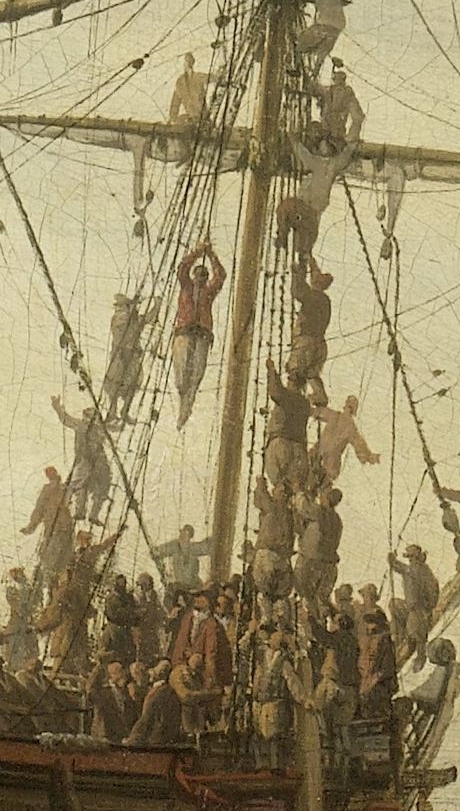

The Keelhauling of the Ship’s Surgeon of Admiral Jan van Nes. Lieve Pietersz Verschuier. 1660 – 1686. Note the enormous crowd gathered for the punishment. (Rijksmuseum.)

As is the case with much pirate history, a great deal of it is wrong, often either anachronistic or culturally mis-associated, or not specifically associated with piracy per se, but with the maritime in general. And so it is with keelhauling, a Dutch practice at first, to which the French and a few other nations later added their small marks.

But keelhauling had little to do with piracy, but this hasn’t stopped it from being including in discussions about pirates and piracy, nor included in pirate fiction and film, most notably and recently in the fourth season of Black Sails. (Full disclosure: I was the historical consultant to Black Sails for all four seasons.)

The original Dutch practice, as described in “A Relation of Two Several Voyages Made into the East-Indies” by Christopher Frick and Christopher Schewitzer, 1700:

“He that strikes an Officer, or Master of the Ship, is without hopes of pardon to be thrown into the Sea fasten’d by a Rope, with which he is thrown in on one side of the Ship, and drawn up again on the other, and so three times together he is drawn round the Keel of the Ship, in the doing of which, if they should chance not to allow Rope enough to let him sink below the Keel, the Malefactor might have his brains knockt out. This Punishment is called Keel-halen, which may be call’d in English “Keel-drawing.” But the Provost hath this Priviledge more than the other, that if any one strikes him on Shoar, he forfeits his hand, if on Board, then he is certainly Keel-draw’d.”

There are several notations of keelhauling and other punishments in the journal of Dutch Admiral Maarten Harpertszoon Tromp in 1639. Typically the keelhauled seaman was drawn three times beneath the ship, apparently not too tightly for he was usually whipped on his “wet bum” with a rope’s end afterwards. For lesser offenses, ducking from the yardarm was employed. In some cases, a seaman convicted of serious offenses might be ducked, keelhauled, whipped, lose his wages, and be discharged. In the case of infirmity due to age or illness, the physical punishments might be stayed, and the seaman discharged instead.

Detail of the victim, from the painting above. The keelhauling line has been rove through a block at the end of the mainyard, and would be similarly rigged on the opposite side. (Rijksmuseum.)

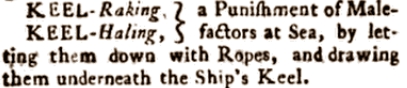

From An Universal Etymological English Dictionary, edited by Nathan Bailey, 1765.

A mid-1850s century French version, described by a former midshipman in the British navy and published in Onward magazine, November 1869, was conducted slightly differently:

The writer continues with a description of what he witnessed:

Terrible indeed!

N. B. Spanish Keelhauling

I’ve also seen one reference to the Spanish using keelhauling: Gemelli-Careri, describing his voyage aboard the Manila galleon in 1697, notes that he heard tell of a passenger, during the senas ceremony, being made to “facendogli passere sopra il Vascello,” from which event he died. The period English translation gives this as keelhauling, although sopra means over, not under. So, while it might be keelhauling, it might also be ducking, which is more likely given the ceremony of senas, or signs of land. Ducking might be inconvenient, even frightening to some, but wasn’t usually fatal. Keelhauling often was.

N. B. Keelhauling’s Ancient Origin?

A number of web articles and books, both popular and scholarly, note that keelhauling is of ancient origin. However, this is probably not the case. Scholar Henry A. Ormerod in Piracy in the Ancient World (1924) claims that an image on an ancient Greek vase shows keelhauling, and he has reproduced the image as the frontispiece to his book. However, I see nothing in the image to suggest keelhauling per se. Instead, it appears to depict some form of water torture of prisoners who had their hands tied and were thrown overboard, perhaps pulling them back to the surface as they begin to drown. However, the image does not appear to show keelhauling as we define it—the dragging of a victim beneath the vessel from one side to another. In fact, the victims have only one line attached: keelhauling generally requires two.

Similarly, some scholars and other writers note that the Lex Rhodia of 800 BCE describes keelhauling as a punishment for piracy, but there are actually only a few short paragraphs of the Lex Rhodia that still survive and they don’t discuss punishment for piracy, so I’m not sure where this idea originated. It may be a misreading of Ormerod, who suggests that it may have described punishments for piracy. The only line that refers to piracy is in regard to responsibility for paying the ransom of a ship to pirates. This is a common problem in history: the repetition of misinformation or incomplete information as fact.

My thanks to writer Sylvia Tyburski, whose questions to me on the subject caused me to review the facts on the purportedly ancient origin of keelhauling! I’ll post a link to her article as soon as it’s available.

Copyright Benerson Little 2017. Last updated July 10, 2018.