventures of the genre, including the usual improbable circumstances and coincidences. The first series consists of The Mysterious Cavalier, Martyr to the Queen, The Secret of the Bastille, and The Heir of Buckingham, published in English in four volumes. The second includes State Secret, The Escape of the Man in the Iron Mask, and The Wedding of Cyrano, published in English in two volumes as Comrades at Arms and Salute to Cyrano.

Comrades at Arms dust jacket of the US and Canada edition (New York and Toronto: Longmans Green and Co, 1930).

The Devil in Velvet by John Dickson Carr

Fully enjoyable read about a modern history professor who travels to the seventeenth century via a bargain with the devil. The professor discovers that his modern swordplay is superior to that of the seventeenth century–a wonderful idea for a novel but otherwise flawed in reality. At best, if the professor were a “modern” epee fencer, there might be parity. But who cares? After all, who can travel back in time anyway except in the imagination? If you’re a fencer well-versed in historical fencing versus modern (again, not as many as you might think, including some who believe they are), suspend your disbelief. And if you’re not, just enjoy the novel for what it is.

Wonderful endpapers!

Most Secret by John Dickson Carr

Pure genre by the famous mystery writer, this time entirely set in the seventeenth century. Cavaliers, spies, and a damsel in distress!

Dust jacket, Most Secret (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1964).

The Alatriste Novels by Arturo Pérez-Reverte